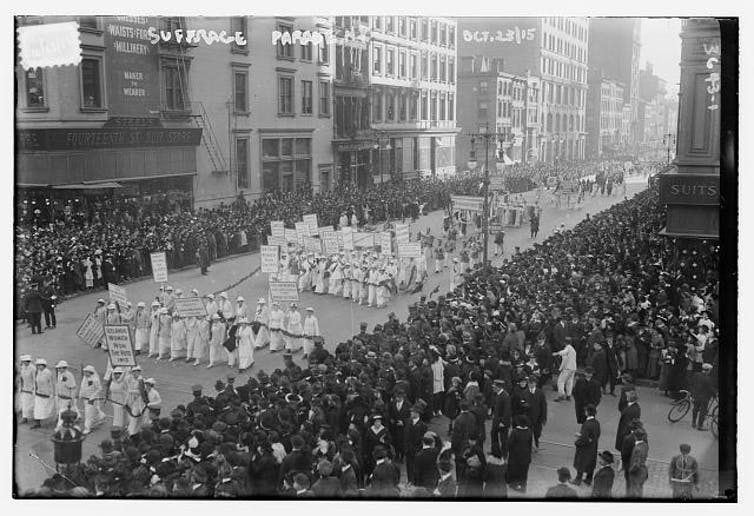

As Americans commemorate the centennial of the 19th Amendment, which granted voting rights to some but not all women, it is important to acknowledge the lesbian leaders of the suffrage movement.

A leadership team of three women with “lesbian-like” relationships – Jane Addams, Sophonisba Breckinridge and Anna Howard Shaw – took control of the suffrage movement in 1911.

My research suggests that the personal lives of these suffrage leaders shaped their political agendas. Rather than emphasizing differences of gender, race, ethnicity and class, they advanced equal rights for all Americans.

Emphasizing differences

Suffrage scholarship has long acknowledged a shift “from justice to expediency” – from an emphasis on natural rights to an emphasis on gender distinctions – in the movement at the turn of the century.

The 1848 Declaration of Sentiments, a founding document of the suffrage struggle, proudly insisted that “all men and women are created equal.”

However, by the early 20th century, many of the movement’s new adherents emphasized women’s differences from men. To gain support, they argued that female voters would engage in “social housekeeping” and “clean up” corrupt politics.

Some suffragists, including women’s rights pioneer Elizabeth Cady Stanton, also increasingly emphasized racial, class and ethnic differences. After the Civil War, when the 15th Amendment enfranchised black men but ignored all women, white suffrage leaders excluded African American women from the movement.

By the 1890s, some had begun to advocate “educated suffrage,” code for literacy requirements that would extend voting rights to educated, white, middle-class women, but prevent many African Americans, immigrants and working-class citizens from casting ballots.

A new leadership team

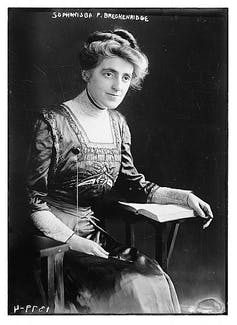

At the 1911 meeting of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the membership elected Jane Addams as first vice president and Sophonisba Breckinridge as second vice president.

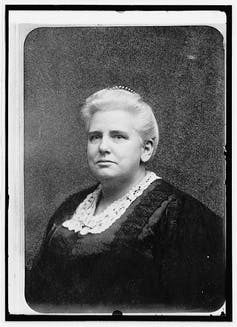

The new officers joined a leadership team headed by Anna Howard Shaw, an ordained minister who served as NAWSA’s president from 1904 to 1915.

For the next year, women who loved other women held the top three positions in the nation’s largest feminist organization.

None of these women publicly claimed a lesbian identity. Nonetheless, like other leaders in women’s rights, higher education and social reform, all three women had significant same-sex relationships.

Shaw relied on her companion and secretary, Lucy E. Anthony – suffrage pioneer Susan B. Anthony’s niece – to assist her in guiding the woman suffrage movement.

Addams, head of the Chicago settlement house Hull House, enjoyed a long and loving relationship with philanthropist Mary Rozet Smith, who supported her both emotionally and financially. As Addams’ nephew explained, Smith dedicated herself to “making life easier for Jane Addams. That was her career.”

And, as my recent biography of Breckinridge demonstrates, her intimate relationship with Edith Abbott, dean of the University of Chicago’s School of Social Service Administration, helped her pioneer the social work profession and promote social welfare policy.

Promoting conventional femininity

Opponents of woman suffrage used images of suffragists as unattractive man-haters to discredit the movement.

To counter such stereotypes, suffrage leaders promoted a public image of conventional femininity. Shaw, who previously sported short hair, grew her hair long and wore it in a conservative chignon.

“I learned that no woman in public life can afford to make herself conspicuous by any eccentricity of dress or appearance,” she noted, because negative attention “injures the cause she represents.”

Suffrage leaders also emphasized women’s roles as wives and mothers. Addams and Breckinridge were founding members of the Woman’s City Club of Chicago, which produced a popular pro-suffrage graphic that illustrated the connections between domestic life and local government. NAWSA adopted the image as its own, featuring it on suffrage posters.

To avoid criticism and gain support, NAWSA’s leaders upheld conventional femininity. But this was not the whole story.

Demanding equality for all

In a 1910 speech, Breckinridge predicted that the time was coming “when man and woman would stand on the same industrial plane and their wages would be equalized by an equal social condition.”

Breckinridge’s lesbian-like lifestyle helps explain her stance on gender equality. As a single, self-supporting woman, she understood that many women, like herself, could not rely on men for financial security.

Thus, at the same time that she promoted equal voting rights, she also championed financial support for single mothers and maximum hour and minimum wage legislation for women workers.

As members of the Immigrants’ Protective League and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, both Breckinridge and Addams rejected exclusionary strategies.

Addams protested proposed literacy tests for immigrants. Breckinridge coauthored a report advocating education, rather than employment, for working class youth.

The new lesbian leadership team also welcomed African American participation in the movement.

W. E. B. Du Bois, editor of the NAACP publication The Crisis, had publicly criticized NAWSA’s racism, warning that the movement’s mission was becoming “Votes for White Women Only.” He also published numerous editorials and articles in support of woman suffrage.

Breckinridge advocated inviting Du Bois to speak at the suffrage organization’s 1912 meeting. His participation signaled NAWSA’s growing commitment to racial equality.

In 1911, NAWSA had refused to allow a resolution linking woman suffrage with African American rights to be presented at its annual meeting. In 1912, however, NAWSA published Du Bois’s speech, “Disfranchisement,” which did just that, advocating a “Democracy of Sex and Color.”

This lesbian leadership team lasted for only a year. But while it operated, these leaders made the suffrage movement more diverse and inclusive.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

Anya Jabour, Regents Professor of History, The University of Montana

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.