When I look back at my time as editor-in-chief of Curve from 2010 to 2020, one of the many pleasures of the job was mentoring writers. By Merryn Johns.

Prior to Curve I had worked for a decade as an adjunct professor in the liberal arts, teaching university students from freshman to postgraduate level. The aspect of academia I relished most was teaching. It was richly rewarding to nurture emerging voices and even to help shape mature ones. The majority of my students were women, many of them LGBTQ, and I supervised and graded their term papers, dissertations and creative coursework in a variety of subjects during the heyday of third-wave feminism, queer theory, and gender theory. That experience came in handy for my role at Curve magazine.

While being an editor-in-chief involved a lot of writing, chasing cover stories, and meeting budget, I spent as much time developing the voices and talents of queer women writers within the pages of Curve as I did creating content for our readers that was fresh and compelling.

Every month it was challenging for our magazine to meet budget, and if you can’t pay mainstream media rates per word, you often work with writers who are just starting out. Paying people is important but we also tried to offer our contributors additional riches. Curve always offered its writers a home, a family, a fellowship, and the knowledge that social justice and governance were baked into the content creation. And as a personal touch I often supported writers’ passion projects and side hustles, turning up at their music or comedy gigs or spruiking their latest blog, zine, or novel.

I worked with and mentored some incredible writers at Curve, and one standout voice in our sisterhood of ink was Lyndsey D’Arcangelo. Lyndsey was an out lesbian with a background in mainstream newspaper journalism in her hometown of Buffalo, NY, who actually saw writing for Curve as a step up. She had the qualities all editors need: she was rational, reliable, and responsive. She wanted to tell stories within the framework of the facts: the who, what, why, where, and when that are drummed into J-school students. Except Lyndsey, like myself, never studied journalism. She, like me, came to it through creative writing and identified its power to amplify underrepresented voices and speak truth to power.

While Lyndsey came to Curve as a culture writer with one YA novel about Emily Dickinson under her belt, I noticed that whenever she filed on sports her copy was especially inspired. Her prose was punchy and wise, and I felt invested in her almost gladiatorial portrayal of queer women in competitive sports. There was what happened during the game or match, and there was what happened courtside and in the wider culture around a player or coach’s gender, race or sexual orientation. I started to assign Lyndsey all the sports stories whenever they came my way. And that was quite often.

Suddenly, Lyndsey had a ‘beat,’ or specialized area, like an old-time reporter — but in new times for queer women. Following Sheryl Swoopes coming out in 2005, it seemed every other month another high-profile athlete found the courage to stand up for our community. Competitive sports became an arena that was vitally important in the lesbian visibility wars at the time. While musicians and comics, from Ellen DeGeneres to Melissa Etheridge, blazed a trail for us, before them were athletes like Billie Jean King and Martina Navratilova who both came out in 1981 and almost lost everything in the process.

