Chantal Akerman Changes Narrative Cinema with Her Depictions of Women’s Lives.

Chantal Akerman, Belgian filmmaker, film theorist and lesbian feminist iconographer of women’s lives, died suddenly on Oct. 5, reportedly a suicide. She was 65. Akerman directed more than 40 films and television projects and at the time of her death had been attending and speaking at screenings of her most recent film, No Home Movie.

The tragic end to the brilliant filmmaker’s long career came less than a year after the death of her mother, Natalia, a Holocaust survivor of the Auschwitz concentration camp. Akerman had filmed her mother’s final days in her Brussels apartment. That video essay, No Home Movie, is part of an upcoming retrospective of Akerman’s work in London in late October where Akerman was also to teach master classes in film.

Akerman, who suffered from bipolar disorder which she discussed in several interviews, notably “The Pajama Interview” with French film theorist Nicole Brenez, had been hospitalized for depression and was released just 10 days prior to her death. She was due to be in New York on Oct. 7 for a series of screenings of No Home Movie at the New York Film Festival. She was found dead late on the night of Oct. 5.

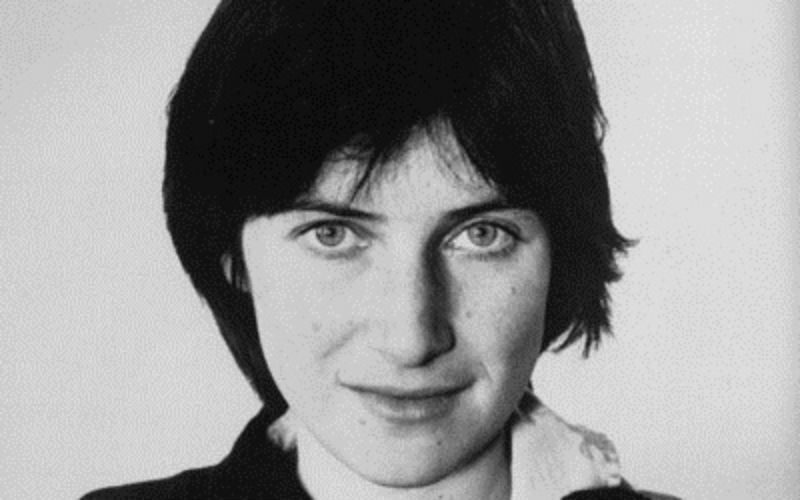

Festival director Kent Jones posted a statement about Akerman on the NYFF website, and shared a glimpse of her persona, noting that she was “direct, tough and emotionally extravagant. She was small in stature, but she commanded a room with her fatigued stance, her grand and sometimes wicked smile, her wild rough-grained voice and her eyes. The eyes had it. I’ve rarely looked into a pair of eyes so bewitching.”

Akerman stunned the film world from a young age and has been compared with film icons Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard, who she said repeatedly had turned her into a filmmaker. Numerous filmmakers have cited her as an influence, including queer filmmakers Gus Van Sant, Sally Potter and Todd Haynes.

Her most recent narrative film was Almayer’s Folly, based on the Joseph Conrad novel, which she filmed in Cambodia. Other recent work includes The Captive, Over There, South and From the East. She also taught at City College in New York, but was not teaching this semester.

In 1975 at the age of 25, Akerman changed the face of independent filmmaking by making the gaze definitively female with her groundbreaking feature film, Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles.

As Nicola Mazzanti, director of the Belgian Film Archive told the New York Times, “There are filmmakers who are good, filmmakers who are great, filmmakers who are in film history. And then there are a few filmmakers who change film history.”

Akerman was one of those and Jeanne Dielman was the film that created the change.

Nearly three and a half hours long, the film follows the title character, a widow with a young son, as she goes through her quotidian days, which include prostitution to support herself and her son. The film is bleakly interior and feels like real time to the viewer as the focus on Jeanne’s (played brilliantly by French actress Delphine Seyrig) highly structured and obsessively regimented behaviors begin to be seen as a stop gap against her breaking into a million pieces.

The film depicts three days in Jeanne’s life and the slow deterioration of that life to a climactic and utterly unforeseen yet deeply female climax. [The entire film can be viewed here on Hulu: www.hulu.com/watch/235471 ]

The film was made with an almost wholly female crew and Akerman told Camera Obscura magazine,

When Seyrig died at 58 of cancer in 1990, Akerman said the actress had created a character in Jeann Dielman that was uniquely feminist. Of Seyrig herself she said what might have been said of Akerman herself, “The French film establishment never forgave her for her outspokenness. If she had not been so beautiful, so aristocratic, it might not have been so bad. But the incongruity between their fantasy of her and what she was–a total feminist activist to the end of her life–they couldn’t tolerate that. She was as much a force in our lives as she was on the screen and that’s something very rare.”

Akerman also said she didn’t fully understand her own character until years after the film was made, after she herself had had “a mental crisis.”

