This November 18th marks the 40th anniversary of the Jonestown massacre.

The mass murder-suicide was the largest casualty of American citizens before 9/11.

With forty years since the Jonestown massacre, a more disturbing image of the Revered Jim Jones’s treatment toward his LGBTQ parishioners emerges.

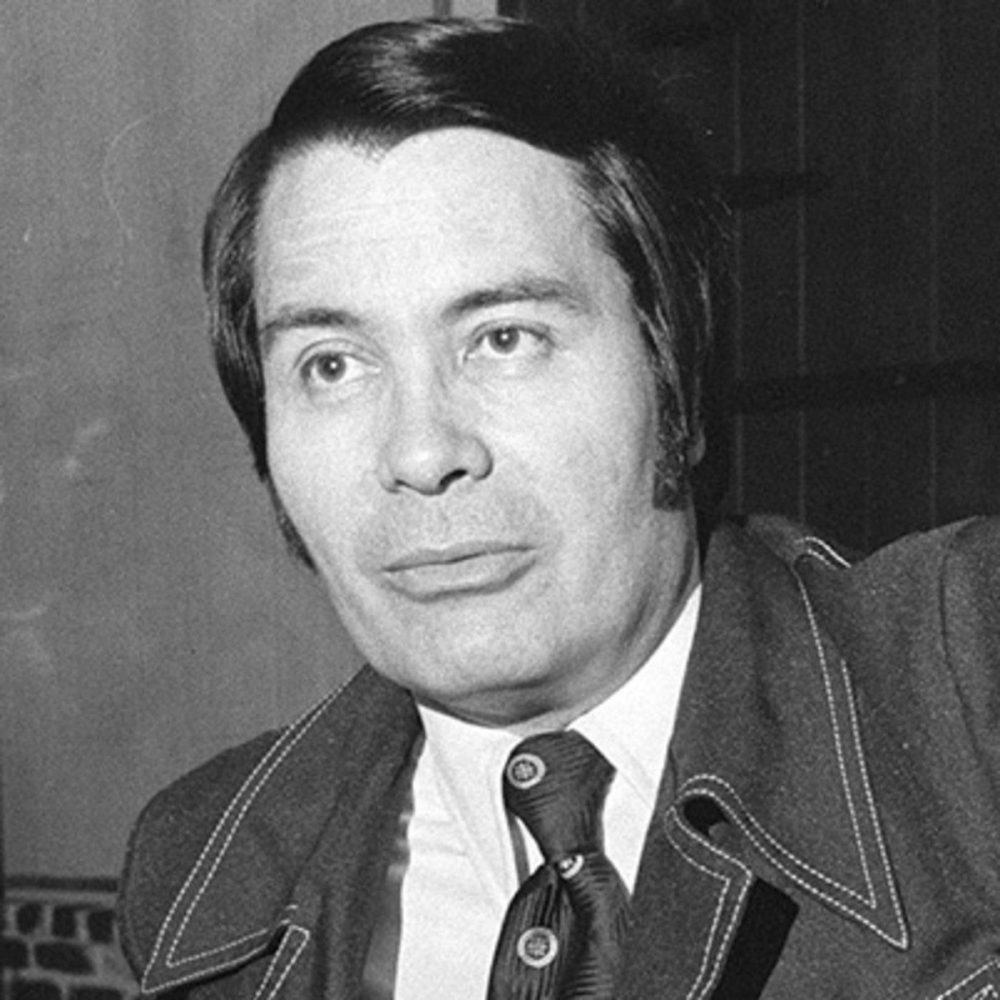

Jones was the charismatic white founder and cult leader of the Peoples Temple, a San Francisco-based evangelical church. And, he was the founder of the “Peoples Temple Agricultural Project,” a utopian socialist commune in a remote jungle outpost in Guyana, South America. Also, Jones was a megalomaniacal bisexual and sexual molester.

As a sympathizer with the oppressed and social outcasts, it is not surprising Jones developed a large and loyal following of African Americans. He also developed a large following of LGBTQs.

