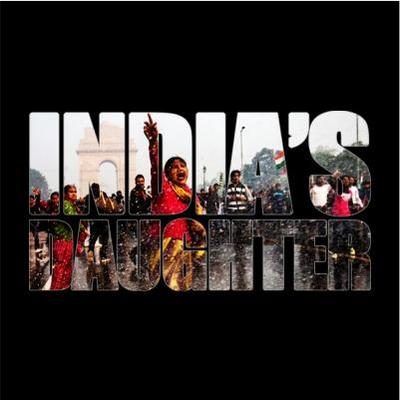

Delhi Bus Drivera’s Words Spark Outrage as Documentary Is Banned

*Trigger Warning (Sexual Assault Content)*

On March 4, India’s Parliament, the Rajya Sabha, moved to ban the BBC documentary “India’s Daughter,” by award-winning filmmaker Leslee Udwin.

India’s Home Minister Rajnath Singh released a statement that a restraining order had been obtained against the screening of “India’s Daughter.” The documentary is focused on the barbaric December 2012 Delhi gang-rape and beating of a 23-year-old medical student as she road the bus home after seeing a film with her boyfriend. Both were beaten–the man into unconsciousness–with an iron rod, which was also used to sodomize the victim.

At the end of the rape and sodomizing of the victim by all six men, her intestines were pulled out through her cervix and she was thrown out of the moving bus onto the roadway. She died 13 days later in a hospital in Singapore where she had been airlifted due to the severity of her injuries.

Udwin’s film documents how the rape further galvanized women who had already been working against India’s rape epidemic where government statistics show 93 rapes are reported each day, but as in all countries, under-reporting is widespread. Delhi, the site of the gang rape, has the most rapes. Unlike in many countries in the West, rape is on the rise, not the decline, in India, which some advocates for rape victims say is because of deeply entrenched views about the role of women in Indian society.

Yet rape–not even this rape–was not the topic of Minister Singh’s concern. Rather the minister said the government would investigate why Udwin was given permission to interview one of the rapists on death row in the case. (Such permissions are granted to filmmakers in the U.S. on a regular basis, most recently on Feb. 27 to ABC News for Diane Sawyer’s documentary on women in prison. She interviewed two women who are on death row for murder.)

Singh said, “When I heard about the documentary I was hurt. Under no circumstances should this be telecast. So we got a restraining order from the court.”

The outrage over Udwin’s film stems not from the rape, but from the comments made by the man she interviewed, Mukesh Singh (no relation to the Minister), who was the bus driver and one of the rapists. Outrage also has targeted Udwin herself, who has been branded a “white savior” who unfairly depicts Indian men in her film.

In a March 3 interview in The Guardian, Udwin discusses her shock at the attitudes held by Indian men toward women.

There is no question that Mukesh Singh’s comments are shocking. In the film he says, “A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy. Boy and girl are not equal.” Singh also says “Housework and housekeeping is for girls, not roaming in discos and bars at night doing wrong things, wearing wrong clothes. About 20 per cent of girls are good.”

Singh refers to the rape as an “accident” and says if the victim had just been quiet and submitted, it would all have been over and everyone could have gone home.

“When being raped, she shouldn’t fight back. She should just be silent and allow the rape. Then they’d have dropped her off after ‘doing her,’ and only hit the boy,” he told Udwin’s team. He added, “The death penalty will make things even more dangerous for girls. Now when they rape, they won’t leave the girl like we did. They will kill her.”

The comments are as extreme as the rape itself.

The problem is that the Delhi rape, brutal as it was, and the comments of Singh, utterly lacking in empathy as they may be, are far from singular.

As “India’s Daughter” was being released, in the U.S. the documentary “The Hunting Ground,” about the epidemic of rape on college campuses, was also released–to little media attention.

The reports of victims/survivors in “The Hunting Ground” are indicative of just how horrific these rapes–all committed by one student upon another–can be. One rape activist,.a lesbian, who I spoke with in 2013 was involved with the film and has been part of the Title IX efforts to force colleges to address campus rapes as rape rather than disagreements between students. She described her rape to me in stomach-churning detail. Her injuries were so severe–fisted by the rapist who was wearing a watch at the time–that she was unable to use tampons for over a year. Yet her college treated her as if she were just trying to get out of going to class.