She said, “While I was writing it, I didn’t understand Jeanne Dielman. I didn’t understand it until many years later: it was also a film on lost Jewish rituals, not just about an obsessive woman. If she’s so obsessive, it’s to avoid leaving an hour open to anxiety. And when that extra hour arrives, all her anxiety surfaces.”

Jeanne Dielman was not released in the U.S. until 1983, but when it was, it received rave critical reviews. The New York Times called Jeanne Dielman the “first masterpiece of the feminine in the history of the cinema.” The Village Voice placed the film at 19 in its “100 Best Films of the 20th Century.” In The New Yorker, Richard Brody wrote, “It is no overstatement to say that she made one of the most original and audacious films in the history of cinema.”

Audacious is a word often used to describe Akerman who made her first film at 18. It signaled her as a film prodigy. In the 13 minute black & white short “Saute Ma Ville” (“Blow Up My City”), Akerman dances around her kitchen to a soundtrack of singing and humming. At the film’s end, she puts her head down on the stove’s burners. Fade to black. The room explodes. Fin.

When I interviewed her in 1996, for my book Film Fatales: Independent Women Directors (written with Judith M. Redding, Seal Press), Akerman spoke about her early work with a kind of fondness, saying that she had made “Saute Ma Ville” to get the attention of…someone. “I thought if I make a short film I could show it to anyone, and it will help me.”

When she spoke of making that film at only 18 she was matter of fact about it, but noted that she had to do it, to get her work noticed. And that she had been thinking about it for a couple of years, since she was 15 and had first gone to the cinema with her girlfriend to see Jean-Luc Godard’s now-classic film, Pierre le Fou and was transformed. Up until that point, she said, movies were for “eating ices” and “holding hands with your girlfriend or boyfriend.”

But after seeing that film she knew she wanted to make movies.

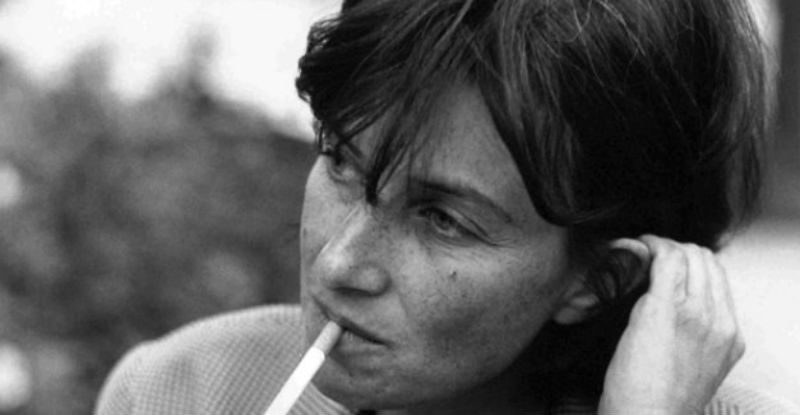

Akerman’s voice then was soft, vulnerable, her English heavily accented. She was, in a word, captivating. And somehow quite different from her films. Where the films are often filled with a calculated restraint, Akerman herself was intensely animated, her hands moving, her cigarette punctuating her comments, her face incredibly mobile, her words repeatedly accented with puffs of air or a dramatic eye roll.

It’s almost impossible to imagine that woman, that vibrant, barely contained force, not just gone, but gone at her own hand. That is the power depression has over even the fullest of lives. And the many layers of female despair and elation and their counterpoints were always themes in her work.

Perhaps the films were in fact a clear extension of Akerman’s self–perhaps that feeling of desolation that some of her female characters exhibit was in fact a feeling she herself knew well, yet managed to keep hidden in much the way Jeanne Dielman keeps her roiling emotions in check–until she doesn’t.

The juxtaposition of emotions as well as the juxtaposition of seemingly ordinary spaces with extraordinary conflict became Akerman’s signature. Her 1976 film Je Tu Il Elle (I You He She) was groundbreaking not just for its female-driven narrative, but for its overt lesbian sex scenes.

