The words we cannot say, the Language of Hate, the Violence that Follows…

It’s a word we don’t say in public anymore.

Nigger.

We say “the n word”–as if that euphemism doesn’t translate into the actual racial epithet in everyone’s head. But we make that transliteration because we are supposed to be moving away from our racist past as a nation. We say “the n word” because to say anything else is just too shocking in 2015, too much of a reminder of all the ugliness and hate and incomparable violence associated with that word.

The word nigger.

I remember the first time I heard that word as if it were yesterday, even though I was a very young child. I remember it, because I had never heard it before, and yet I knew by the way it was said to me, the way it was spat at me, when my elementary school classmate called me a “nigger lover,” and said my parents were “nigger lovers,” that it wasn’t a good thing.

But I was not prepared for what would happen when I went home that day and asked my mother what it meant.

She slapped me.

The first time I heard that word was not the last. But it taught me how much violence went with that word. So much violence that my own mother–the civil rights worker, the woman who with my father helped organize the Philadelphia to Philadelphia Project between my northern city and rural Mississippi in the era of Bull Connor and the march on Selma–my own mother wanted to slap that word out of her daughter’s mouth and into the dirt where it belonged.

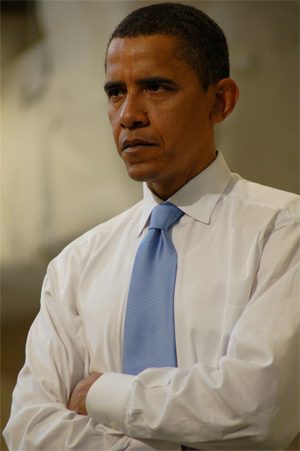

When President Obama said the word in an interview with Marc Maron for his podcast WTF [ http://potus.wtfpod.com/ ], he said it in the context of a discussion of racism in America. A discussion that happened less than 48 hours after America was reminded that we are nowhere near a post-racial America, despite our biracial president–the son of a white woman from Kansas and a black man from Kenya.

A discussion necessitated by the brutal, execution-style murders of six women and three men as they prayed in their church, their historic black church.

President Obama said,

That word. He said it. Out loud. A word he had written in his memoirs. A word he had been called. A word he was intimately familiar with. A word he has tried to protect his family from–his wife, his young daughters.

A word that won’t go away.

A word that was at the heart of those murders in Charleston.

A word that has simmered at the edges of American discourse for my entire life.

A word that has riven America for generations.

A word that has Othered black Americans since our first president and 12 others who owned slaves, eight of them, including Thomas Jefferson, author of the Declaration of Independence, while in office.

Much of white America was upset with the President for saying the word out loud. White reporters appeared shocked–from CNN to FOX, which referred to the President as the “rapper in chief.”

Obama saying the word so many on the Right have covertly and not-so-covertly called him throughout his presidency was, according to many on social media as well as several news commentators, “disrespecting the office.” One white man tweeted me that he was offended and found it “uncouth.”

Yet at least three white presidents have used that word–and not in the context of a discussion of race in America: Harry S. Truman, who desegregated the military with an Executive Order in 1948, Lyndon B .Johnson, who signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law and Richard Nixon, who issued an Executive order creating the Office of Minority Business Enterprise in the Department of Commerce and issued an Executive Order calling on Federal agencies to apply Equal Opportunity policies to every aspect of personnel policies and practices.

Publically they acted one way, privately, quite differently. All three used the n word in common parlance while in office, according to aides, friends, biographers.

Yet as Obama also told Maron,

Still, as every marginalized American knows, the words we cannot say are still used. And all the venom that goes with that loaded language remains, its poison still there, still doing damage.

Obama ended the Maron interview succinctly, asserting that “the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, discrimination” exists in institutions and casts “a long shadow and that’s still part of our DNA that’s passed on.”

The language of marginalization always begins with the slurs–the words that separate us, that Other us, that make us less than. Slowly we remove them from common parlance, but they are still said in private.

Those of us in marginalized groups talk about reclaiming words, but can they ever truly be reclaimed? I used to use “dyke” and “queer” all the time in my writing, and then I realized with the former I was giving haters permission to use that word as the slur it had always been and with the latter I was erasing lesbians.

