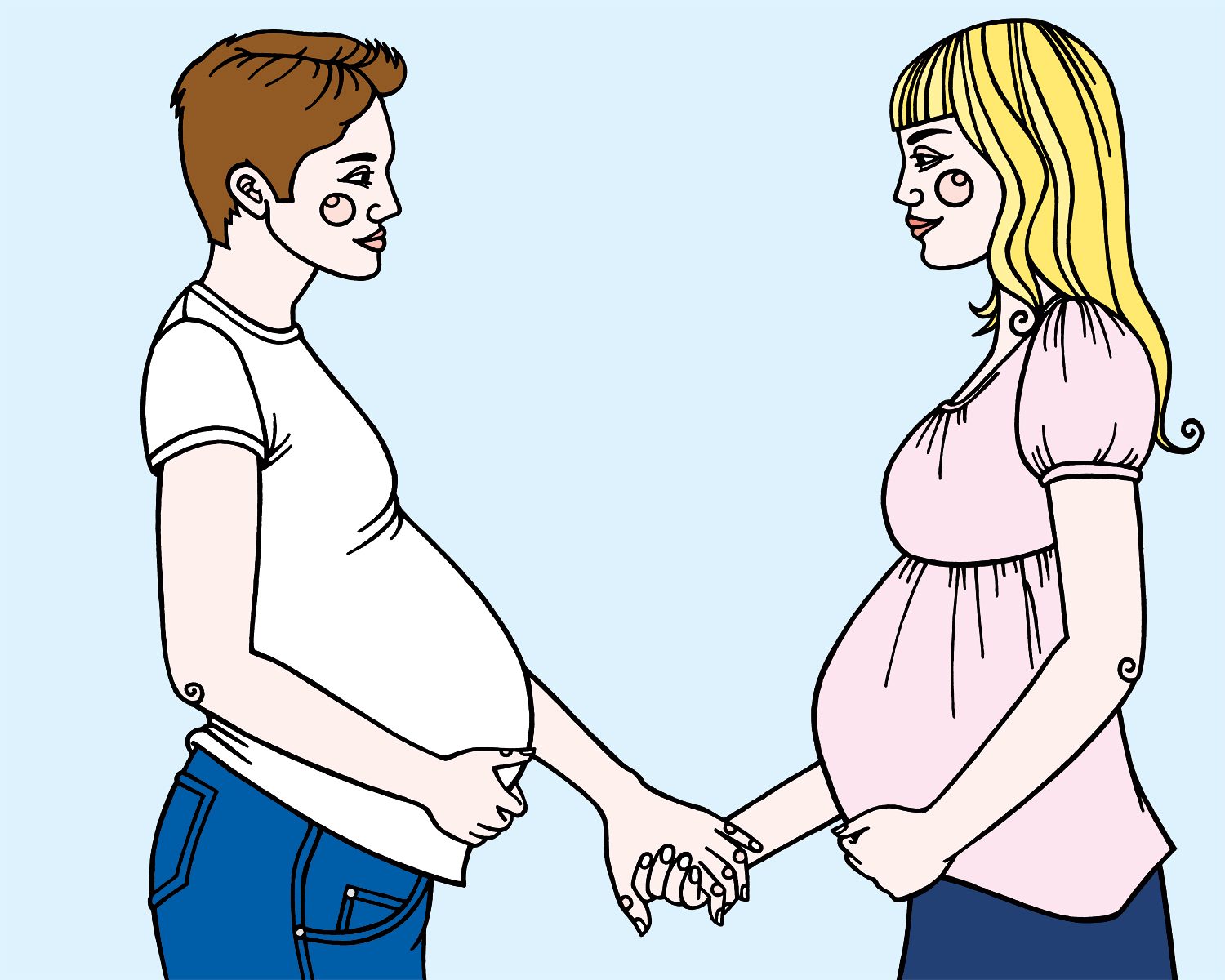

A lesbian couple gets pregnant””at the same time.

My sons are 7 months and 3 months old. The number one question strangers ask when I explain that my partner gave birth to one and I gave birth to the other four months apart is: “Did you mean to do that?” I’d always assumed that it was common knowledge that lesbians couldn’t knock each other up by accident. If they could, I wouldn’t have reached the advanced age of 37 years old before acquiring not one but two newborns.

On the other hand, to say that we planned it this way might be overstating the case. “It was a bit whimsical,” I usually murmur.

“Did you use the same sperm?” one woman in a Trader Joe’s parking lot asked.

“We used the same donor,” I said.

The typical response here is the annoying exclamation, “Then they are brothers!” I have yet to find a charming way to reply that they are brothers because they have the same mothers, not because they—along with 10 other families’ kids—have the same donor.

“You are pioneers,” our mindfulness birthing coach told us before our second son was born. “And pioneers never have it easy.”

So what were we doing? Were we crazy? Driven by the relentless beating of two biological clocks to throw caution to the winds, carpe diem, and let the chips fall where they may (to mix metaphors the way banks spin sperm)? In a word, yes.

