The queerest folks are Kenny Popora straight family.

When my friend (and fellow gay journalist) Kenny Popora told me last year that he had a memoir coming out I was in disbelief: how could this very young, charming, and seemingly charmed guy have anything complicated, protracted or unresolved in his life to write a memoir about? Turns out, plenty.

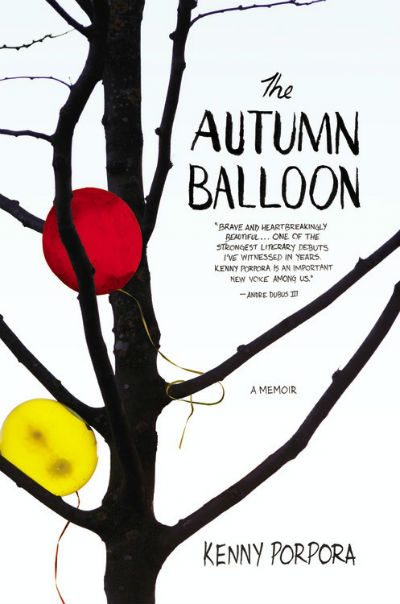

When I read The Autumn Balloon I was blown away—not only because I realized my friend and colleague had been carrying around the weight of a truly torturous past; plus his recollection of it raised dark memories of my own gay brother, and of my baby dyke self struggling in the exurbs that I had tamped down my entire life. I also realized that—especially at Pride—we are all family, and sometimes our gay brothers don’t have an easier ride than we do. The Autumn Balloon (Hachette) is a darkly comic family drama told in brisk, frank prose, set across several states, in which life is excruciatingly dire for young Kenny…and yet, it does get better.

I grabbed a moment to chat with Kenny about what drove him to write the book, and how his things have been on the up and up ever since.

I loved this book, even though it was at times uncomfortable to read. Kirkus called it “a piercing first book.” When did you first realize you had a memoir in you?

When I first started writing about my family and the people I’d lost, it wasn’t with the intention of publishing a memoir, but more a way for me to spend time with them. I missed their voices and their stories, and this was a way for me to spend every day with them, reliving those memories. It wasn’t until I had a few chapters written that I realized it could be something beyond that, a fully developed story.

The book traces the beginnings of your identity as a young gay man and as a writer. But it’s more about you becoming a writer. Why was it important to tell this story of the awful place you came from?

I’d like to think this is a story about the power of the individual. No matter where you come from, eventually you’re going to come up against great odds, and somebody in your life is going to ask if you know what your chances are. This story is about our ability to beat whatever terrible odds we’re dealt, to rewrite our histories, to create our own worlds, and rebuild our families. I hope its importance lies in that message. If there’s ever a kid reading who feels he’s inherited some sort of failure, I hope this book does something to dispel that myth.

Your family is a nightmare: addicts, abusers, losers, but here and there a tender streak. And yet you write them with such clarity and love. How do you forgive what has been done to you, and then spend so much time rendering it into prose?

I think it starts with forgiveness. I don’t believe you can really write about anything clearly until you’ve moved past it and accepted it. The people I write about experienced tremendous loss that led to incomprehensible amounts of drinking and drug abuse. I’ve heard it said that people who fall into drug addiction want to feel like they are loved. I could understand that. When my mother would scream her drunken tirades, I remember, even as a kid, knowing her anger was a manifestation of her sadness. I think it’s important to see the people you write about with love and compassion to reach some greater truth.

What are your thoughts now about the meaning of family—and as a gay man, how do you define, or would like to create, family?

For me, a family is a thing you earn. I can’t discount the importance of blood, and those irreplaceable bonds I have with my mother, but I wanted to build a family of people whose love I’ve earned with time and patience and respect, which can sometimes be stronger than a blood bond.

How did you reject and avoid a life of addiction? Especially when it’s so easy to fall into as a gay person with social rituals involving alcohol and sometimes drugs.

To be honest, I don’t really know. I imagine it was part survival, part fate. I never had any desire to drink. Not even when it was the coolest thing in the world for a high school kid. It never appealed to me. And I was willing to lose every friend I had over that decision. It was something that devastated my family and I couldn’t find the fun it, or the escape in it.

But, later in my life, I fell in love with a boy, a drug addict, and my unhealthy love for him became a sort of addiction of its own, and I realized addictions can shape shift and reappear in ways you may have never expected. I never touched a drug, but I have struggled with the concept. I think it’s important to acknowledge that it’s a part of you, and stay cognizant of the fact that it may find its way back into your life someday, and you need to not be afraid and be ready to face it when it does.

Your love for your little dog if often the only ray of sunshine in the book and gets you through a number of tragedies. Many gays and lesbians have a similar connection with animals. Can you tell me more about animals as family, and is there any special pup in your life right now?

There is an innocence to animals, an unconditional love, and I think we all need that in some form. Often, our animals will love us more than we might deserve. Even if we’re in the wrong, they’re always there. I experienced a lot of loneliness growing up, and I think there is a shared loneliness among gay people growing up, and animals can be a respite from that. They love you in a way you wish others would, and they don’t need society or a court or a law to tell them it’s OK before they do it.

