When I was a closeted young adult, I would sometimes wear dresses, not high femme fashion like a Victorian dress, but dresses nonetheless, to throw the scent off people wondering if I was gay. Shockingly, when I have worn dresses, it often worked as many people assumed—even with my big butch body—I was straight. Which, at the time, was what I needed. There’s a distinction, even today in our culture, between male and female fashion and appearance. Any deviance from this norm might have consequences ranging from mild harassment to overt hostility.

Even before Stonewall in 1969, there was a strong butch/femme dichotomy in underground bars in the United States that mimicked the heteronormative male/female gender roles.

The more traditional description of a butch lesbian is someone whose gender expression (appearance, dress, and behavior) is more masculine and whose gender identity is female. This is a simple and limited description, as butch identity can be more fluid.

I’ve known many self-proclaimed femme lesbians over the years who wore dresses but were more butch in behavior than I ever could be. Even so, there are still plenty of gatekeepers who think the true and purest definition of butch is more uniform in appearance and behavior. But how much does our outward appearance dictate our gender identity as butch, femme, non-binary, etc.?

In the movie, Victor Victoria, part of the humorous storyline is about a woman dressing like a man dressing like a woman. As a butch lesbian, I dress like a man, but was pressured to dress like a woman, but ultimately, dress like a man. So you might be asking, or laughing, looking at these images of such a masculine-looking female dressed in an 1880s Victorian-styled dress, “Why?” Why would I, a self-proclaimed, masc-presenting woman, choose to not only put on this dress but also take photographs? Did I lose a bet? I’m clearly past the point of feeling pressured to dress in women’s clothing. I was, however, curious if wearing two types of clothing at opposite ends of the fashion spectrum would change how I identify. Would I feel less butch or possibly more femme?

Culturally, clothing and gender expression can represent and mean different things. A kilt for example, a type of clothing similar in appearance to skirts, worn by a bearded, muscular Scottish man, will come across as tough and masculine. Think Braveheart. Imagine Mel Gibson walking down the street in a kilt. Now imagine him walking down the street in a designer sundress.

With the movie Victor/Victoria on my mind, it seemed fitting for this fashion experiment to choose something more formal from that time period. Victorian dresses are historically exceedingly luxurious yet restrictive, almost oppressive in the way they’re so tightly bound and laced. A type of dress that would clearly alter my appearance. At the opposite end of a Victorian dress was a tuxedo. Wearing both wasn’t exactly comfortable, but the tuxedo-like fashion did seem like something I’d wear today. The dress, however, felt like a costume. I mean, it was a costume. Unless I was heading for some sort of femme fatale Bridgerton party, Victorian-era dresses aren’t exactly mainstream.

When I finished putting on the dress (it took a while), I felt like I was role-playing a Lady of the House, fanning my face while trying to assertively sashay through the gardens (trying being the operative word in that sentence). Interestingly, women in this time period didn’t actually have power. But pretending to play such a hyper-feminine role gave rise to a more subtle influential shift in power. As if I’d been cast to play Penelope on Bridgerton and covertly worked behind the scenes to manipulate my world. It felt more like an intellectual type of empowerment. The tux seemed rather dull and common. A bit fancier than most suits I’d wear, but nothing unusual in my mannerisms. Since I’ve worn masculine clothing for years, I was used to the confidence and boldness they exude. I did wonder if there was a correlation between more stereotypical masculine clothing and an increase in bravado. Imagine if I’d chosen a construction worker’s apparel.

I dressed as Marie Antoinette one Halloween, complete with a two-foot-tall wig, makeup, and a cage crinoline underneath that made entering doorways impossible. Similarly to the photo shoot dress, I felt weirdly empowered. Granted, I was playing a queen as I paraded about like a mediocre cisgender white man in America, full of entitlement and confidence.

When I was a bridesmaid for my sister’s wedding years ago, I had to wear a pink chiffon taffeta dress with matching three-inch pink heels! I wobbled down the aisle, praying I wouldn’t break an ankle, dressed as a six-foot-tall ball of cotton candy. My ability to move with ease felt constricted not only because of the dress design itself but by our culture’s unsaid assumptions of appropriate female behavior while wearing it, i.e., modest, small, and compliant.

Clothing makes us feel different to varying degrees. Whether it’s a costume party or daily life, we all play roles, though our gender expression can shift, sometimes to the extreme. Dressing up in costume is about having fun and pretending to be someone we are not. As long as society perceives that someone is wearing a “costume,” it’s acceptable to appear and behave differently. But if it’s not a costume, then it can be problematic. Our culture, in particular, tends to have a more rigid, narrow definition of what’s acceptable gender expression for certain groups of people. Image a macho male football player wearing a female cheerleader outfit, prancing around for Halloween. It would be funny to a lot of people. If he decided to don that same outfit in daily life, however, he’s suddenly labeled a fairy, queer or sissy boy. It’s only humorous if he’s playing a part, but offensive if he really is the part.

