What the gender-bending magic and mystery of Prince meant to lesbians.

It was surreal: I was dozing in a hospital bed, when a news bulletin broke into the daytime programming I’d fallen asleep watching. Prince—the brilliant, sexy and most of all seemingly eternal superstar—was dead. Was I dreaming? Hallucinating?

Only four months after the sudden death of David Bowie in January, another superstar who changed the way we see ourselves is gone.

The world turned purple as news of his death spread. Landmarks all over the country and beyond shone with purple, from the Eiffel Tower to the Empire State Building to the Seattle Space Needle. A spontaneous dance party erupted in the streets of Minneapolis. We knew it was true. We just couldn’t believe it.

Prince, born Prince Rogers Nelson on June 7, 1958, was a musical genius. We’ve been blessed with a few of these in our collective lifetime, men and women whose innovative musical talent re-imagined music and style and the very idea of what music can do. Bowie was one, certainly.

Michael Jackson. Sir Paul McCartney. Beyoncé is certainly becoming one as the brilliance of “Formation” and now Lemonade have proven.

These singer/songwriter/musicians have taught us something about ourselves through their music, through their lives, through the risks they took/take.

Prince has been with us so long that it seems like he was always a superstar. But his blackness held him back in the MTV era when black artists were still marginalized.

When Prince opened for the Rolling Stones in 1981, he was pelted with vegetables and fruit and booed off the stage to shouts of “faggot” and the N-word. More than 30 years later he would say on an episode of New Girl in which he guest starred, “Anything beautiful is worth getting hurt for. You know who said that? Me.”

Since his death on April 21, everyone has tried to claim a piece of Prince—but he was first and foremost a black man. Something he never wanted anyone to forget. That 1981 concert must have felt like a brand on his soul—he never stopped promoting black artists.

It was revealed after his death that he was a major philanthropist for arts groups—but they all had to promise not to reveal he was a benefactor. Of his philanthropy he told an interviewer “It keeps the bad away.”

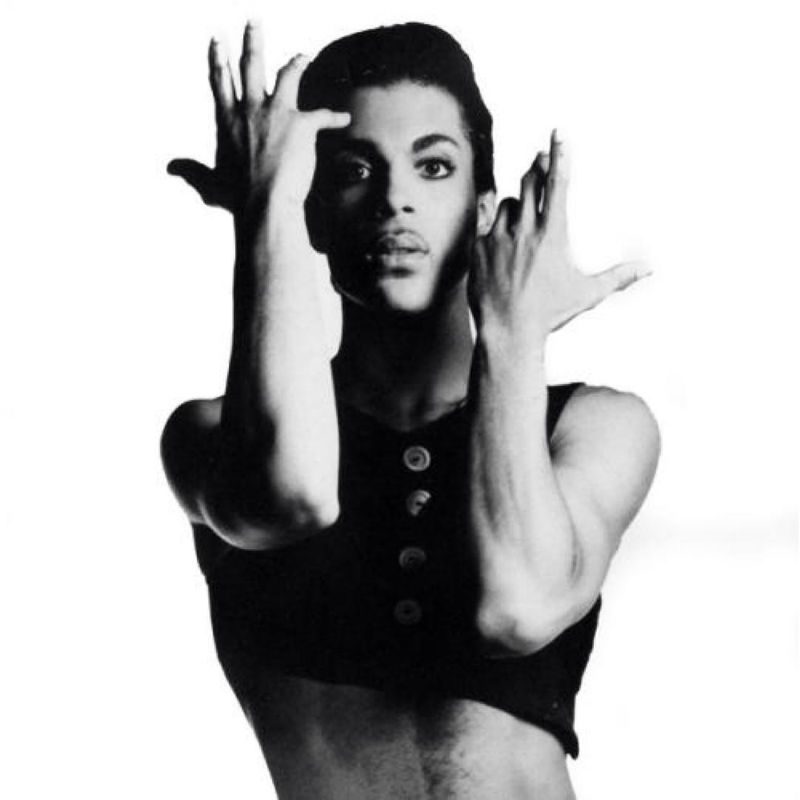

Prince was a risk-taker. An iconoclast. A shapeshifter. Prince bent gender till it screamed for mercy and then screamed for more. In his song “I Would Die 4 U” he sang, “I’m not a woman/I’m not a man/I’m something that you’ll never understand.”

And we didn’t really understand—just like when Prince changed his name to an unpronounceable symbol we didn’t quite get it. But did we even need to? Wasn’t Prince giving us permission to do and be anything? It seemed so.

Prince wasn’t gay, although he appeared gay-friendly. (It was shocking to discover last year that he opposed gay marriage, something the Washington Post noted again on April 22.) He wasn’t bisexual, though his body language always seemed to embrace both men and women.

Prince taught men that they didn’t need toxic masculinity to be sexy as hell. Eyeliner, high heels, lacy Victorian shirts—and yet just so…manly with his effortless James Dean style and his dancer’s body and his bedroom eyes.

It was a dichotomy that made everyone who walked that gender-non-conforming line breathe easier. Because Prince was a superstar and deeply religious and didn’t smoke, drink, take drugs or swear. And yet—look at him.

We could be like him. We could defy those rigid stereotypes that hurt so deeply.

