The lesbian appeal of Kristen Stewart arguably began with her first film performances as Patricia Clarkson’s adorable tomboy daughter in Rose Troche’s The Safety of Objects (2001), and as the adorable tomboy daughter of Jodie Foster in Panic Room (2002).

Seeing Stewart at work as a 9-year-old, I was actually reminded of Jodie Foster when she was a child star. Like Foster, Stewart stayed in the business and, also like Foster, grew a show-business shell that both attracted fans and prevented them from getting too close to her. This armor and the ambiguity it created served Stewart during the Twilight juggernaut but kept her from her lesbian fan base. She teased us with outings such as The Runaways, in which she portrayed Joan Jett, but she still seemed somehow unknowable.

It’s only recently that we’ve felt able to claim Stewart as one of our own. The August 2015 issue of Nylon reveals a rapport shared by Stewart and Jett on the set of The Runaways. “Your people are here for you,” Jett would tell Stewart by way of encouragement. “Kristen, pussy to the wood!” she would yell, if her trainee’s guitar performance needed more grit. But when would Kristen come out? “Google me,” she would say. “I’m not hiding.” She was, just in plain sight. She certainly dressed like one of us, and she spent a lot of time with Alicia Cargile. What was her problem? Come out, already!

Stewart resisted. She told Nylon: “I am an actress, man. I live in the fucking ambiguity of this life, and I love it. I don’t feel like it would be true for me to be like, ‘I’m coming out!’ No, I do a job. Until I decide that I’m starting a foundation, or that I have some perspective or opinion that other people should be receiving . . . I don’t. I’m just a kid making movies.”

If that seems evasive, a year later everything had changed. In a Los Angeles Times interview this past July, Stewart declared: “I’ve discovered a way to live my life and not feel like I’m hiding at all. And I think that’s pretty apparent for anyone who cares—not that everyone does. But I think that if you had been tracking it in any way, it’s more apparent that I’m more relaxed than I used to be.” The media had indeed been tracking her intimacies—with Cargile, and with French singer Soko for a few months, then with Cargile again.

Stewart knew that hiding was pointless. In fact, she didn’t seem to care anymore.

Then tabloids reported that Stewart had split from Cargile and was dating St. Vincent. They were allegedly inseparable in New York this fall, where Stewart took St. Vincent to the 54th New York Film Festival, to a sushi dinner, and exploring the city. They were photographed strolling together in the East Village. They were smiling.

Getting Stewart to come out on our terms last year was about as hard as getting her to smile for paparazzi. At only 26 years old and with a net worth of $70 million, Stewart could be forgiven for feeling the pressure to have both privacy and career credibility. But finally she is mastering herself and her power. She’s now dating Stella Maxwell and she seems much more comfortable as she is snapped, quite literally, out and about.

Watching Stewart at the press conferences for the New York Film Festival in early October, where she had three non-mainstream films showing (Certain Women, Personal Shopper, and Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk), I thought there was still a lot of “the kid” about her, but more of the serious artist.

At the press conference for director Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women, she showed off her long legs in shorts topped with a T-shirt and a black blazer, but seemed a little awkward, nervously tapping her maroon and cream oxfords, and occasionally biting at her thumbnail. She answered questions, but her answers were brief, halting, or self-deprecating. She was funny, too, her comments sometimes underscored by wild gesticulating. Stewart was animated by the topic: Certain Women is part of the “good shit” she’s been making recently, working with non-mainstream directors she grew up admiring. “I’m really not precious about it,” she says. “I’ve just gotten super lucky lately.”

Certain Women is a drama built around a quadrant of women who live in a small Montana town.

Stewart plays a young lawyer in a tiny firm who must drive for hours to teach education law to a group of teachers after work. When a female rancher, a Native American, falls for her, Stewart’s character, glad of the company but struggling to get by, is oblivious to the woman’s attentions. In one scene, Stewart eats a hamburger and wipes her mouth with a rolled napkin, the cutlery still inside it. It’s a curious gesture: unpretentious, awkward, just like Stewart herself. Asked why she chose that gesture for her character, she says, “She has no time. I don’t know—there’s stuff on your face, just get it off. She’s so distracted and fucking self-absorbed . . . What do you mean, though?,” Stewart adds, leaning toward the journalist who asked the question, as if she herself might get to learn something more by examining her own choices.