Some progress over the years: The clothing that people wear, especially for women, has diversified and expanded, breaking free of societal expectations. In my younger years as an athlete, on game day, my coaches, all former athletes themselves, who I never saw out of sweatsuits (think GLEE’s Sue Sylvester played by Jane Lynch), would, without exception, all wear dresses and skirts. I’d watch them lumber into the gym, like masculine female athletes, forced to wear highly feminine attire, and each time they looked like, well… masculine female athletes wearing highly feminine attire. I often laughed, thinking, “Who is making you wear these ill-fitting dresses, and why?” They looked so absurd and uncomfortable as they sat awk- wardly, legs spread, yelling and screaming at us from the bench.

Butch is not always the same thing as masculinity or ‘masc.’ A person can be masculine in their gender expression but not consider themselves butch. It’s all contextual.

Many self-proclaimed butch lesbians fall into the more traditional definition of gender expression, i.e., short hair and male clothing, saying they feel more comfortable dressed that way. As if their inside appropriately matches their outside. Yet there are others who don’t feel an external masculine appearance is a requirement to feel still butch. It’s important to understand the term butch is not exclusive to butch lesbians. It’s used by trans-women, trans-men, non-binary people, queers and even cis-women.

Butch is not always the same thing as masculinity or “masc.” A person can be masculine in their gender expression but not consider themselves butch. It’s all contextual. Think of drag queens. Certain groups of people lose their shit if they see a drag queen in high heels, makeup, a wig, and dress, sashaying down the street or, heaven forbid, reading to kids in a library. Suddenly, it’s blasphemous and political. But that same drag queen, walking down the street in jeans and a t-shirt, gets little to no response. Well, I suppose if they’re properly sashaying, they might be noticed. But aside from more effeminate behavior, it’s the same person.

Being butch isn’t necessarily about clothing. It’s more of a conscious activity, a lifestyle, and a confident energy I carry. It’s an attitude that can sometimes shift depending on my mood. My internal and external feeling of being a butch lesbian also doesn’t have to mirror and imitate male behavior. It can simultaneously be feminine and masculine. Whether my external comfort lies in more masculine attire or, every once in a while, slightly feminine, butch is my innate identity.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

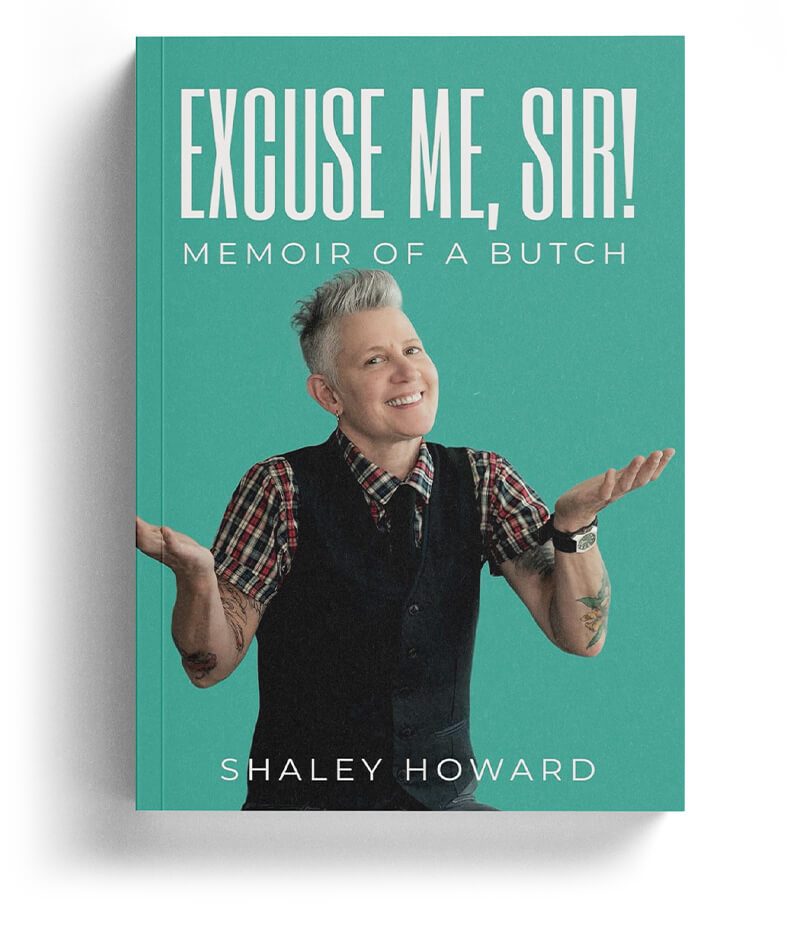

Shaley Howard is the author of the recently released book Excuse Me, Sir! Memoir of a Butch, which received the IPPY Silver Award for excellence in 2024. She’s a small-business owner and an award-winning activist in Portland, Oregon.