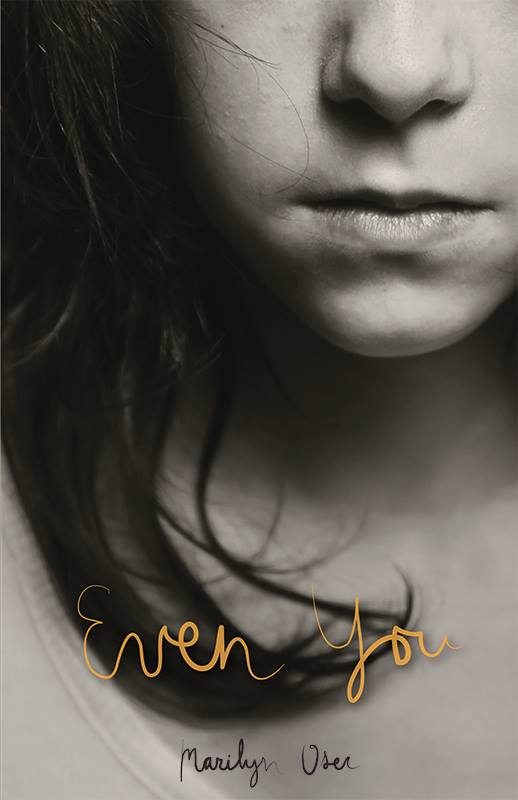

An author promoting her lesbian-themed book faces discrimination, head on.

I’m an author on a book tour trying to get the word out about my new novel—which, by the way, has been reviewed as “riveting from beginning to end” and “a profound work of literature.” But never mind that.

I’ve been told that another writer—let’s call her G—with whom I’ve been scheduled for two book talk “conversations,” has, after last night’s event, elected to revert to the standard format of separate readings. Instead of talking together, first one author will read and do Q & A, followed by the second. In addition, G asks to go first, because some of her friends will be leaving after her reading.

It’s fine. I’m comfortable with either format, and though I tried mightily to draw G out in conversation last night in DC, I’m just as happy (you might say relieved) to change to separate readings for our event in Manhattan.

It’s her reason for the change I don’t like.

“As a priest,” her publicist has written to tell me, “She has many friends who are not open to gay issues.” So here’s a new twist on an old theme: some of my best friends are gay…bashers.

No wonder G wouldn’t engage with me onstage. As an introduction to me and my work, I said, “Even You is written by two women about two women, exploring their coming together and splitting apart as lovers.”

G introduced herself to our audience as one who has spent her later life ministering to the poorest and most downtrodden among us—those neediest whom no one else would touch.

Hypocrisy doesn’t go down easy with me.

Nor am I used to turning the other cheek when slapped in the face. I have no doubt that the publicist was doing her best to be politic. I’m glad I couldn’t be a fly on the wall—or rather, in the phone lines— when that discussion with G went down. Some things I’d rather not hear.

I plan during our second appearance to be as cordial and accommodating as I was at the last. All the same, I’ve been insulted, and it hurts. Most people I meet don’t seem to give two figs about who I’ve lived my life with or who I’ve chosen to love. It seems I’ve been in a charmed New York bubble most of my life.

During our presentation at a well-known New York feminist bookstore, I could get up at the podium and announce, “I’m about to use the term LESBIAN. So let’s wait a moment to allow all the homophobes among G’s friends and admirers to leave.” I’m sorely tempted.

Is it possible for G to be an activist for the so-called downtrodden and yet slap a person who has been a part of that said group for decades? Can you be a feminist and fight for women’s rights but not fight for the rights of women who love women?

As I promote my book, with its strong lesbian story, I am reminded that bias and homophobia are still an active part of our culture, even to those who think that they are cultured. So to G and her friends I say this: as an activist all my life, as one who has been among the downtrodden, and as one who is a feminist—we don’t need you. Feminism stands for all women, and if you and your friends have an issue with my loving a woman, then you, Miss G, were never a feminist, nor ever a true voice for the downtrodden.