Prince’s lyrics often disrupted gender and left us confused or embraced or both. “I Want to Be Your Lover” was one of his sexiest songs, but check the lyrics:

“If I was your girlfriend/ Would U let me wash your hair? Could I make U breakfast sometime? Well then, could we just hang out? I mean, could we go to a movie and cry together? ‘Cause 2 me baby, that would be so fine. But I, I said I want 2 be, all of the things U are 2 me.”

And raise your hand if you own the Lovesexy album with Prince naked in a bed of Georgia O’Keeffe-style flowers, posed like Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, disarmingly covering a breast and shielding his genitalia with a demurely raised leg. It was 1988, George H. W. Bush had just become president and, whoa.

There was Prince in all his magical glory. We hadn’t seen a male superstar naked since John and Yoko a decade earlier. And they were anything but sexy in that demonstration.

Deconstructing what these incidents meant decades later isn’t simple. And yet those of us coming of age in those days knew what Prince was doing (like Bowie before him) would smash something that would make it easier for us to breathe.

Prince loved women with a passion we usually associate with super-macho men. He cherished women. Held them up. Put the spotlight on them. He was a huge promoter of women’s talent and had women in his bands from the very beginning.

He was a mentor to many, not just the women he was involved with like Vanity, Mayte Garcia and his drummer and former partner Sheila E. In the early ’80s Prince premiered Vanity 6, an all-girl band with his then girlfriend Vanity (Denise Matthews) at the helm. Later, when Vanity left the group, Apollonia would take her place.

The list of women whose careers he helped launch or expand included Sheena Easton, The Bangles, Chaka Khan. Oscar-nominated actress Kristin Scott Thomas got her start in Prince’s music video “Under the Cherry Moon.”

He wrote songs for Madonna, Cyndi Lauper, Nona Hendryx, Patti LaBelle, Paula Abdul, Sinead O’Connor, Mavis Staples and so many others. He asked Stevie Nicks to be part of Purple Rain.

Prince had been influenced by his parents—his mother, Mattie Shaw, was a jazz singer and a victim of domestic violence at the hands of Prince’s father, John Lewis Nelson, a jazz pianist and songwriter. Prince detailed some of that abuse in the film Purple Rain and in his most compelling song, “When Doves Cry.”

They influenced him musically and personally. Friends of Prince said his gentleness toward women was in direct response to the abuse he witnessed as a child.

“When Doves Cry” wasn’t like anything else 30 years ago when Prince wrote it—men didn’t write lyrics like this:

How can you just leave me standing?

Alone in a world that’s so cold? (So cold)

Maybe I’m just too demanding

Maybe I’m just like my father too bold

Maybe you’re just like my mother

She’s never satisfied (She’s never satisfied)

Why do we scream at each other

This is what it sounds like

When doves cry

Sheila E spoke with ET April 25 about the small memorial service held for Prince—only 20 people—and said, the service was “somber and sad.” The musician said listening to Prince’s music without him was hard.

“What was challenging yesterday was listening to his music at a very low soft volume and the room very low in lights and everyone just taking a moment, just sitting there, kind of going, ‘Wow,’ [in] disbelief.”

The music was what mesmerized us. The music was so transgressive. Those lyrics. That guitar. The voice.

My favorite Prince song was “Kiss,” which I danced to so many times in the clubs. Like Bowie’s “Fame,” “Kiss” had a raw sexiness that wasn’t like anything else.

Don’t have to be rich

To be my girl

Don’t have to be cool

To rule my world

Ain’t no particular sign I’m more compatible with

I just want your extra time and your

Kiss

Oh

We’d be singing those lyrics as the music blared and we sweated on the dance floor. The opening bars, the guitar. Prince was the background to our lives in the ’80s–that many-octave voice and that sinewy, magical, androgynous singer/guitarist/dancer/performer.

The music video directed by Rebecca Blake spotlights Prince as a dancer. Prince appears in a half shirt and leather jacket. He takes the shirt off, accompanied by a veiled dancer (Monique Manning) who is wearing black lingerie and aviator sunglasses while Prince’s guitarist Wendy Melvoin, from his band Revolution, sits playing guitar.

Prince is mesmerizing in the video and the music is steamy. At a time when MTV wasn’t showcasing black performers, “Kiss” became a huge hit.

So did Purple Rain. Not just the song, but the film, which became a transgressive cult favorite. Purple Rain has been re-released in theaters nationwide. Prince’s songs—“Purple Rain” at the top of the list—are currently 15 out of the top 20 songs in the country.

As if the last 30 years never happened—you can turn on the radio and hear “Purple Rain” and “Let’s Go Crazy” and “Little Red Corvette” in an endless loop tape of nostalgia.

Sheila E told ET, “When you’re in a place of musically creating and writing, you just do your thing, and you don’t realize how many people you touch. I don’t know that he really knew how he touched almost everyone in this world.”

In “1999,” the party song for the millennium, Prince wrote:

I was dreamin’ when I wrote this

So sue me if I go too fast

But life is just a party

And parties weren’t meant to last

War is all around us

My mind says prepare to fight

So if I gotta die

I’m gonna listen to my body tonight, yeah

Prince taught us to listen to our bodies, to be who we wanted, that we didn’t have to be a man or a woman or fit into a gender box. We could be both or neither, but we could choose. In “Let’s Go Crazy” he told us:

Dearly beloved

We are gathered here today

To get through this thing called life

And if the elevator tries to bring you down

Go crazy, punch a higher floor

Prince took us to a higher floor. And forever made purple synonymous with that journey.