Stewart is not interested in fame or money. Her focus is on artistic process. “I would never draw attention to the distinction between doing a big movie and a small one . . . I guess you could technically draw a distinction, because you have more money to play with,” she tells us. “I mean, naturally, it affects the dynamic a little bit [but] I’ve never approached anything going, ‘Oh, this is bigger now, therefore I’m less entitled to something meaningful.”

Lately, Stewart has deliberately chosen meaningful work, especially independent films in Europe.

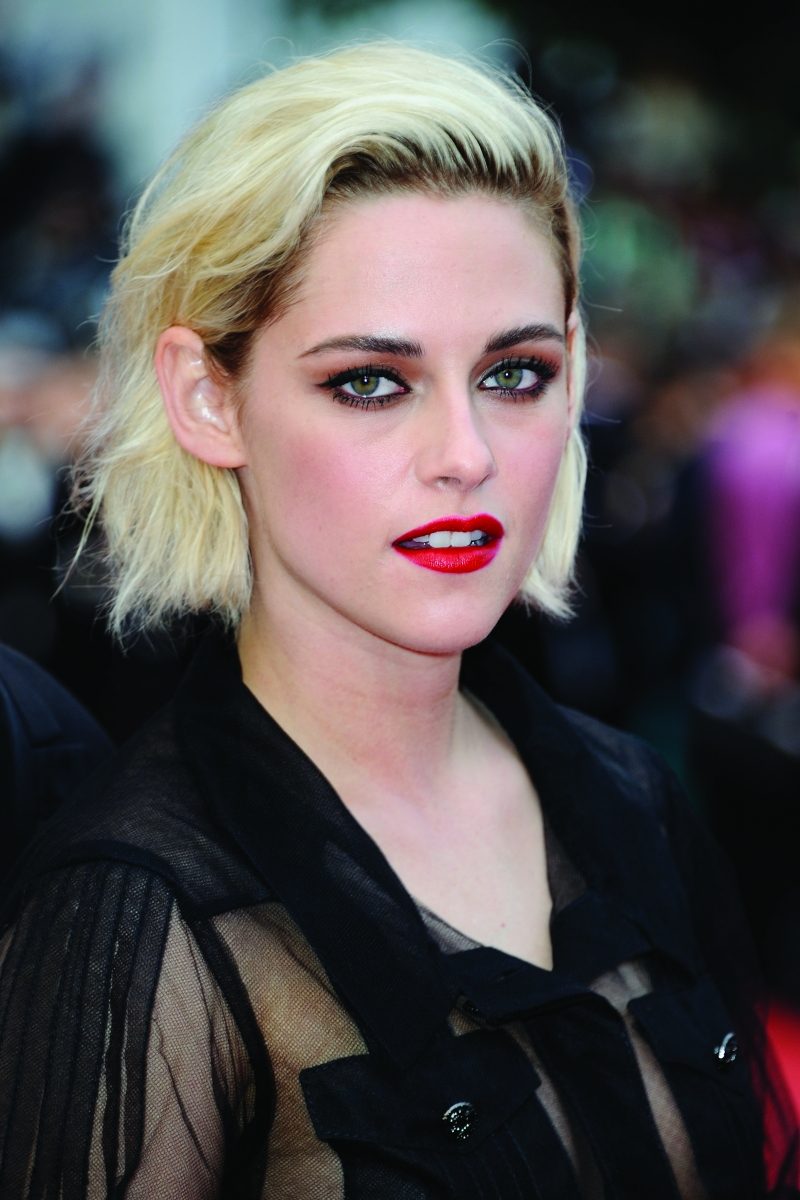

In an interview she did in Cannes to promote her appearance in the Woody Allen film Café Society, Stewart was asked if she enjoyed the world’s most glamorous film festival. “I love how people take film very seriously here. I’ve devoted my life to observing people and studying behavior and wanting to be part of making films. This has been my entire life, really. . . . Usually, when I’m attending a film premiere in Hollywood, I become very nervous in those situations, but here in Cannes I’m much more comfortable and I enjoy my time here so much.”