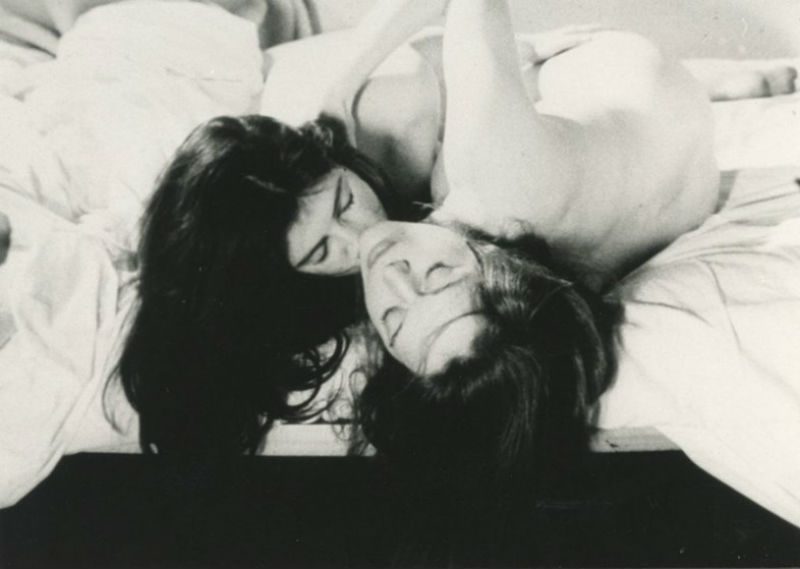

Like Jeanne Dielman, the film has a seemingly simple plot: Julie, a young woman recovering from a break up spends days on end alone in a room. She paints the room, moves her furniture around, writes and re-writes the breakup letter, eats powdered sugar. She leaves her room for something to eat and gets picked up by a truck driver. They go to eat and he talks. She then goes to the house of her former lover who says she cannot stay. She says she is hungry and her lover feeds her and allows her to stay the night. They have sex, wrestling together in the bed.

Of the film’s title, Akerman said, “‘Je’ is a girl voluntarily locked up in a room. ‘Tu’ is the script. ‘Il’ is a lorry driver. ‘Elle’ is the girlfriend.”

Akerman played Julie, Claire Wauthion, the French actress with whom she was involved in real life, played the girl.

What is surprising in both Jeanne Dielman and Je Tu Il Elle is the overt sexuality in each film, but seen not from the male (pornographic) gaze, but from the perspective of the women characters in the films and from Akerman herself. The sex has unexpected effects on the women–with stunning consequences.

In 1974 when Akerman made Je Tu Il Elle, there were no lesbian sex scenes in mainstream filmmaking. There were no scenes of raw female sexuality. The exposition of this by Akerman was new and different, feminist, and, for some, shocking.

Akerman addressed taboo subjects in her films, most notably female sexuality. The betrayal scene in the final act of “Jeanne Dielman” is one of the most dramatic in feminist cinema. But the scene itself is taboo on several levels–for it’s sexuality and for its violence. And yet we perfectly understand it. Every woman in the audience understands it.

Just as every woman, lesbian or not, will understand the sexual/romantic triptych in “Je Tu Il Elle.”

The complexities of female sexuality pervade all of Akerman’s films, even fluffy fare like A Couch in New York, starring Oscar winners William Hurt and Juliette Binoche. The film was her one foray into totally mainstream filmmaking.

In her review of Akerman’s 1978 film Les Rendez Vous d’Anna, New York Times critic Janet Maslin wrote of the film’s central character, who is in and out of bed with women and traveling from place to place gleaning information from those around her while never quite connecting, “Most of the tales told to Anna cut right to the bone, to the very simplest level of despair, and yet the film’s tone is too detached to seem bleak. If anything, the mood is mysteriously playful at times, as in a sweet, knowing sequence that shows an uncharacteristically light-hearted Anna singing a little song to one of her lovers. ‘A little sunshine can be so bright that it hurts,’ goes the refrain.”

These complexities were the foundation of Akerman’s work. Yet that character of Anna was uniquely representative of Akerman herself–traveling from country to country, place to place, touching so many with her work, yet still held in her own traumatized and traumatizing past, as evidenced in her final film, the documentary with her mother.

Despite being an out lesbian throughout her life, Akerman resisted having her work shown in LGBT festivals, just as she did Jewish film festivals, because she did not want to be “ghettoized” as a filmmaker. She said she didn’t want people viewing her films with preconceptions. In her interview with Brenez, she explains this, while discussing the work of the great Robert Bresson. “I came to Bresson late, when I was around 25, after the Nouvelle Vague. Bresson is also a great materialist. The priest’s ear in ‘Diary of a Country Priest’: in my whole life I’ve never seen such a great ear, I stared at it endlessly. This is why ‘Catholic filmmaker’, ‘Jewish filmmaker’, ‘woman filmmaker’, ‘gay filmmaker’ – all these labels have to be thrown away, that’s not where things really happen.”

Perhaps. For me, knowing Akerman was a lesbian filmmaker was important–necessary, even. Knowing those lesbian scenes in her films came from life, not gratuitous sensationalism was essential. Did that make the scenes more real? I don’t know. But they made her, Akerman, more real, more accessible.

Akerman’s films were filled with women characters of deep intensity–women who were exultant or agonized, suffering or resilient, sexually combative or sexually willing. The atmosphere of her films always felt real and honest, contemplative but never exploitative. She was someone who you felt you knew from her work. And yet, she never saw herself as someone to be known by her multiplicity of fans.

Akerman told Brenez, “Really, it’s always better not to meet ‘the creators’. Whenever anyone tells me, I love your work, I’d like to meet you, I always say: it’s better not to. I’ll disappoint you.”

Akerman did not disappoint. Her films in all their variations do not disappoint. But that Akerman has left us so soon and with so many stories left to be told is beyond a disappointment. It is an actual tragedy.

Akerman’s films are available at the Criterion Collection.