Over 900 members of the People’s Temple died in the Jonestown massacre in 1978. Of the 900 plus, approximately, 75 percent of Peoples Temple congregants were African American, 20 percent were white, and 5 percent were Asian, LatinX, and Native American. The majority of its black congregants were women, while its core leadership was predominantly white as too is the historical records and visual optics of the event. And, as in the Black Church, black women were “the backbone” of Peoples Temple. Sadly, the majority of Jonestown ’s victims were African American women, too.

Jones and the Peoples Temple were a ubiquitous presence in the Bay area. As an influential church body in city politics, the Peoples Temple had a public pro-LGBTQ and civil rights image in San Francisco in the 1970s.

As an “open and affirming” church that welcomed LGBTQs in the era of the Florida sunshine homophobe poster-girl Anita Bryant and her “Save the Children” campaign, the Peoples Temple was a safe and sacred sanctuary. The Peoples Temple marched in Gay Pride and embraced a social gospel of radical inclusion. Jones had a sizeable LGBTQ following that kept growing as did his African American audience. The LGBTQ community followed Jones and expanded in numbers at each church he had from Indiana, Ukiah, San Francisco to Guyana. LGBTQ parishioners were involved in every aspect of church life, governance, and activities. So accepting was the People’s Temple that the lead soloist had an open relationship with the church organist. In Guyana, the community was actively involved in building Jones’s utopian town. Sadly, many of his LGBTQ parishioners died along with him.

The number of LGBTQ deaths in the Jonestown massacre is not presently known. Their stories about Jim Jones as ex-Temple parishioners and Jonestown survivors, however, are now emerging.

Many would argue that Jones public pro-gay persona was both strategically political and personally self-serving.

Jones and his church were pivotal in the 1975 mayoral election of George Moscone who subsequently appointed Jones as chairman of the San Francisco Housing Authority Commission. Before Jones was chair of the housing commission Jones’s activism intersected with Harvey Milk’s, the first openly gay to be elected to the city’s first district elections for Board of Supervisors in November 1977. Milk was a frequent speaker at rallies at the Peoples Temple and wrote to Jones frequently afterward expressing his thoughts. Exhilarated from one of the rallies he spoke at the Peoples Temple Milk wrote Jones the following:

“Rev Jim, It may take me many a day to come back down from the high that I reach today. I found something dear today. I found a sense of being that makes up for all the hours and energy placed in a fight. I found what you wanted me to find. I shall be back. For I can never leave.”

Oddly, Jones’s and Milk’s death were nine days apart in November 1978. Paul VanDeCarr wrote a somber piece about their deaths in “The Advocate” titled “Death of Dreams,” stating San Franciscans spirits nearly broke when two revered icons who preached radical equality in an era of little hope and activism were now gone.

While Jones was quickly becoming America’s beloved civil rights warrior for the downtrodden, he also had a Dr. Jerkyll and Mr. Hyde persona that skillfully fooled and manipulated the people who trusted him the most.

I ask myself “was Rev. Jim Jones, a closeted gay? Were the many heterosexual dalliances with women and the family man image with dozens of children around him merely his gay coverup?”

“Jones had occasional sex with male followers” but “never as often as he did with women, “ according to Jeff Guinn’s book “The Road to Jonestown.” However, it’s ex-Temple followers and Jonestown survivors who can give first-hand accounts.

“Jim said that all of us were homosexuals,” Joyce Houston, an ex-Temple follower, said in the “Jonestown” documentary. “Everyone except [him]. He was the only heterosexual on the planet, and that the women were all lesbians; the guys were all gay. And so anyone who showed an interest in sex was just compensating.”

His sexual ambiguity and animus toward homoeroticism were impulses he could neither closet nor control. Instead, he used sexual assault on men as one of his weapons. For example, Jones openly and in public sexually molested a male congregant in front of followers to “prove the man’s own homosexual tendencies.” Other times when Jones engaged in gay sex, he purportedly was doing it as a symbolic act to have men connect with him.

Jim Jones was a man of many contradictions, especially if trying to assess his relationship with the LGBTQ community. Michael Bellefountaine’s book, “A Lavender Look At The Temple,” attempts to tackle the issue.

Very little is publicly disclosed about ex-Temple LGBTQ parishioners and Jonestown survivors. It’s time their stories come out.