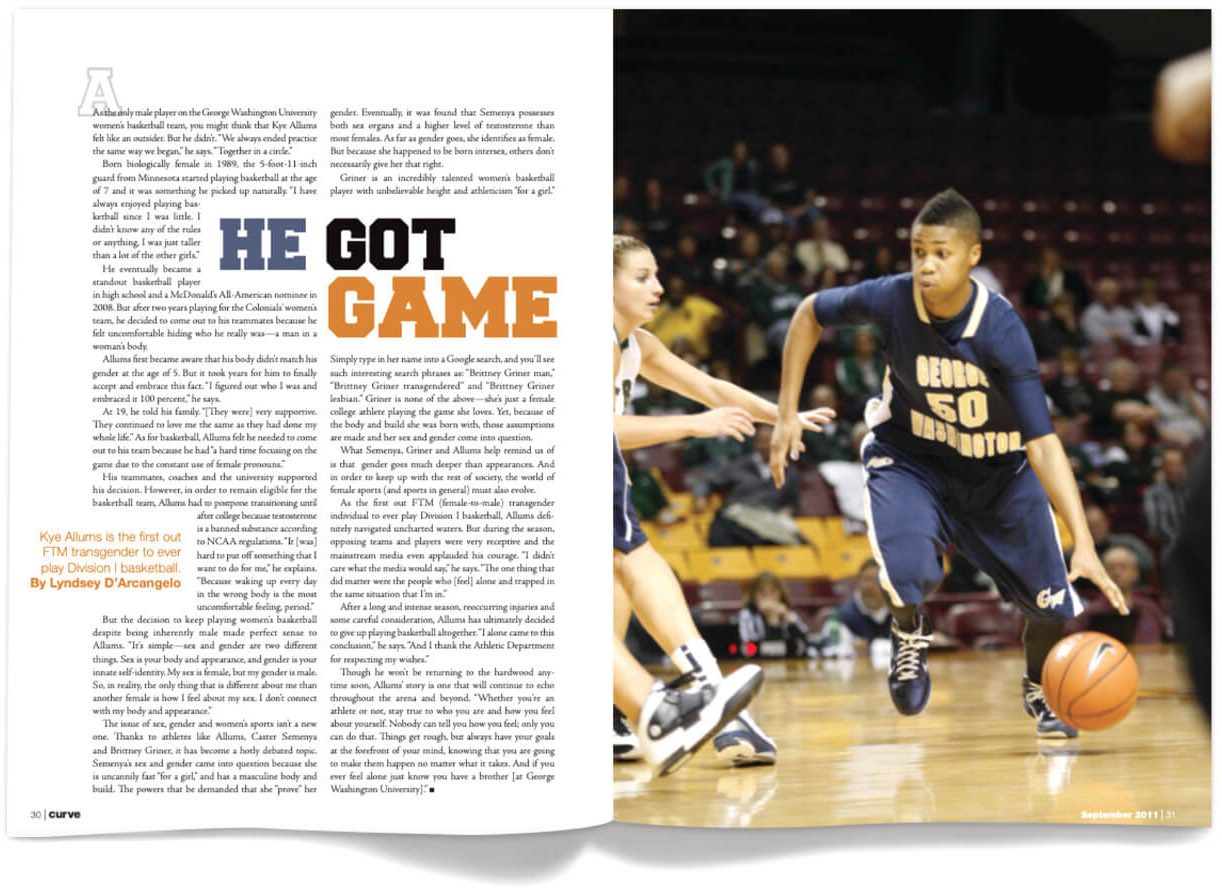

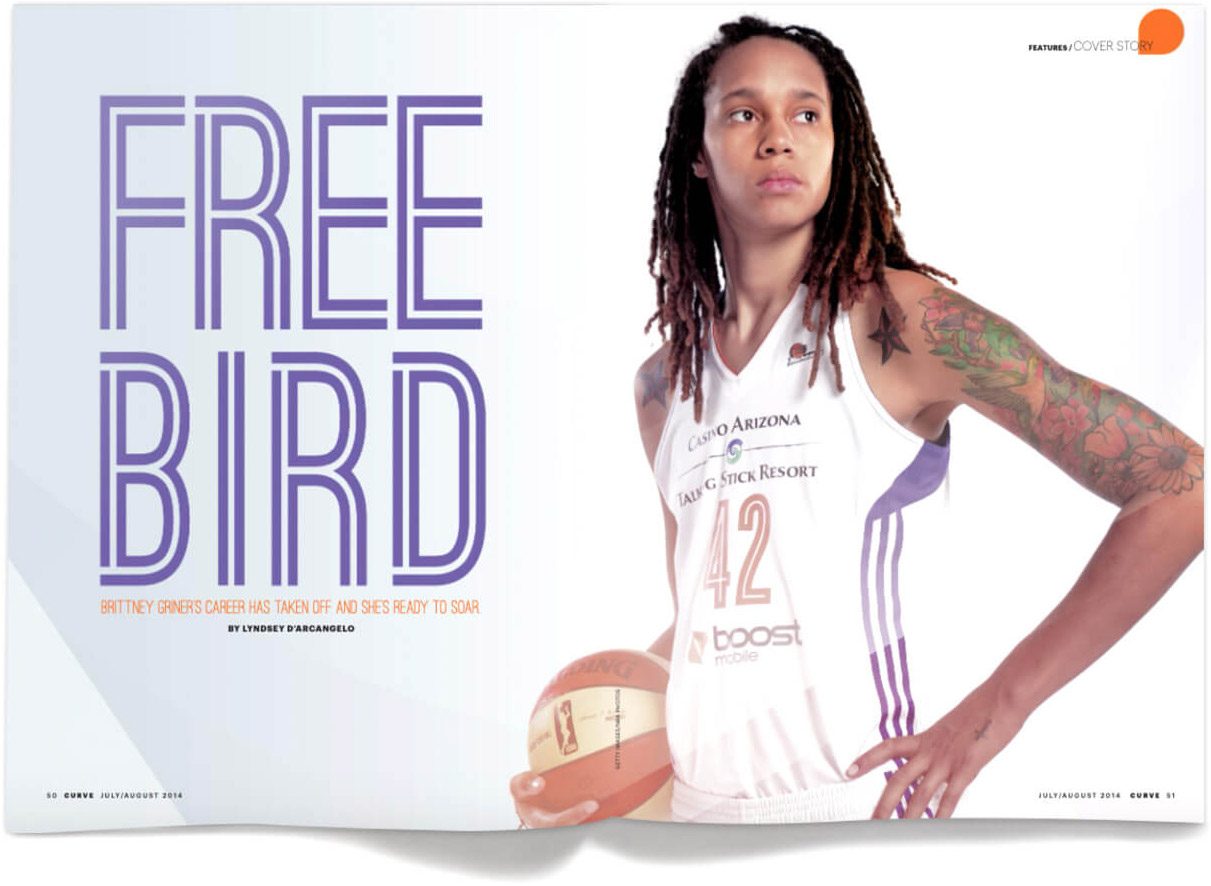

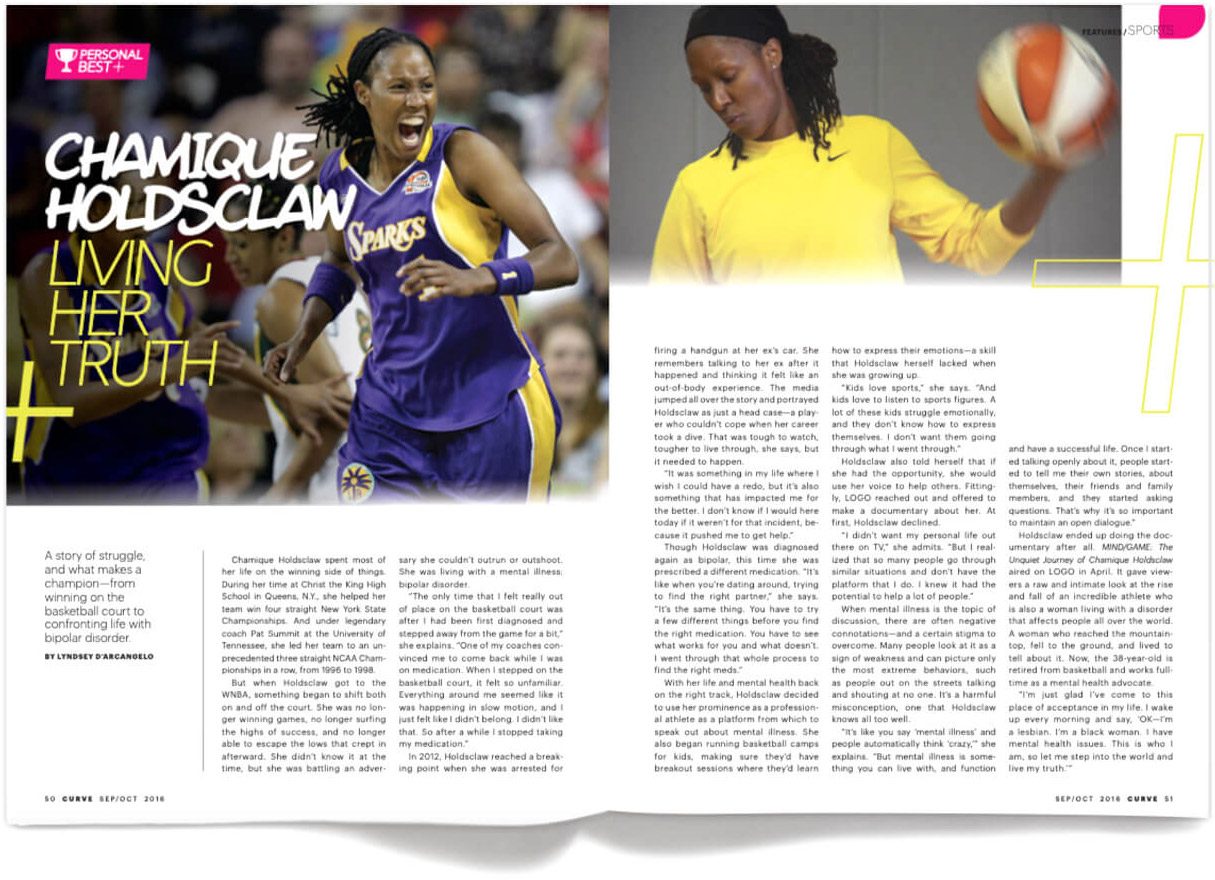

Competitive sports have always been an arena of lesbian excellence but very few people knew how to write about it. As the best-known lesbian magazine in the world, Curve needed an excellent sports writer. I was more than confident to assign Lyndsey stories on out athletic legends: Megan Rapinoe, Britney Griner, Stefy Blau, Casey Legler, Martina Navratilova, Layshia Clarendon, Chamique Holdsclaw, and Kyle Allums — the first out transgender FTM male to play Division I basketball — to name but a few.

Today, Lyndsey is the author of six books and writes about women’s college basketball and the WNBA for Just Women’s Sports and The Athletic. In 2020 she launched Courtside, a series featuring conversations with some of the greatest players in WNBA history as well as rookies, vets and All-Stars in the league today. In 2018 she