What is the point of this message?

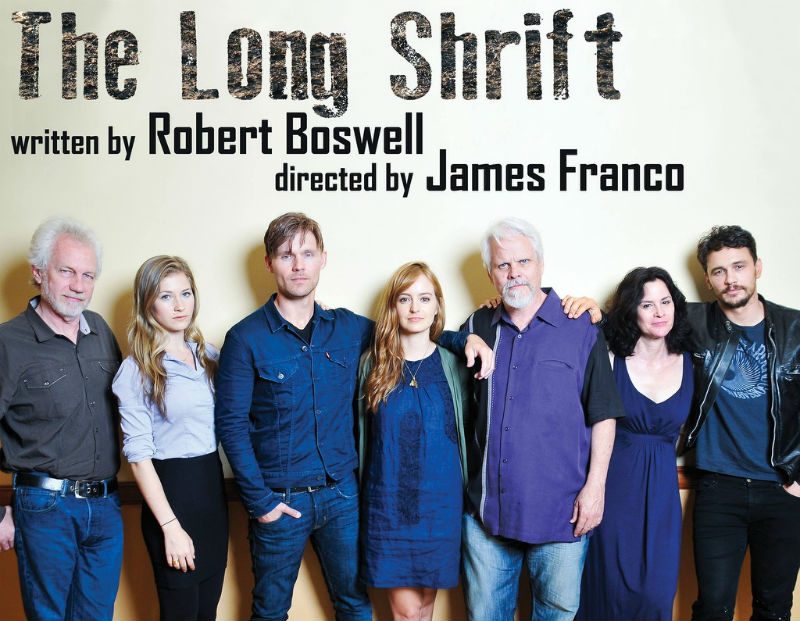

The Long Shrift, directed by James Franco and written by Robert Boswell, examines the fallout from an alleged sexual assault from the accused’s point of view. It was a brave effort. Sexual assault is traditionally seen as a women’s issue, according to anti-sexist author Jackson Katz. The result is normalizing sexual violence by men. Rarely do we see sexual assault dealt with as a men’s issue and it is commendable that the creators of The Long Shrift broke that new ground. Somehow along the way, however, it missed the mark.

Early in the play we meet Sarah and Henry, the accused’s parents played by Ally Sheedy and Brian Lilly. The legal fees from their son’s trial have crushed their finances and they consequentially lost their house. Their marriage is strained, mostly because Sarah doesn’t believe her son’s story and refuses to visit him in prison. The play jumps further along: Richard, their son played by Scott Haze, has been out of prison for several years and his mother has died. Richard was released early because the other party, whose family barely saw a dent in their copious coffers from the trial, recanted her testimony. It was a bittersweet ending to his term with the criminal justice system. The charge was removed from the record, but Richard feels marred for life.

Richard came back to his father’s home to consider attending his high school reunion. Before he can make his decision the other half of the equation, Beth, played by Ahna O’Reilly, confronts him. She wants to talk and understandably Richard does not want to interact with her. What comes during the next 45 minutes was disturbing. We watch Richard play out the masculine stereotypes that fit an accused rapist. He was once a quiet, naive teenager, but he is now a manipulative, aggressive, and unsympathetic psychopath incapable of feeling any emotion. It was the same script throughout: the aggressive male carrying out societal norms and the victim too terrified to use her voice. He repeatedly screams and threatens Beth when she tries to speak to him. In a twisted Oedipal scheme he demands that she wear one of his mother’s dresses to accompany him to the high school reunion. She relents and Richard then uses the school stage to load on more embarrassment. We watch him embrace the rapist mask to repeatedly denigrate and humiliate Beth, and also the comedic relief, Macy played by Allie Gallerani, who we are to take to be a younger version of Beth. If he didn’t rape Beth in high school, then he sure as hell was intent on hurting her now. All that Beth was permitted in rebuttal was a brief outburst and a desperate slap.

During their final confrontation the truth of the situation was revealed. Beth’s truth: she said no, but was too terrified to say no again or fight him lest her physically abusive boyfriend find them at the party. She recanted her testimony because she thought it unfair that her boyfriend’s physical abuse was pinned on Richard. Richard’s truth: He knew that he should have stopped his sexual advances. He did what he thought he should do when left alone in an intimate situation with the popular girl — fuck her while he had the chance, consent be damned.

Both Beth and Richard are broken from the events that occurred after the incident. Richard feels trapped in a script and Beth is an anxious, divorced mess who lost her network. They end the play by agreeing to have dinner on a regular basis, catharsis be damned.

The audience was shorted by a transformation in Richard or a pointed lack thereof. The journey simply wasn’t guided in a way that brought it to a powerful conclusion. Richard barely steps out of his mask so we could see the real person underneath. He is trapped and so is his character, but what is the message they were trying to convey? It wasn’t clear.

Both Richard and Beth were victims of circumstance — lower social economic status meets survivor of sexual and physical violence by two different men — and they and the audience were barely holding on by the end.