On September 12th, I was joined in the proverbial Zoom room by Katie Barnes, Helen Santoro and Yvonne Marquez for a breakout session at NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists’ 2021 conference. The session, entitled “Storytelling at Our Intersections,” brought us together for only the second time since a rapid-fire introduction earlier that week. I was nervous.

I asked each of them to consider topics of some depth: how we carry our own identities, stories from our communities, and lessons we’ve learned as we build our careers. I wondered how we’d connect to each other, but there was no need to. Each of these journalists came to our conversation with a vulnerability and wisdom that made Jen, Franco and I beam.

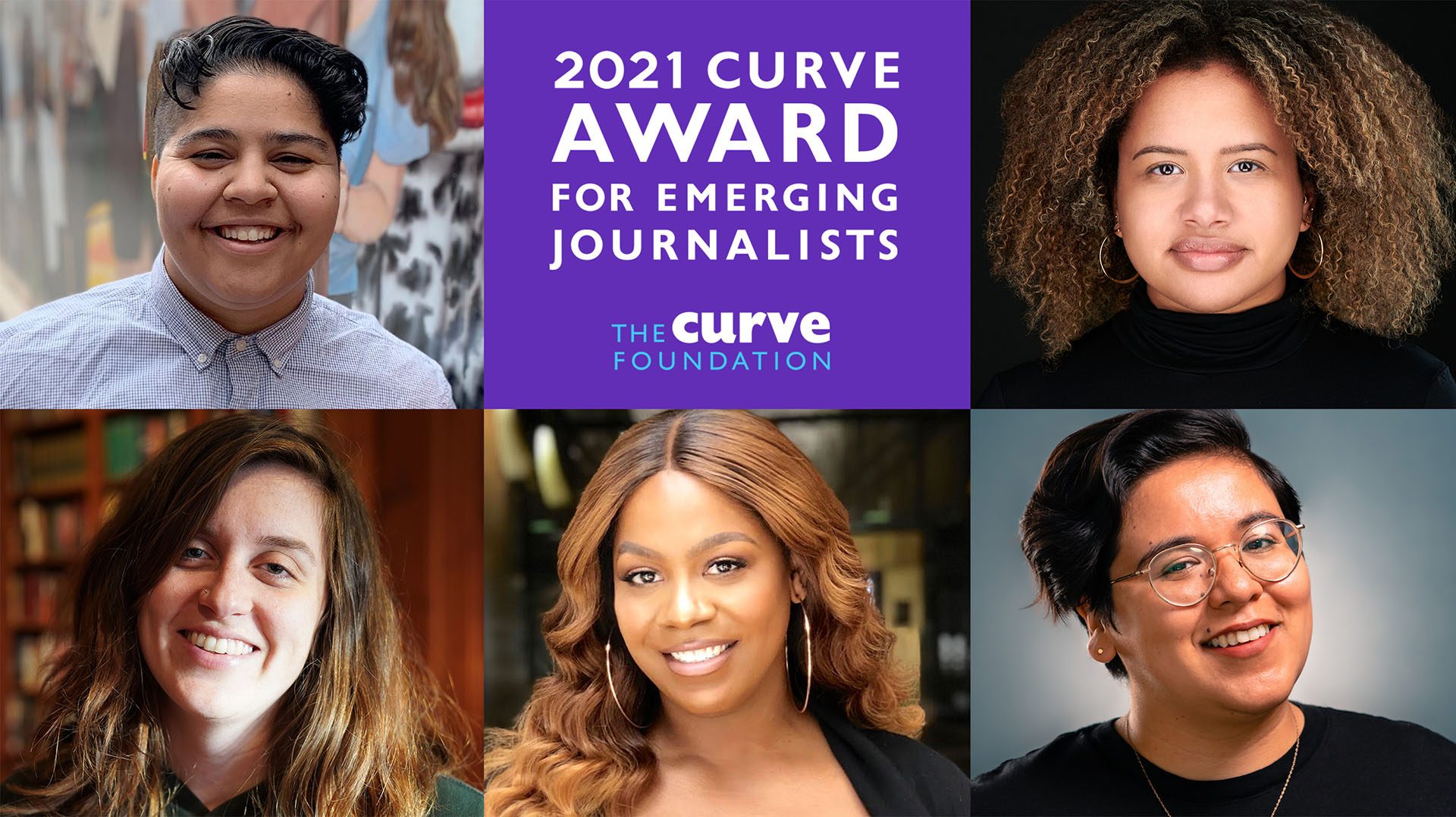

Our hopes for the Curve Award were that it would begin a conversation between the Curve Foundation and the leaders that need resources to tell lesbian and queer stories of the future. I had no idea that the award winners would also come to this cohort with such depth of vision, experience and affinity for our community.

When asked about stories from underrepresented geographies, each person brought vivid images from places with rich, but invisible, lesbian and queer histories. We hope that you find them as inspiring as we did.

Jasmine

I want to highlight something that you said, just because this is important in the context of Curve. I don’t think that all stories about our community have to be human rights stories. In fact, stories about our joy, and our everyday nuance, and our humanity are just as important. I think the magazine was very adamant about that as well. Martina Navratilova was on the cover of Curve in the ‘90s. That’s very much how the magazine has always held itself.

