Lesbian photography is one of the championed causes of Curve. But what are lesbian images, what makes a lesbian photographer, and what are some of the issues they face? Here, Merryn Johns is in conversation with lesbian visual artist Jeanette Spicer on the eve of the release of her new book of photography, To the Ends of the Earth.

All photos by Jeanette Spicer

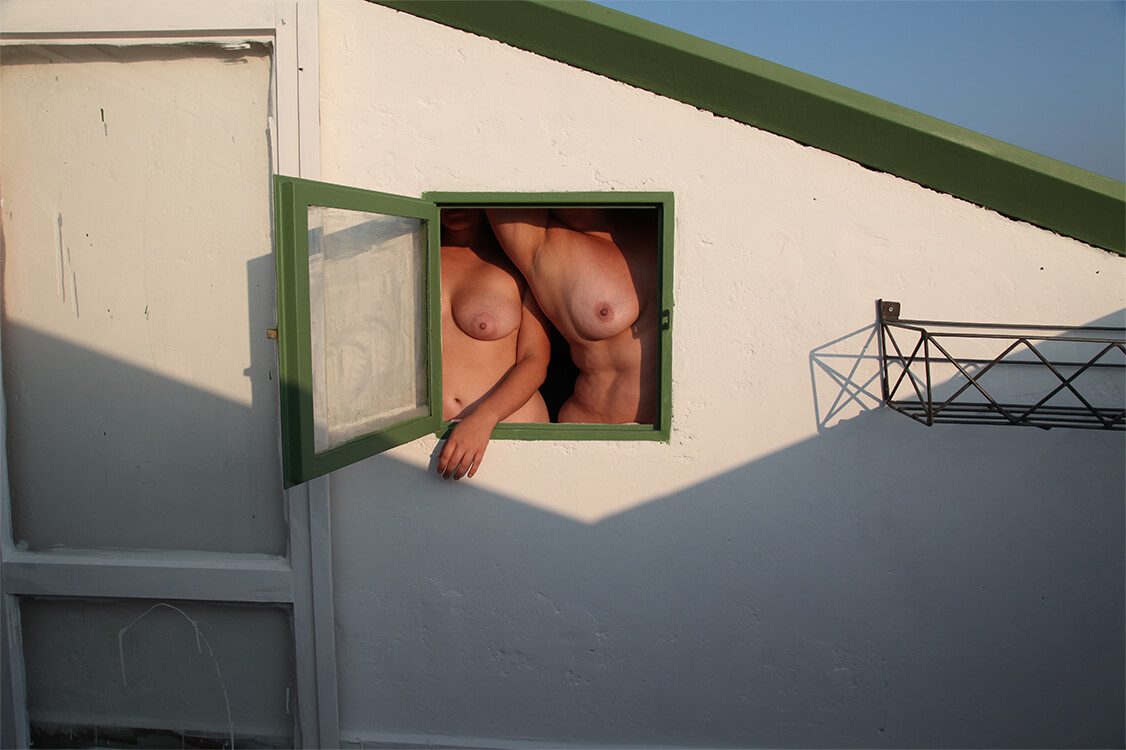

Among many other things, Jeanette Spicer is one of the publisher-editors of fellow lesbian publication, WMN zine, which Curve featured last year. In addition to her efforts at WMN, Spicer is a visual artist and editorial photographer whose work has been featured in the New York Times, New York Magazine, and the New Yorker. The 55 striking images in her new book are deeply personal and yet consolidate the lesbian gaze with their exploration of identity and desire-mothers, girlfriends, other women. In one of the images, Spicer’s girlfriend is depicted in silhouette beneath a portrait of her mother, naked, who gazes directly at the camera. All of the images in the book have layered significations around origins and sexuality. I wanted to find out more and had a few questions for Spicer.

Curve: Thank you for identifying as a lesbian-and the specificity of that. Can you tell me why that’s a more fitting word for you than ‘queer’?

JEANETTE SPICER: I didn’t have a choice, but you are welcome, ha! I watched Barbara Hammer give a talk about her work, her life and her lesbian identity shortly before her death. She spoke in depth about how she and her generation fought for the term ‘lesbian’, and how she used it with pride and dignity. At that time I identified as queer, but after hearing her speak, and realizing that lesbian does align with my values, sexual orientation and lifestyle, I had a responsibility to carry on the term and to keep it alive. For my personal sexual orientation, queer is broad and lesbian is specific, I like that it is very clear about who I am and what I am about. The term lesbian was an embarrassment when I was growing up, it was used as an insult, so using it now as an adult is very empowering for me. Each time I say it I feel more and more comfortable. It is also about pushing myself and learning and growing. I am always for the underdog!

As a lesbian image maker, who are your other role models and inspirations?

