Alone and together, a married couple navigates the uncertain terrain of an unprecedented moment.

“She asked me, ‘When do you think we’ll be able to hug again?'” James said. “I said, ‘Right now.’” Both, of course, were wearing masks.

From their opposite ends of this pandemic — one tending to the sick, the other memorializing the dead — both women recognize that everyday comforts are now fraught with risk.

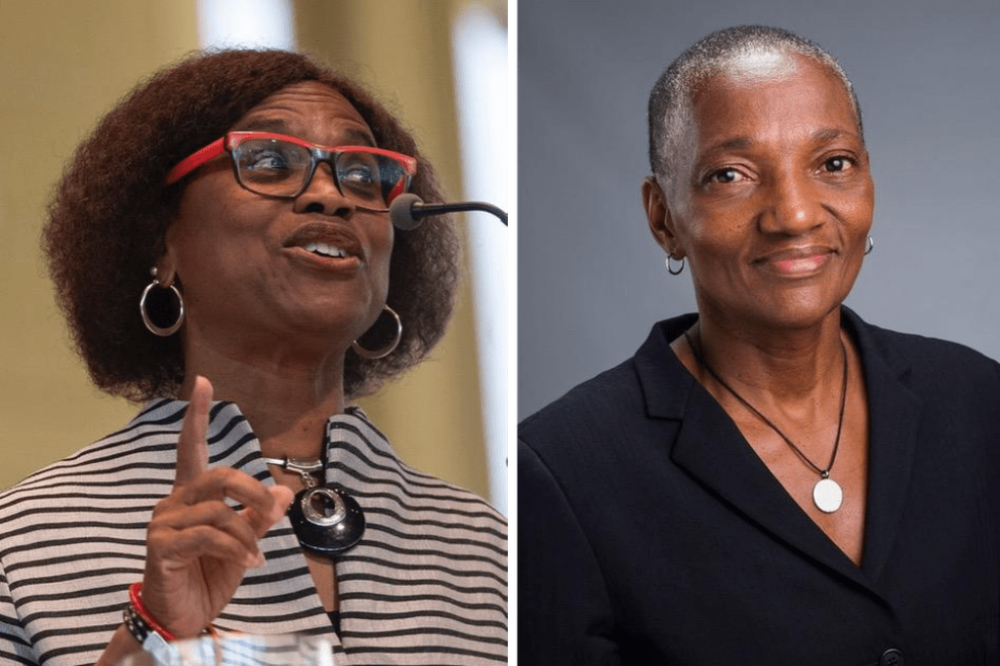

“I work in the ER a couple of days a month. Nothing prepares you to watch people suffer like this,” said James, BMC’s vice president of mission and associate chief medical officer. She is also a member of Mayor Martin J. Walsh’s COVID-19 Health Inequities Task Force.

“I’m primarily in administration, but my office is still on hospital grounds. The ER is a stone’s throw away, so I’m cognizant, when I come home, of what I could be bringing with me — God knows Irene is cognizant of it,” she said. “I wouldn’t want to expose her to that.”

James and Monroe, who is co-host of the WGBH podcast “All Rev’d Up,” stay in touch through FaceTime, texts, and phone calls. They take strolls wearing masks, as well as face shields. (Monroe’s idea.) They stay at least six feet apart, even if it means one of them has to walk in the street. Still, Monroe has maintained a ritual which has marked their 25 years together — she greets James at the door when she comes home.

“When Thea parks in front of the house, I’ll yell out to her, and I’ll open the door. We’ll talk a few minutes before she takes off her shoes and comes up stairs to get into the house,” she said. “We wave to each other, and we stay more than six feet away from each other.” Both wear face masks in the house.

Witnessing up close how COVID-19 ravages the body, James even jogs with her shield and mask, though, she says, “It’s like running with a pillow over your face.

“You cannot be too careful — and I recognize everyone can’t because of where they live, and the limited resources they have. But I keep saying to people, if you can, just be safe,” James said. “That’s the greatest weapon and protection we have against this disease. It’s so weird, so nuanced, and so unpredictable. The best thing you can do is try not to get it, and try not to give it.”

Several times a week, Monroe ushers on their final journey those who’ve perished from COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus. She has performed services in funeral homes with mourners on Zoom. One memorial was held in a park loved by the deceased. Then there was a recent service for a transgender woman. Though her family refused to claim her body, friends insisted on giving her the proper homegoing she deserved.

“The enormity of the grief, pain, and anxiety expressed by mourners, and also the volume of the deaths remind me of the AIDS epidemic when I started out as a young minister,” Monroe said. “People are dying faster than we can funeralize them.”

And, due to social distancing guidelines, it’s not just the mourners who can’t console each other.

“I can’t hold them. I can’t comfort them,” Monroe said. “Part of pastoral care is helping people through this valley of anxiety, fear, and death. And it’s hard to help them through the process when your work is abbreviated by the restrictions this pandemic imposes. It feels incomplete; it does not feel finished.”

Given what this couple experiences on any given day, both recognize that they remain luckier than many. They are employed, they are healthy, and they have each other — albeit with the challenges and frustrations of social distancing.

“We do the air and the virtual hugs. But [Tuesday] was a pivotal moment — we had a real hug. I know that sounds crazy, but it was really important,“ Monroe said. “This is an involuntary separation. But the whole thing is, we want to be able to see each other at the end of this journey.”

During this pandemic, the best we can do is stay clear of those we hold dear until we can hug them again.

article first appeared in The Boston Globe