Kitty Genovese: America’s Lost Victim

* Trigger Warning*

[This article contains sexual assault themes.]

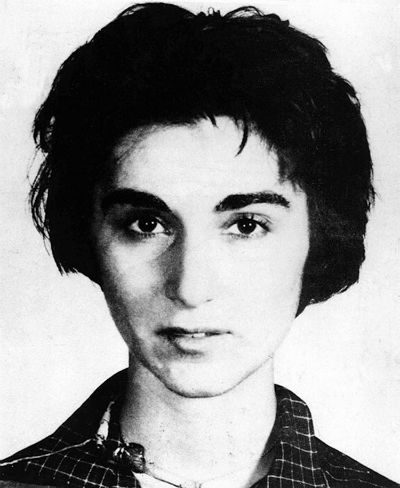

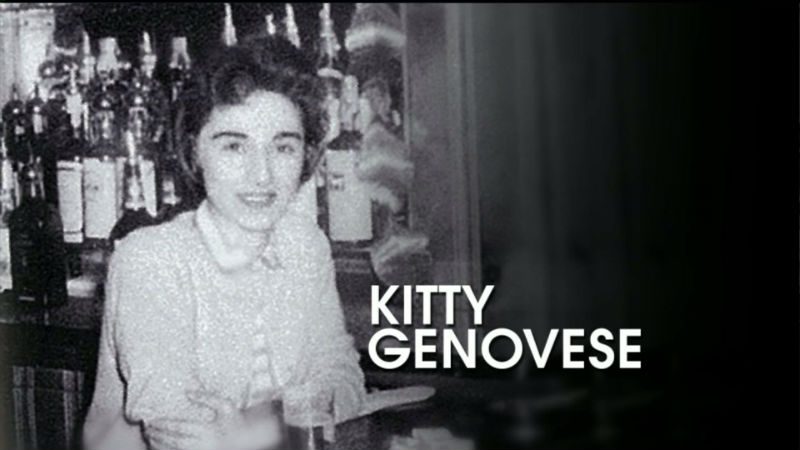

She would be 80 years old this year. She might have lived an extraordinary life or she might have just lived a simple happy one with her lesbian partner and friends. She might have continued to be everyone’s favorite bartender–at 28 she was already a bar manager–or she might have gone on to run her own business.

She might have been a figure at Stonewall, her slender, gamin Italian good-looks on the front lines with other lesbians outside the Stonewall Inn during the days of rage in June 1969 that birthed the modern lesbian and gay civil rights movement.

She might have been home, in her Kew Gardens apartment in Queens, cuddling in front of the TV with her partner, Mary Ann Zielonko, the portrait Mary Ann had painted of her sitting on a park bench with the wind in her hair on a wall nearby. Or she might have been out dancing with Mary Ann, because she loved to dance and she and Mary Ann were going to learn to salsa together.

Except Catherine “Kitty” Genovese would do none of those things.

Genovese would, however, become famous: The most famous murder victim in the history of New York City. A victim whose grisly, violent rape and murder would become the stuff of not just news reports, but also pop psychology and existential philosophy. A victim who, 51 years after the anniversary of her March 13, 1964 murder, still haunts the city and still haunts us, the details of her murder and her life only being revealed now, decades after her killing.

Kitty Genovese was coming home from work on the night of March 13, 1964. It was a Friday. Friday the 13th. The most unlucky of days, according to legend. It certainly was the most unlucky for Genovese.

Winston Moseley, a 29 year old African-American businessman with a wife and two children, had been trolling the neighborhood for a new victim. As he would later testify at trial, between January and Genovese’s murder, he had already raped “four or five” other women, including Annie Mae Johnson, who he had raped and shot after setting her genitals on fire.

That night, Friday the 13th, Moseley was driving through Kew Gardens. He followed Genovese’s red Fiat and when she parked and walked toward her apartment building, he followed her, stabbing her twice in the back.

She screamed, “Oh my God, he stabbed me! Help me!” and one neighbor, Robert Mozer yelled “Leave that girl alone!” from his window. Another man called police and told them there was a girl who’d been hurt.

Moseley ran off and Genovese, now seriously wounded, staggered to her apartment. building. But Moseley caught up with her inside the vestibule. At trial he testified that she screamed, and he stabbed her in the throat. He continued to stab her. He raped her vaginally and orally and also raped her with the knife. The assault took place over 33 minutes. Wounds on Genovese’s hands from the knife indicated she still tried to fight Moseley off. He robbed her of her tips for the night–$49–then left her to die.