I’ve heard, as I’ve sat through this conference, that there need to be more spaces for joy – for stories about things that are solutions focused. So I just want to highlight that they’re not lesser than, they’re as important, and we hope that we can keep supporting you to tell those stories.

Okay, so my next question is a regional one, because I think all of us are coming from some underrepresented geographic regions. And I know, as journalists, sometimes that can be a challenge, but also an opportunity.

And so my question to you–it can be your home region, it can be the region you’re in now–what do we need to hear from some of these underrepresented regions in the queer experience? Southern queer folks or folks from rural communities, outside of major news cycles or regions? What are we not hearing? What do we need to know?

Helen

I’d be happy to kick it off. I live in a really rural part of Colorado. You leave Gunnison, and it’s, I think, an hour and a half of just high desert sagebrush until the next anything.

There’s such a news desert in general in rural America, and that’s something I always try to address. But going back to a point made earlier about the same stories being told over and over, the common story you’re told about the queer experience in rural America is that it’s awful. And that it’s terrible, and it’s awful, and we’re discriminated against.

And those are true things. Those are true experiences in a lot of cases, but not all cases. Gunnison, Colorado, shockingly, has an amazing queer community. That’s literally one of the reasons, if not the reason, my wife and I decided to stay and make a life here. Those stories are definitely not told enough, and that’s something that I’m trying to bring to the table.

One of the stories that I want either my wife or myself, or someone, to write is the fact that she just came back this morning from skeet shooting. That’s when the clay pigeon goes up, and you shoot it with a shotgun. She’s a trans woman from the North Shore of Boston, and she has created this incredible community with ranchers who skeet shoot three times a week!

I have never heard this story before! We need to talk about these bridges. And every time I mention that to people, they’re like, “What? How does that exist?” I really think that that’s an underrepresented experience of rural queer people that I’m hoping to bring to the table more in the stories that I pitch.

Jasmine

Thank you. Katie, I think I saw you come off mute.

Katie

Yeah – but mostly, to kind of say the same thing.

I grew up in rural Indiana, and my mother – well, both my parents but my mother specifically – are very religious people. I grew up going to church. And that’s always been a very positive place for me.

In fact, when I would come home from college, you know, I would come home to this church full of queer and trans people in the middle of nowhere, Indiana. I think that would surprise folks. My mom, who has lived in this tiny town for 30 years, had a trans pastor for a big chunk of that. Those kinds of stories, the way that queer folks connect, in general, are really important. And that connection looks different in different places.

I think for so long (and I say this with absolutely no potshots) the It Gets Better narrative – like, it gets better once you get out – that kind of flattening of the narrative has really driven the way that stories are framed about queer and trans folks. Not in New York and LA, or DC, right, and it’s a very urban coastal driven experience.

You know, I think that’s something that I didn’t even really quite understand, in the same way, until I moved to the northeast. There are a lot of things that are great about living in the northeast. It’s very integrated in many respects. Nobody cares that I’m queer or trans, so consequently, it’s also kind of hard to find people who are queer and trans. There’s a certain reality that oppression creates community, right?

And so when you are experiencing less oppression, that integration and diasporic experience is allowed to happen. Which, again, great – no complaints! But it’s a different experience and I feel like one has very clearly been elevated over another. And in fact, we know that these things aren’t that narratively simplistic. We have much more complex and nuanced stories, and the experiences of queer and trans folks vary so much across the country. We should be more invested in telling those stories.

So basically, just a really long answer to say – yes, I cosign.

Jasmine

I love that we’re going for nuance Katie, so A+ on the assignment. I want to just underscore that as someone who has lived in many different places, the most exciting, and inclusive, queer community I was in in was a black lesbian community in Dallas, Texas. I had a blast.

It was great. Best time ever.

So, speaking of Dallas, Texas – Yvonne! As someone who represents some underrepresented regions, but is now in arguably the largest news market in the world, what’s going on?

Yvonne

Yeah, I agree with what Helen and Katie have said.

I just moved to Brooklyn, maybe a month ago, and people are like, “Oh, you’re from Texas, aren’t you so glad you’re here?” And I’m like, I take a little bit of offense to that. Because I love Texans, I love the people. I just don’t like our government, you know what I mean?

The thing is that – what I’ve seen in Texas – is that there are so many queer and trans people leading movements, and organizations who are fighting for change. I think that is definitely something that’s underrepresented in stories.

I think people don’t know that queer and trans people are leading the fight for abortion in Texas, you know, for black lives and abolition. Those are the people who are doing a lot of work. And I don’t think that is highlighted enough.

You know, that’s something that, people on the coasts like to lump Texans in with Texas. “You’re conservative. You’re Republican. You’re like this or that.” But, you know, it’s not true. There are some very radical people in Texas, just because they have to fight and imagine further than what is available, and come up with new ideas to survive and help their communities out.

I just think that’s really awesome and really cool. And that’s something I’ve been trying to do and write about the folks that I come in contact with, and who are part of my community as well.