My mother has two precious dogs — Gracie and George — and I’m the big brother, so for now, they are my pups, too. And they love my mother in that way I was describing. They don’t really know or care if she’s right or wrong, good or bad. They just know love, and I’m glad she’s found that in them.

In spite of all that happens to you in the book, including abuse, homelessness, and constant disruptions to your schooling, you pursue an education and you excel. You have core of pride in yourself. What kept you going?

On some level, I suppose I had some intuition that there was a better life out there. I have this memory of my father: He was 80-years-old, dirt broke, and living in a basement apartment, not sure if he’d ever see my brother and me again. And a friend asked him to make a list of things worth living for. He came up with a list of three things: Peaches, milkshakes, and The Sopranos. Sometimes, you just need the smallest things to keep you going. I think I inherited that kind of hope from him.

He enjoyed life, even if the only pleasure he could find was in a milkshake. I grew up around people who didn’t believe tomorrow was worth living for, and I had to learn from those mistakes, and decide that it was. Some people thought I could write well, and I thought that was worth fighting for. And then there are those moments when I feel like I just got lucky. I think, sometimes, that happens, too.

Many gays and lesbians escape into movies, music, theater, drag, etc. to achieve an alternate reality that their actual life doesn’t give them…for you it was Justin Timberlake and Roger Ebert! In fact, these connections provide the book with its biggest surprises and humorous encounters. Are you still a dreamer?

I don’t think I could ever lose the dreamer part of myself. I often think people limit themselves with what they think is realistic. Life is strange and sometimes incomprehensible, and my story, like so many others, is full of tragic loss. But some unbelievable miracles happen, too. And those miracles have kept me believing that you really just never know.

Sometimes lesbians feel that gay white men, of which you are one, are a privileged group—wealthy, powerful, at the top of the LGBT totem pole… Is this fair? What thoughts do you have about our community’s current discussions over privilege and exclusion?

I’ve always felt class does more to divide us than race or sexuality. Perhaps that’s because of the way I grew up. I was white and gay but because we were lower class, I was nobody. I knew lesbians and blacks kids, trans-people, and we all had one thing in common: we were all struggling. I saw the struggle before I saw their skin color or their sexuality. We related because of our shared experience.

No, not all gay white men grow up privileged. I’m actually surprised to hear that’s a common thought because the opposite has been so prevalent in my experience. As for exclusion within our community, I think it’s a very real issue, and one that all groups have been guilty of. Everybody makes their assumptions, and those assumptions keep the doors closed to one another. But I think anytime you group people together like that, you miss out on something extraordinary.

The portrait of your mother is truly agonizing–her alcoholism and her homophobia are severe, any sense of safety with her must’ve been tenuous. What advice do you have for mothers who might feel hostile towards their children’s identities, whether that be gay, trans, genderqueer, or questioning?

The portrait of your mother is truly agonizing–her alcoholism and her homophobia are severe, any sense of safety with her must’ve been tenuous. What advice do you have for mothers who might feel hostile towards their children’s identities, whether that be gay, trans, genderqueer, or questioning?

There are moments in the book when my mother goes off on these drunken, verbal tirades, and really no one is safe, and homosexual derogations do get flung. But when I came out later in life, she couldn’t have been more accepting. Sometimes I think it’s because we had so many other problems to deal with, my being gay barely registered. She’s met my boyfriends, she’s bought them Easter baskets, she’s invited them into her home. Her words, to me, were more a way of causing pain equal to the pain she felt, but it’s hard for me to know how much truth was behind them.

But what mother’s need to know is that they are everything to their children and their words and actions loom so very large. The hostility they feel toward their child’s identity will echo for a lifetime and will be present in every relationship that child has. I think mother’s need to understand just how powerful they are, and to be responsible with that power, use it to love and to teach. I’m not suggesting there’s a way to be a perfect parent, but at the end of the day, I can say, my mother wasn’t perfect, but I know she loved me, and that’s important.

I think children will always use their adult relationships to mimic that first one, the one with mom, and there’s something strangely endearing about that. There will always be something to heal.

And what a character she is! If The Autumn Balloon were to be made into a movie, which actress would you like to play her?

My mother recently asked if I could ask Melissa McCarthy to play her, so I’ll go along with those wishes.

Who are your favorite authors and do you feel that “Gay & Lesbian” should be a category of books or literature?

I’ve admired poets like Stephen Dunn, Ted Kooser, novelists like Marilynne Robinson and Margaret Atwood, memoirists and essayists like Mary Karr and Poe Ballantine, critics like Roger Ebert. But sometimes I’ll stumble upon something else, a judge’s opinion, for example, and the judge will have written with such insight and clarity, and I’ll realize writing inspirations can come from anywhere.

I think “Gay & Lesbian” categories have their place but are a bit misused. So often, gay authors or books with gay protagonists that deal with a myriad of complex issues are unfairly reduced to “gay and lesbian” when in fact they are more than stories of sexuality. I think as time goes by and gay issues become more widely accepted as human issues, those classifications will become clearer.

What are your plans for Pride?

I will be in the Dominican Republic for Pride, my fist time to the country, and very excited.