We’d each always wanted to have a baby, in the sweetly innocent, romantic way that people who don’t have babies can want them. And when, after 12 years of friendship, we plunged into family building together, we were both at or about that treacherous age of 35, which is when the medical establishment likes to pretend that fertility drops off a cliff, eggs running, lemming-like, after it. We heard horror stories, and I tried to get pregnant a few times without success.

Then Angie tried once, and lo! she was pregnant. (She says it’s lucky she’s a lesbian, or she’d probably have gotten knocked up in high school and be living in a trailer somewhere with a passel of kids; I say that I’m just that good at knocking her up.)

We didn’t know how this should impact my own efforts to get pregnant. It didn’t seem as though I should just blithely keep trying, and so I skipped a cycle. It freaked me out. What if I waited and then I never got pregnant? We spent an unfortunate amount of time worrying about this issue. I was tormented by the situation, and, in turn, I tormented Angie.

And then she had a miscarriage. Having a miscarriage is a little like being a lesbian. But less fun. You think it’s not a big deal and not very common before if happens to you; afterward, you learn that it has huge emotional consequences and that a heck of a lot of people share the experience. Miscarriage is a cultural secret.

It shook up our sense of being at the helm of this project. We stopped debating how things should turn out because we realized that we had very little say in the matter. We agreed that we would each continue to try to get pregnant, no matter what, because being pregnant didn’t turn out to guarantee us a baby.

Then—well, months and months later—I got pregnant. This time, we were tentative about the situation, but still…if Angie kept trying, there was always the chance, however slight, that we’d end up with two tiny babies very close in age. Whenever we talked to anyone about both of us trying to get pregnant—our lawyer, our doctor, my mother—everyone told us the same story: “Did you hear about the lesbian couple that both got pregnant at the exact same time…with twins? They went from zero to four all at once!”

When you don’t have kids, you just kind of know that it’s hard. Hard work, hard hours, but mostly, it’s hard to imagine just what it entails.

Angie tried once more and didn’t turn up with child. She skipped a month or two—going against our rule that we should keep trying, no matter what. We had a decision to make.

Oddly enough, after all the lists and sharing, the matter boiled down to Angie’s strong desire for a Leo (her own astrological sign). She would have had a Leo if she hadn’t miscarried, and if she got pregnant this upcoming cycle, she’d be due for a Leo again. I don’t really believe in astrology—though I like any system for talking about people and their behavior. But I do believe in listening, and giving serious weight, to whatever moves Angie.

We struck a deal: She’d try this one last time, and if she didn’t get pregnant, we’d wait until our first baby was born to try again.

Which is how we came to be pregnant at the same time.

The main difference in our experiences was that nobody knew that Angie was pregnant. This is not because she didn’t get big and all that. It was more about the clothes she wore—her own oversized men’s clothes—versus the hand-me-down maternity blouses and dresses I’d acquired and tried to wear with a little contradictory, body-revealing flair. (In my opinion, femme is about just these kinds of contradictions: fulfilling some norm while trending against it at the same time.)

Then there was Angie’s denial: It was easier for her to believe that I would make her a parent than that she would do it herself, too. In late summer, just before she was due, a woman approached her in a café and asked if she was expecting a baby. “There’s my baby,” Angie replied, pointing to our first son.

Maybe most folks assumed that she was just drinking a heck of a lot of beer.

Actually there are advantages to being pregnant at the same time as your partner. No one has any brain power anymore, so conversations—requiring words, as they do—are necessarily limited. Still, there’s a telepathic bond that comes from sharing the pauses in each other’s sentences.

On the other hand, who should do the heavy lifting? Who should hand out the bonbons and who should sit on the couch nibbling and waiting for a foot massage? Like all good lesbians, we took turns.

And like any butch and femme couple, we understood that we each had our own way of being in the world, which surely included being pregnant. I went to prenatal yoga classes, practiced hypnobirthing and had the baby at home. Angie asked the doctor about weightlifting during gestation, took private birthing classes and elected to go to the hospital when the time came.

The lesbian baby boom announced to the world that being gay didn’t mean we couldn’t become parents. But why stop there? In a two-uterus relationship, much more is possible. I know of other couples who are both trying to get pregnant at the same time. And word on the street has it that the lesbian couple with the double sets of twins is making it work.

Now we are in the throes of raising our two infants (the first a Taurus—named Leo—and the second, two weeks overdue, a Virgo), and we know that we had no idea what we were getting ourselves into—the good, the hard and the seriously messy. If Irish twins are those siblings born 11 or 13 months apart, ours are lesbian twins, or, as a friend called them, San Francisco twins.

But when you think of it that way, as having twins, all the advantages to our approach come to light. After all, the increasingly dated method of one person doing all the childbearing is based on a strictly heterosexual model. Ask any woman who had twins the old-fashioned way—one beleaguered pregnant body, one nursing mom. We’re just sharing the work 50-50. The old-school feminists who preceded our generation would be proud.