In the film Clouds of Sils Maria (2014), written and directed by French auteur Olivier Assayas, Stewart plays a nerdy and fastidious personal assistant to a particularly dykey-looking and neurotic Juliette Binoche. Stewart won a César Award (the French Oscar) for her efforts, and so pleased was Assayas that he wrote another role for her, this time as the underpaid but protective “personal shopper” for a famous young actress; Personal Shopper is a genuinely scary multi-genre ghost story about loneliness and the digital age. In the film, Stewart plays Maureen Cartwright, a fraternal twin with the same heart condition that has just killed her brother, Lewis. They shared an oath that the first one of them to die would send the other a sign from the other side. Like her deceased twin, Maureen is an amateur medium. His death gives her the opportunity to test her paranormal skills, but it also opens a Pandora’s box of paranoia and psychic tension, and launches Maureen into an existential crisis about who she is and how much control she has over her life. In Personal Shopper Stewart seems to be a lot like herself: intuitive, tense, testing her limits. She is spiritually and literally naked in the film. If you wish to see a topless Stewart and more, this is where to look, but the exposing scenes aren’t gratuitous.

Speaking at the New York Film Festival press screening of the film, Assayas said that Stewart is “completely spontaneous and physical . . . I think what is extraordinary with Kristen is how smart she is with understanding the most intricate complexities of filmmaking. She brings such incredible pace, rhythm. She recreates the character from the inside, and she does it knowingly, but at the same time she is guided by her body.” It’s really her physicality, he says, that shapes this film. And in particular, it is her physicality portrayed in isolation. Often, she is alone, or alone with technology—a screen or a cell phone text.

Stewart arrived late to the press conference with Assayas, possibly because the night before she had been honored with her own An Evening With… event held by the Film Society of Lincoln Center, which was celebrating her recent “enigmatic roles in complex films“ and her willingness to “challenge herself and her fans.“

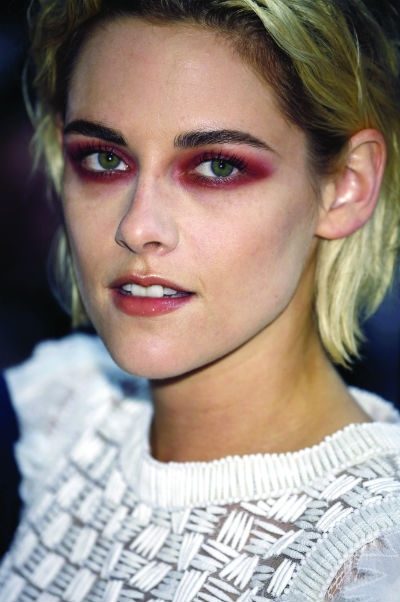

Stewart took to the stage amidst cheers and immediately demonstrated her rapport with her director. She looked tired but gorgeous, fashion-savvy but also serious.

“Some of the sexiest shit I’ve done on screen, I’m alone,” she tells us. “It was like, Oh my god, it’s just such massive disconnection. You’re just fabricating a wonderful reality that’s not real, it’s just perception.”

“It was really up to Kristen within the shot to put the emphasis on this or that,“ says Assayas, “and she dug up from within the character and within the story whatever resonated with her. . . . I think one thing Kristen masters in a way that’s unique is time within a specific shot.” So much so that Stewart became almost a co-creator, in control of the pace of filming, extending the duration of certain shots or scenes. “I was not bored one second. I was always discovering something new that Kristen was bringing . . . It’s very much a combination of Kristen’s work and mine.”

It’s perhaps ironic that Stewart’s physical presence has been harnessed to such commanding effect in a film that is essentially about absence and the power of the things we can’t see. “Nothingness was the start of it,” says Stewart about creating her role, “and it’s like you can’t really always take credit for something that comes through you. It’s fucking weird, but the first time you approach something like that, it’s cool.”