received a Notable Mention in the 2018 Best American Sports Writing anthology for her essay My Father, President Donald J. Trump and the Buffalo Bills. She’s written for Deadspin, The Ringer, ESPN/espnW.com, Teen Vogue, Them, The Guardian, Allure, The Huffington Post, Thefootballgirl.com, NBC OUT, The Buffalo News/BNBlitz.com, Buffalo Magazine, Gay Parent Magazine, and more. Her book Hail Mary: The Rise and Fall of the National Women’s Football League is out on November 2.

I caught up with Lyndsey to ask her how she looks back on her time working with Curve:

Do you remember your first-ever encounter with Curve?

LD: I saw it at a friend’s house. It was in the early 2000s, maybe 2003/4. I was 24 or around there and I was completely enamored with it. I had just started my writing career and was working at the Buffalo News as a copywriter. My friend who subscribed to the magazine said, “You should write for them.” My immediate response was, “I could never write for them. It’s a national magazine!” But a seed had been planted and it became a goal publication of mine after that.

When did you first write for Curve?

LD: I had eventually pitched a few smaller pieces to Curve via Rachel Shatto, who was an editor there. They were back of the magazine things — a short book review, a blurb about a fun new L Word-themed podcast, stuff like that. Little by little, I started pitching bigger stories. Then, I started pitching directly to editor-in-chief Diane Anderson-Minshall and she began assigning me features. Occasionally, I’d pitch a story about a lesbian athlete. Then in 2010 when you took over as editor-in-chief we talked on the phone and you said you wanted to expand the sports coverage of the magazine and asked if I would be the go-to person for that. I jumped at the chance.

I thought your sports writing was very strong. Do you remember the first time you thought you would be good at it?