So I stopped.

The problem of the language of marginalization, as any of us who has been on the receiving end of a slur knows, is that we cannot reclaim language that has a sordid history of hate and violence. We can, in our own living rooms and in spaces that are wholly ours, use those words among ourselves–our own oppressed group.

Perhaps. But Out There we cannot. Out There it allows others–often the very people who have historically been our oppressors–to appropriate the language of our oppression and use it against us.

Because they want to. They haven’t moved past the hate. They’ve just euphemized it.

And that is the real reason so many white people are upset with President Obama for saying the n word. Just as they have been upset in the past with black entertainers using that word or the accepted public variant, niggah.

Because they want to use it, too. Because they think there is some special privilege going on when President Obama or Chris Rock uses that word and they can’t.

And that is why we are nowhere near a post-racial America.

Because even thinking that you could say that word as a white person is so far back in 1950s Jim Crow America, that it merely underscores the importance of what Obama said to Maron. That saying “the n word” is a facade–because many people, too many people, are still thinking the actual word and aching to say it.

We hear all the time that these are “just words.” As little children we are taught that “sticks and stones can break my bones, but names can never hurt me.”

Except words do hurt. Words carry their own violence, their own weight of history. And they are used as weapons, often in combination with physical violence. The man who murdered Sakia Gunn because she dared to spurn his advances called her a “dyke” as he stabbed her. In July 2012, three masked men broke into a lesbian’s house in Lincoln, Nebraska, bound her with zip ties, carved the word “dyke” into her stomach, cut her all over her body, and set her house on fire with gasoline.

They also spray painted the walls with anti-gay slurs. At the 2014 San Francisco Pride event, two lesbians were attacked after a group of men hurled anti-gay slurs at them, Last fall the man who instigated a mob attack on Chicagoan Quintas Lockett and her girlfriend was convicted of a hate crime.

Both women were attacked verbally before they were attacked physically. In March, Roisin Prendergast and her girlfriend Ciara Murphy were verbally and physically abused by a group of men who first attacked them with anti-gay slurs, then beat them until Murphy was unconscious.

Towleroad reprinted Preendergast’s Facebook comments after the women were released from the hospital:

“I know our bruises will heal, I know we will be okay, but this is not something I am going to let go. Watching someone you love getting hurt while you yourself are getting hurt is not something anyone should ever have to endure straight or gay. T

his to me was a hate crime. I am finished crying, today starts the first of many actions which will be taken to get justice.”

Every day in schools, in the workplace, on the streets, on social media these words are tossed around like so much confetti. Historical footage of the de-segregation of the schools in Little Rock, Arkansas shows ordinary men and women–mothers of children–yelling the n word at young black children. Children.

Because those words separate us. They make us less than human.

That ugly scene in Little Rock was decades ago and the n word has been taken out of public discourse. But racism is still rife–we saw it in Charleston. We see the Confederate flag, the flag of slavery and treason and racism still flying in a dozen states.

Other words–homophobic, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, a slew of ethnic slurs–have not been taken out of use. They are still commonplace. Hate crimes against lesbians and gay men are on the rise.

Many missed the point President Obama was making in his bold interview with Marc Maron. Many tried to scold the President–the biracial president whose mother was white and father was black and whose wife is black and who has born the hurt and anger of that word and for himself and his family–for using a word we have all grown up hearing at one time or another.

The language of Othering is still there, even if we don’t say the words, don’t use the language. The invective, the vitriol, the simmering violence just beneath these words remains. We have to stop Othering, marginalizing, demeaning and diminishing.

There was a smugness in the shock white newscasters evinced, as if they had caught President Obama doing something wrong.

But what is wrong is that these slurs still exist, and that when one of the most egregious is taken out of circulation, people are still itching to grab it back and toss it around some more.

I will never forget the day my mother slapped me for repeating what had been said to me–hurled at me like a fist. Even though I was a small child, I understood that day some measure of that word’s power.

We can’t take back the language of hate.

All we can do is try somehow to heal the wounds those words and all they stand for have created.