If this is the way college administrators, who are supposed to be acting in loco parentis to their student body, speak to a savagely attacked teenaged college student at a prestigious U.S. university, why are we so shocked at a bus driver in India talking about women as if they were mere receptacles? Why even did Udwin need to leave her native U.K. to do the film when similar comments could be found on my own Twitter feed in response to my agitating that convicted rapist and U.K. soccer star Ched Evans not be hired back when he was released two years early from his jail sentence? Between the rape threats to the U.K. woman, Jean Hatchet, who organized the petition against Evans, as well as to me and other women involved in the activism, Udwin would have had documentary evidence to rival Singh’s comments.

I am one of America’s millions of rape victim/survivors. I was raped outside my own home in broad daylight on a sunny September afternoon, dragged from my front garden to a neighbor’s yard, my arms pinned behind my back. I was brutally beaten, choked, bitten (there were bite marks around both of my nipples, the scars of which took more than a year to fade), orally sodomized, raped. The only reason my face remained undamaged (although my lip was split open) was because the rapist told me he wanted to “look at your pretty face” until he was finished with me. Then, he told me, he was going to choke me to death and smash my face in with a rock he held over my head at various points in the attack.

Incidents like what happened to me or to my college friend do not make the newspapers like the horrifying attack in Delhi, but are they less terrible? India may have a “rape problem” and South Africa may have a “corrective rape problem”with regard to lesbians, as I have written about here before, but the reality is, there is no such thing as a civilized versus uncivilized rape.

All rape is brutal and dehumanizing. If we are “lucky,” we aren’t killed like the Delhi victim. If we are “lucky,” rape threats online, which some of us receive nearly every day and which Twitter and Facebook shrug off as free speech or some other misogynist cant, don’t materialize into actual rape.

But women–all women, everywhere–have had the fear of rape instilled in them from childhood. And one in four of us has already been raped by a family member or close family friend or teacher before we turn 18.

The fact is, documentarians like Udwin don’t need to leave their own neighborhoods to report on the pandemic horror of rape that threatens all women, everywhere, regardless of her age, race, class, sexual orientation (a lesbian was gang-raped outside San Francisco in 2009 and the men who attacked her were finally convicted last year), gender identity (rape of trans women sex workers is common, as I reported in my award-winning series, Victims of the Night, for PGN last year), ability (rape of disabled women is nearly 20 times as frequent as that of non-disabled women).

.jpg)

Babies are raped in South Africa because it is believed that virgin girls will cure men of HIV/AIDS.

But babies are raped in the West as well. Just last week Gary Glitter was convicted and sentenced to 16 years in prison for the rape of several children, including one as young as eight. In 2013, Lostprophets singer Ian Watkins was convicted and sentenced to 29 years for the attempted rape of his girlfriend’s one-year-old baby.

But those two cases–Glitter’s and Watkins’–only made the news because those men are famous. What about all the men who aren’t? The man who raped me had already raped several other women in my neighborhood before me–his particular modus operandi was known to the police from previous victims.

Rape is the most prevalent violent crime in the West. It is also a tool of conflict as I reported here for Curve

And it is a pandemic in our universities as “The Hunting Ground” details and in our military as the Oscar-winning documentarians of “The Hunting Ground” reported in their previous film, “The Invisible War.” America has a rape problem as I reported here and so does the UK and EU and pretty much everywhere.

So as horrified as we are by the blatant statements of Mukesh Singh and the barbaric treatment of his victim, we must remember that men we know are making similar statements online every day, anonymously and that famous men like Bill Cosby, once called “America’s dad” and less famous men like your parish priest or the music teacher at your kid’s school or the guy who drove you home after babysitting when you were in high school have all been rapists, too. But it will never be the topic of a documentary. Or maybe even reach the news.

And that is the problem. Until we acknowledge that rape isn’t something that happens “over there,” but something that happens here, now, right where you are, men will continue to rape with impunity and the law will continue to be on their side, not ours.