LD: I didn’t set out to become a sportswriter (though my mother had said since I was a teenager that I’d make a great one). And really, I have you to thank for that. I’ve always been a sports fan and I’ve always been good at writing, but I never thought to put the two together until I started writing feature profiles and cover stories for Curve. It just took off from there and I never looked back. My work for you and for Curve set me on a path to where I am today and I am so grateful for that — to go from not even believing I could write for a national magazine to getting my first cover story? That was a trip.

You did some great cover stories on some great out lesbian athletes: Britney Griner and Megan Rapinoe spring to mind. Any favorites in your long list?

LD: Griner, Rapinoe, I still have those magazines in my office. I’ve written about the US Soccer Team, the WNBA, women’s football, motocross, Martina Navratilova, a baseball player from the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League in the 1920s who was closeted at the time, and lots more. I got to cover so many different sports topics as well as interact with a variety of lesbian athletes. It was awesome.

Why do you think queer women succeed in competitive sports?

LD: I think queer women aren’t afraid to be who they are and don’t care about fitting into a particular box that society dictates for us. And for many queer women, being masculine and athletic is natural to our existence and when it comes to sports, that’s an asset. I think sports and teams in general are safe spaces for queer folks, because being athletic for women was already subverting societal norms. I think a lot of lesbians go into sports for that reason, but also those of us who are/feel more masculine had a way to express it that was deemed acceptable on the sports field. I know that I always felt more comfortable in my own skin when I was playing basketball, soccer, football — any sport, really — than I did anywhere else growing up and until I came out (even after coming out, for a time).

How did the editorial process at Curve help shape your voice as a writer? Was there any particular moment when you felt you were growing or honing your voice?

LD: I think I got better and better with each story that I wrote. Again, I started out with small assignments. Then eventually, cover stories. Rachel was amazing, Diane was great, too. The moment for me was working with you, because you really helped me hone in on my niche, on where I was the strongest. Fusing sports and my ability to write a great profile was the key. And then I remember it got to the point where you would hit me up with ideas and say, “Do you want to write about this?” I also remember being listed consistently in the magazine in the staff section as Sports Editor after a while. That meant so much to me. It was confirmation that I had evolved as a writer in a big way.

Of course, you have written on many subjects outside of sports, and you were an established YA writer when you came to Curve. Tell me, how do you think journalism helps writers, and conversely, how does creative writing help journalists?

LD: I think they are two sides of the same coin. When I embarked on my current nonfiction book, Hail Mary, that’s coming out in November, it never daunted me. Because it’s basically a really, really, really long feature story. You interview, report, research, take notes and then write. It just happens to be 80,000 words instead of 2,000.

I can only speak for myself, but I’ve learned so much about writing through being a journalist. I was not “classically” trained. I went to school for English/Creative Writing. I took one journalism class in college and I got a C in it. I basically had a real world education that started at the Buffalo News and continued when I left to freelance full time. I learned from a variety of different editors from different publications. Curve was my main classroom though. I wouldn’t be where I am today if I had never pitched that first little article to Curve.

We have never met and yet we worked well long-distance before that was normal. What would you say is key to being a freelancer and maintaining a virtual relationship with your editor?

LD: I think you and I always clicked. We’ve never met, but I consider you a mentor and a friend. For me, the key was that you were willing to work with me and figure out my strengths, then give me assignments that matched my strengths. I don’t think people realize how important that is for an editor to do. It’s not just about cleaning up a draft and correcting errors. I’ve worked with some really great editors during my career and also some horrible ones. You can tell the difference. Working with a great editor makes all the difference in the world. And you were/are a great editor.

Favorite Curve memory, as writer or reader?

LD: It’s funny looking back now, how Curve played such a huge role in my career. I always got a copy of the magazine in my mailbox. But my favorite thing would be going to Barnes & Noble after the new issue dropped and seeing it there on the shelves. I’d buy it, too. When my first cover story came out, I was so damn proud. You don’t forget your first!