Too many of us keep the n-word alive.

What was expected to be a friendly and light-hearted skewering of political and media elites at the White House correspondents’ dinner by Larry Wilmore, comedian and host of Comedy Central’s The Nightly Show, turned into a night of off-color remarks, edgy jabs where you heard moans and groans.

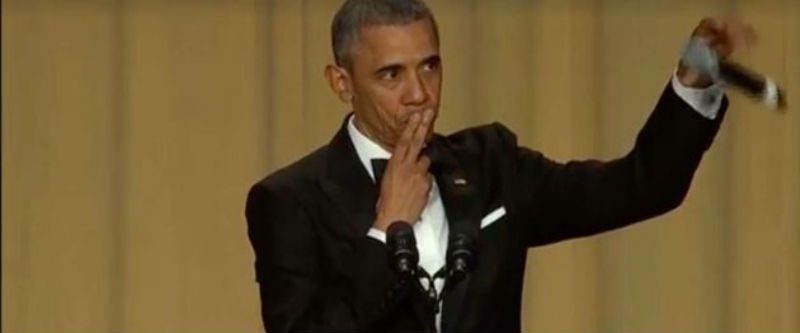

In his closing remarks thanking Obama for his tenure as president and the mark he has made in the world, Wilmore dropped the n-word. And at that moment you heard audible gasps and saw visible grimaces of shock, pain and embarrassment.

“When I was a kid, I lived in a country where people couldn’t accept a black quarterback,” Wilmore said. "Now think about that. A black man was thought by his mere color not good enough to lead a football team — and now, to live in your time, Mr. President, when a black man can lead the entire free world. Words alone do me no justice. So, Mr. President, if i’m going to keep it 100: Yo, Barry, you did it, my n—-. You did it.”

When Wilmore dropped the n-word Twitter blew up. And what will probably be debated for a while is whether Wilmore went too far. Many of the comments on twitter were asking is the n-word what the American public need to hear associated to Obama’s last months in office, especially given the racial rollercoaster the entire country has been on since Obama took office and evident by the treatment of him.

Wilmore won’t be the last African American comedian to use the epithet in public discourse. But how it’s used means everything.

For example, last year when news broke that President Obama used the n-word during the podcast interview “WFT with Marc Maron” about America’s racial history, it caused shock waves. We are shocked because we are all confused as to when — if ever — there is an appropriate context to use the word.

On CNN, legal analyst Sunny Hostin said that Obama’s use of the word was inappropriate because of his office, and given the history of the word itself. New York Times columnist Charles Blow countered Hostin’s assertion, pointing out that Obama used the word correctly: as a teaching moment.

The confusion illustrates what happens when an epithet like the n-word, once hurled at African-Americans in this country and banned from polite conversation, now has a broad-based cultural acceptance in our society.

Many African-Americans, and not just the hip-hop generation, say that reclaiming the n-word serves as an act of group agency and as a form of resistance against the dominate culture’s use of it. In other words, only they have a license to use it.

However, the notion that it is acceptable for African-Americans to use the n-word with each other yet it is considered racist for others outside the race to use it unquestionably sets up a double standard. And because language is a public enterprise, the notion that one ethnic group has property rights to the term is an absurdly narrow argument. The fact that African-Americans have appropriated the n-word does not negate our long history of self-hatred.

Unfortunately, controversies seem to erupt regularly into public view. In July 2008, the Rev. Jesse Jackson used the n-word to refer to Obama. Although Jackson and a cadre of African-American leaders conducted a mock funeral in 2007 for the n-word at the NAACP convention in Detroit, the fact that it slipped so approvingly from his mouth illustrates its lingering power.

In January 2011, the kerfuffle concerning the n-word focused on Samuel Langhorne Clemens, known as Mark Twain, in the NewSouth Books edition of his 1885 classic, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. In the original edition of the book, the epithet is used 219 times. In a combined effort to rekindle interest in this Twain classic and to tamp down the flame and fury the use of the n-word engenders, Alan Gribben — editor of the NewSouth Edition, and an English professor at Auburn University in Alabama — replaced the n-word with the word “slave.”

In short, the n-word is firmly embedded in the lexicon of racist language used to disparage African-Americans. Our culture’s neo-revisionist use of the n-word makes it even harder to purge the sting of the word from the American psyche.

Why?

Because language is a representation of culture. Language re-inscribes and perpetuates ideas and assumptions about race, gender, and sexual orientation that we consciously and unconsciously articulate in our everyday conversations about ourselves and the rest of the world, and consequently transmit generationally.

Obama used the n-word appropriately, as an illustration that racism is very much alive. Wilmore used it as a term of endearment to say he can use the word but no white person can. In truth, no one should.

Too many of us keep the n-word alive. It also allows Americans to become numb to the use and abuse of the power this racial epithet still wields, thwarting the daily struggle that many of us undertake to try to ameliorate race relations.

The last thing Obama’s final roasting didn’t need to end on is associating him with the n-word – even as an act of thanks and brotherly love.