While the film is essentially about Stewart stalking a ghost, the ghost is also stalking her. It’s a parable of 21st-century surveillance, the result of the proliferation of mobile and digital technology. “Yeah, it’s funny because I think Maureen wants to be invisible, and at the same time she wants to be really seen,” says Stewart. “She struggles with that, and I think that’s pretty much everyone right now. Even the most out there people . . . I don’t hide anything. I don’t have any public social-media things that I engage with, but I ultimately want to be seen. It’s weird. We think we have more control over that now than we’ve ever had, because we have it in our hands, but we have none. I don’t know. Like, I have this weird preoccupation with other people, which is so unbelievably distracting . . . it’s so time-consuming. It’s like there are two sides to it: We stalk each other. I stalk people. I get stalked. We all are obsessive, you know what I mean? The whole movie she’s struggling with this identity crisis, because she’s two very separate versions of a person—and that’s not a bad thing, it’s just hard to sort of contend with as a younger person.”

She’s not only describing her character; she’s describing herself, hiding in plain sight, wanting to be, and terrified of being, seen. Ask Stewart a direct question, though, and she’s likely to answer: Does she have a personal shopper?

“I have a stylist, and she’s rad. But I choose my shit. I don’t, like, get dressed by someone. But you know, this isn’t mine,” she says, plucking at her gorgeous tailored tuxedo jacket, which she has paired with mustard plaid ski pants and sky-high black stilettos. “We just borrow this stuff and go, ‘Thanks,’ and then we give it back.”

Does she believe in the paranormal? “It’s that thing of, if that’s real for you, then what the hell else is there? There’s so much that we don’t see that we know to be true. It’s kind of a self-protective reduction to say, ‘Do you believe in ghosts? Have they touched you?’ Well, what else doesn’t touch you, but exists? . . . I don’t know what the fuck energy is—there’s something that doesn’t go away, and whether I’m making that up or I’m actually being left with some residual debris, I feel people fucking intrinsically, you know what I mean? I think it leaves shadows.”

It’s easy to think that mega-famous film stars are so privileged that they’re above fear and impervious to danger, but there’s something about Stewart (and her liberal use of F-bombs) that indicates vulnerability. Personal Shopper is, she has said, “the most isolating and lonely movie I’ve ever made,” but she was drawn to the story because she felt she had much in common with Maureen. “When I was younger, I suffered a lot from anxiety and doubts. And, like Maureen, I know that feeling of intense isolation that comes from being stuck in your own head.”

The shoot, which involved 16-hour days, was emotionally and physically exhausting. “But that’s what makes the process of acting exciting for me. It may seem strange, but I feel more alive and fulfilled when I’m suffering and reaching the point of exhaustion. . . . It’s been my experience that all those times which while you’re going through them are so devastating—are actually the experiences that are going to make you stronger and more aware. Whenever I’ve gone through traumatic moments, I’ve always come out afterward feeling more alive and confident. You have this sense that you can finally be happy and feel fulfilled, the way you want to be in life.”

In Personal Shopper, Stewart is so convincing that it’s easy to believe she is in fact a “nobody,” shadowing a “somebody.”

Might she actually desire anonymity? Possibly. “The biggest issue I have is meeting people for the first time and having to deal with the fact that they already have a specific impression of who I am. Those impressions are not necessarily wrong, but they’re very subjective. People think they know you from what they’ve read or from some of the characters they’ve seen you play in your films, and you’re put in the position of having to correct or adjust those impressions.”

If she could be anonymous again she says she’d like to “go to a mall or someplace where I would be able to observe a lot of people. Being curious about people and wanting to observe and study people is one of the reasons I became interested in acting. I would love to be able to meet someone, look them straight in the face, and not be recognized. It would be really interesting to be able to meet someone that way and not have any preconceived impressions get in the way of that process.”

It’s the processes of art and of life that Stewart is committed to now, not an image of herself that can be endlessly consumed. “I try to do the things that I feel passionate about and focus on the work rather than on the money involved. . . . My view is that you can’t be truly happy unless you keep reflecting on your life and questioning your actions and decisions and whether you’re doing the right thing or not,” she says.

Has she beaten her anxiety, the conflictedness about fame that kept her guard up for so long? “I’ve learnt that you shouldn’t worry so much about how things might not be how you would like them to be, but instead focus on all the good things that are around. I try to get out and do things that are going to make me feel happy and be creative in my life. I don’t want to be passive when it comes to leading my life.”

Watch the Personal Shopper trailer below: