Cicely-Belle Blain looks beyond aesthetics to find out what we really mean by “femme”

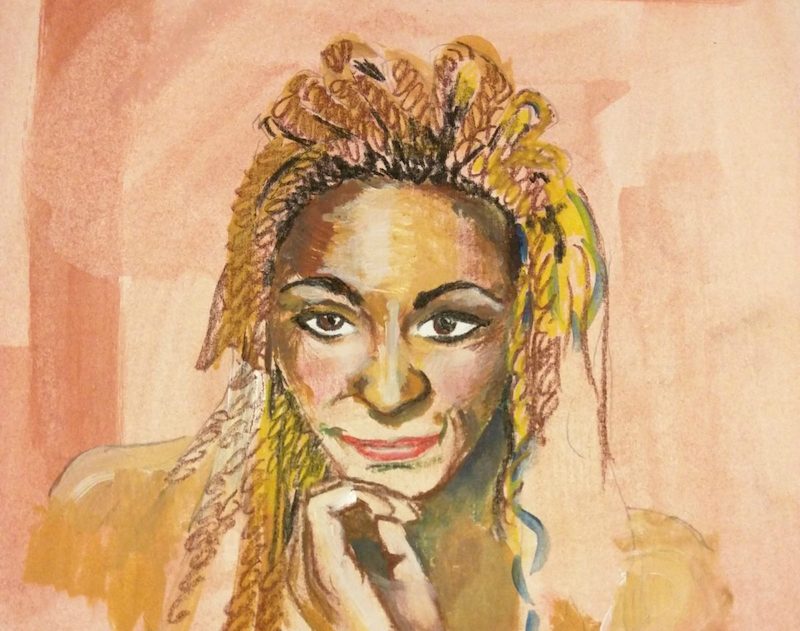

Illustration by Antoinette Blain

Femme. It’s a word I first heard when I read Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg – a coming-of-age novel about a young person who struggles with their sexual and gender identity in oppressive 1950s America. The book details the underground life of queer communities in urban environments and, most profoundly, the dichotomy and roles of butches and femmes. Butches were strong, dominant, rough, stoic. Femmes were soft, promiscuous, vulnerable and submissive. Of course, relationships could not exist without being folded into heteronormative scripts and so by that logic, butches were men and femmes were women. That’s it. A binary, opposing forces, a clear and linear division between the two different types of lesbian women.

Fast forward to 2012 and I’m coming out to my parents on the telephone. My dad is shouting in the background, “I knew she was a lezza!” and my mum is trying to act nonchalant and be a cool and supportive parent. I’m halfway to blossoming into the fierce floral femme I am now and so it is my dad’s automatic assumption that my partner will be “the man”. He has no problem with a queer child but is still looking to fulfil a myriad of predetermined scripts that make him feel comfortable. He knows she won’t be a man – not one that meets his cisnormative standards – but he still wants to see a binary. The man to the woman, so the butch to the femme.

Read the rest of this article in the March issue of DIVA, available to buy in print or digitally here.

Only reading DIVA online? You're missing out. For more news, reviews and commentary, check out the latest issue. It's pretty badass, if we do say so ourselves.

divadigital.co.uk // divadirect.co.uk