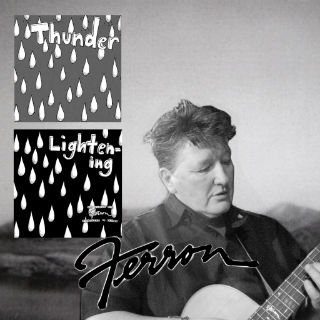

The Canadian folk singer dishes on not being defined by lesbianism and playing house with Bitch.

Since she hit the women’s music scene in 1980, Ferron has been sharing her soulful, poetic songs with our community. Recently, she and Bitch collaborated on “Boulder,” a rich and textured album that helped introduce Ferron to a younger audience and helped to remind the rest of us why we’ve loved her for so long. Ferron speaks to us from her home in Three Rivers, Michigan.

Now that you’ve achieved artistic success, what are your other large goals?

I’m not seeking anything but a life now…I’m not looking to achieve greater fame or to be on the road. I want to incorporate something more sacred or holy in my life.

Does your retreat, the Fen factor into your desire for the sacred and holy?

I did a year’s worth of workshops there…I’m thinking of making it kind of a micro-cabin community, where the Fen would be the longhouse, essentially, and there would be livable cabins on the property and then you just use the big kitchen and the bathroom and everything and you have your own private space, either for people to live long-term, people who can’t afford whole houses, and want community, or else people who want to come and write for a month or more and keep the house empty.

Are you there now?

I’m in Michigan…I did a year’s worth of workshops there and that went pretty good and then the interest kid of died down, I’m not sure the economy or whatever it was. At that point Bitch needed a place to stay for a while, so we rented it to her and she’s been living there since last August.

You’re from Canada, but you’ve really made a home for yourself in the States. Do you consider yourself an American now?

Well no, I’m Canadian. I’m Canadian and I live in the United States because that’s where my work is. I have a green card and that’s how it goes. But I identify Canadian.…I’ve been invited to become an American but deep down I can’t.

I can’t become an American because I wasn’t brought up on the concept of number one. I mean Canadians would think of why just one? Let’s get a group. It’s a different mind-set and a different psychology.

So you identify as Canadian first. In terms of your artistic labels, do you define yourself as a lesbian musician?

I remember the day that we decided [how to define ourselves]. My manager and I, we knew that if I did the lesbian thing it would be a big stigma thing, and it’s kind of like we looked at each other and what she said is, “Well y’know, if you can’t tell the truth when you have nothing to lose, what’s going to happen when you have everything to lose?”

So we started there. And part of it was—my dream was a place where men and women, straight and gay, to be together. And I actually accomplished that with my band, who were three lesbian women and three straight men. And we just love each other.

You launched your musical career during the women’s movement of the 60’s. How did that movement influence your artistic development?

I don’t think I would have happened without the timeliness of the women’s movement. It’s where I come from. I joined it, I met it. I flourished in it. I don’t know that I would have flourished without it. I still would have been a lesbian, which is not so much a sexual identification; it’s a personal identification, but what it is, it’s a sensibility about politics, or life. It has to do with love, actually, instead of power.

I’m talking about the thinking part of it that wants to make the world a better place, I mean ultimately a better place for ourselves, but it ends up making it better for everybody. This is how the world changes, by where our thoughts go.