On March 27, two weeks after her murder, with her killer in custody after he was arrested for a different crime, Genovese’s murder suddenly became news.

This was the headline on the front page of the New York Times that day:

That was how Genovese became famous–more famous than any of the other 600 people murdered in New York City that year. Or any year. The apparent lack of concern by her many neighbors for the young woman after she was first stabbed, when her life might have been saved, became the stuff of psychological profiling. Genovese’s murder–or rather, the lack of response to it–was cited repeatedly as emblematic of a culture of apathy. A term for this behavior–The Bystander Effect–became not just common parlance, but a psychological phenomenon to be taught and discussed, always in the context of Genovese’s murder.

As Zielonko told NPR in 2014, “I still have a lot of anger toward people because they could have saved her life, I mean, all the steps along the way when he attacked her three times. And then he sexually assaulted her, too, when she was dying. I mean, you look out the window and you see this happening and you don’t help. That’s — how do you live with yourself knowing you didn’t do anything?”

The New York Times story began, ““For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens….Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead..”

That was almost the way it happened, but not quite. Two neighbors called police. One neighbor, Joseph Fink, could have saved Genovese’s life. He had a clear view of the first attack, but ignored her screams. The other, Karl Ross, a friend of Genovese’s, heard the attack but did nothing. It was he who told police, “I didn’t want to get involved.”

When the ambulance arrived, Genovese was being held by another neighbor, Sophia Farrar, the only heroic person in the sordid, tragic story. The last words Genovese heard, were Farrar whispering to her, “Help is coming.”

Genovese died on the way to the hospital.

The New York Times called Genovese’s murder and the response of her neighbors–or the lack thereof– “a frozen moment of dramatic, disturbing social change.”

While Genovese was being brutalized, her partner was upstairs–asleep and oblivious about how her life would be changed forever. The perils and pathos of being a lesbian in 1964 would soon overwhelm her when police came to her door. She would be asked to identify the body of the woman she loved as she lay under a blood-soaked sheet in the Queens Hospital morgue.

For hours Zielonko would be questioned by police, initially the prime suspect in her murder because as lesbians, violence and perversity were presumed in 1964. Months later, at Moseley’s trial, Zielonko would testify as the roommate, the friend, not the spouse.

Kitty Genovese was the love of Mary Ann Zielonko’s life at the time of the murder. Zielonko recounted how they got together to various reporters on the anniversary of Genovese’s death, telling the Chicago Tribune that the two women had lived together in a motel for several weeks until they found that apartment in Kew Gardens.

“We just hit it off,” Zielonko said. “We meshed. I’m very quiet, and she talked a lot. We both had struggles with our sexuality, as did many people back then. We had a quick bond.”

Zielonko said the two had met at a gay bar in Greenwich Village, The Swing Rendezvous, not far from where the Stonewall riots would happen a few years later. Genovese came up to the blonde, model-pretty Zielonko and said, “Don’t I know you from somewhere?”

Zielenko, then-24, fell for Genovese. She said a week after they met she got a note taped to the door of her apartment: “WILL CALL YOU AT THE STREET CORNER PHONE BOOTH AT 7. –KITTY G.”

After March 13, 1964 there would never be another call.

Zielenko was ignored by police, ignored by Genovese’s family at the funeral. For six months after the murder she worked and drank and slept. Then she tried to get on with her life.

But the killing has followed her. She told various news outlets that she tried reaching out to the Genovese family–she thought before Genovese’s murder that Kitty’s mother really liked her. But they never spoke again after the murder. Nor did she ever speak with Genovese’s four siblings. She was left to fend for herself and recover by herself. To this day she has had no contact with any of them, even though she and Kitty would drive up to the Genovese home in Connecticut on weekends.

Genovese’s name is a matter of criminal history–a famous victim. But her life as a lesbian, her days spent with Mary Ann, her nights spent dancing at various gay bars in the Village, that part of her life has been kept hidden, as if it, not her savage killing, was the shame.

Now, decades later, she is known solely for being a victim. But she was so much more. Kitty Genovese was 28 and in love with another woman to whom she was returning home on the night of her murder. She was, by Mary Ann’s account and the accounts of others, a smart, vivacious, fun-loving young woman with plans for herself and Mary Ann.

Kitty Genovese was so much more than her killing. She was one of us. We should not let that be forgotten.