Health is on all of our mindsduring The COVID-19 pandemic.

More than 800,000 people have died from this dangerous virus around the world.

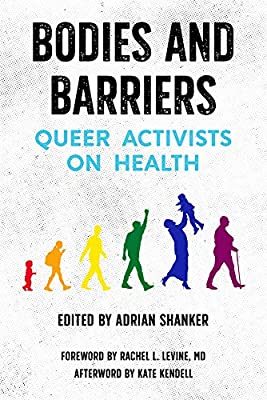

The release of the critically-acclaimed new anthology Bodies and Barriers: Queer Activists on Health (PM Press) is timely.

This book, edited by Pennsylvania-based activist Adrian Shanker, includes essays by 26 queer activists from around the world, including many LGBTQ women who write candidly about the barriers to care they have experienced and how to change the systems of care so that LGBTQ people can attain our highest quality of health.

The following are short excerpts from some of the LGBTQ women included in Bodies and Barriers.

Liz Margolies, New York City, founder of the National LGBT Cancer Network:

I don’t have cancer. So far. That is a good thing.

But over a ten-year period, I accompanied four queer women to the edge of the cancer cliff, and then watched them all tumble over it and die.

These were not just four people I knew and lost; they were four of my favorite people on this planet.

Adria, Ruth, Jo, and Shirley all died of ovarian cancer in their fifties. During that same decade, three other friends were treated for breast cancer.

What are the odds of this? Slim, I would have thought, but it turns out that this massive loss is not the product of bum luck or a poor choice of friends on my part. This is what health disparities look like in real life. When I was forced to understand this by falling face first into my grief and rage, I set out to tell the world. I was in my fifties too.

Please don’t pull out that inaccurate trope that “cancer doesn’t discriminate.

” I’ve heard it way too many times, and I’ve lost my patience with explaining. Yes, rogue cells are rogue cells, but we cannot tease out the lives of the errant cells from the social conditions in which the whole body lives.

Robyn Ochs, Boston, MA, editor of Bi Women Quarterly:

In my twenties, during an annual check-up with a new primary care physician, we had the following conversation:

Physician: “Are you sexually active?”

Me: “Yes.”

Physician: “What kind of birth control do you use?”

At the time, I was in a monogamous relationship with a woman. I

wanted to reply, flippantly, “We use the lesbian method.” But I wasn’t that brave. I hemmed and hawed and squirmed uncomfortably and finally managed to state that my partner is a woman. It was awkward and uncomfortable.

A couple of years later, that relationship had ended, and I was in a new relationship with a man. I suspected there was a note in my chart saying I was a lesbian, and I finally, awkwardly, told my doctor, “I’m bisexual,” and got fitted for a diaphragm.

Liz Bradbury, Allentown, PA, director of the Training Institute at Bradbury-Sullivan LGBT Community Center:

During a recent panel I facilitated for doctors, nurses, and other professionals at a major hospital network, an older transgender adult patient recounted the stress she felt when hospital staff refused to use her chosen name and appropriate pronouns and refused to acknowledge her gender. This happened even though she had clearly explained her gender identity, name, and pronouns to her physician and the staff on several occasions, and her gender identity information was in her chart.

When she expressed her concern in a phone call, she explained that as a patient she felt that the constant and unapologetic disregard for her gender identity verged on discrimination. She suggested the staff receive some kind of training. A few minutes later, she received an angry return call from the physician himself, insisting that she explain exactly what this discrimination had been. Before the patient could even finish a sentence, the physician cut her off.

He sternly told her at length that she was wrong, and that she could no longer be his patient.

Kate Kendell, San Francisco, CA, former executive director of National Center for Lesbian Rights:

Throughout my career, I’ve been involved with some of the LGBT movement’s greatest fights: marriage equality, nondiscrimination in the workplace, parenting rights, inclusion in sports, ending conversion therapy, protecting youth, elders, and LGBT families.

The common thread that links all these issues is health and well-being. It is not possible to be a healthy, vital person if you are under assault for who you are.

We’ve come a long way from the time when LGBT people were dying left and right from a treatable virus to witnessing some of those early AIDS activists marrying longtime partners.

But the LGBT community still experiences open hostility and disregard from health care professionals, some LGBT health needs are still not covered equitably by health insurers, and policy makers still sometimes lack the political will to advocate for equitable policies for our community.

From obstetricians refusing to treat lesbians, to gay men being ridiculed for wanting a prescription for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Health care professionals can do better. Policy makers can do better. All of us can do better.

Our movement for equality, for liberation, has been breathtaking in its gains. But we still fight for our humanity, our health, and our happi- ness. The priority for a new generation must be the health of every one of us and the promise of a long, healthy, fully embraced life.

Support LGBTQ Media