JEANETTE SPICER: Well, there are many lesbian

makers, but sadly a lot have been written out of, or never written into, history, so I did not have a plethora of lesbian makers that I looked up to. However, that has changed in the last five or so years once I realized this and made a concerted effort to do research. Barbara Hammer’s unique and confident way in which she navigated her sexuality, and lifestyle (meaning not remaining married to a man, traveling, unconventional ways of making money and living) was extremely unusual and frowned upon for her generation and her ability to push through that and build community and make work is an inspiration. I am also inspired by Deborah Bright, who has contributed greatly to the LGBTQ canon of art with her writing and her own art practices crossing over from painting to photography and back to painting. JEB (Joan E. Biren) and Tee Corinne for creating a space where women could go and learn about photography. The Ovulars which was held once a year I believe in the summer on land where the women would build darkrooms and living quarters where JEB and Corinne would teach women about photography. I still wonder if I could ever accomplish something like that, and look to them when I am feeling depleted or curious about how to build community. The way Corinne worked with effects in the darkroom and with her negatives to give the viewer a different way of seeing women, and our intimacy, is big for me right now.

I am always curious about how to ask the viewer to reconsider what they think they are looking at. For painting, I look at Emma Steinkraus, Louis Fratino, Elisabeth Glaessner, Alannah Farrell, among MANY others who work with the body. Also, Eva Hesse who while she had no visible bodies, her work feels very bodily to me. I am curious about material more and more.

Your book To the Ends of the Earth is one of the more effective bodies of work I have encountered that dismantles the male gaze and posits a lesbian gaze that is free from ‘male gaze fleas’, i.e. appropriated notions of identity and desire. As a visual person, and someone who has worked in magazines for 20 years, it took me so long to deprogram myself — because my entire education had been rooted in the concept of male genius, male desire, male desire appropriated by lesbians etc. What I encounter in your work is a complete refusal to enable the default position of the voyeur. It is something else entirely, and I wonder if that’s because while your figures are naked, ‘desire’ is a different concept here. Can you respond?

JEANETTE SPICER: I think what you say here is much better written than anything I could come up with, and very in line with what I try to do in my work, and ask of the viewer, too. I am delighted that you experience that in my work and can see where I try to dismantle my understanding of women, our experiences, and that they don’t always have to be by men and for men.

I am intrigued by your mother, her gaze, and what I’m sure she has been told are her beautiful eyes. What brief did you give her, how much direction, and how did she respond to the assignment?

JEANETTE SPICER: My mother was raised by a Sicilian first-generation American mother who was of the generation that was expected to create a better life for her parents, herself and an even better life for her children. Along with that, was a certain beauty standard and expectation that all women are conditioned to have, but was even more intense for her as she worked very hard to look ‘American’ and not Italian. She went as far as to have an extension shade put out on her little deck so that when she sat outside she could control how much shade or sun she got so she didn’t look ‘too dark’ AKA ‘too Italian’. This obsession with looks was passed down to my mother, of course, and while my mother has never said anything negative about my personal looks, I have known her to make comments about the looks of others, mostly from an observational perspective, and often about age. She is very concerned with how she looks and presents herself, but has never passed that on to me, but of course, I am influenced by it. When she is photographed she is very aware of me, but performs as unfazed, which I think results in her sometimes looking almost through me, or just off to the side. I give quite a bit of direction because my work is highly performative and constructed. She has been responding well, with a ton of patience, a constant flow of her time and interest in the work for the last 12 years. And yes, she has beautiful eyes! Thankfully I share some of those eyeballs, too!

In these photos your mother poses with you, and your girlfriend Sara, naked. How did you come out to your mother, and how did that feed into this project?

JEANETTE SPICER: I actually wrote to both of my parents (separately-they are divorced) in an email about my new girlfriend at the time. I was helping her move in, my mom was coming up to visit and I wanted to be open and honest. I really dislike that gay people have to ‘come out’ of hiding, it isn’t pleasant and it isn’t fair to have to hide such a huge part of yourself for so long. It does long-term damage that a lot of us are only just now unfolding and facing. My mother supports me in all aspects of my life, so this was not any different, but I do make an effort as I have gotten older to purposely (and I appreciate that you didn’t say this in your question) not say that my family, or anyone else, ‘accepts me’, because that positions that person above me, as if they are bestowing their acceptance onto me, and it creates an uneven power dynamic.

Regarding my being a lesbian and how that feeds into the project, it is the entire project. I think about how my mother sees and understands me as a lesbian, how I see and understand her, how she seems and understands my partner, and vice versa. How the viewer perhaps sees the three of us, and that it is unlikely that they view us as two lesbians and one straight mother, because of how we are conditioned to see through heteronortmative lenses. I am also interested in motherhood, in general, but as a lesbian, what it will be like, and how I will experience it, so photographing my own mother allows me to think through and consider how mistreated mothers are. They are pigeonholed into that role when mothers are in fact multi-faceted human beings with much more going on than having children.

Please tell me what the title of the book, To the Ends of the Earth, means to you.

JEANETTE SPICER: I found a book on the street right when I was doing research for the book in terms of digging more into motherhood, and thinking about titles, called, Mothers: An Essay on Love and Cruelty by Jacqueline Rose. The book basically discusses ancient, and contemporary ideas and histories about how all societies place their judgments, desires, wishes, thoughts pain and idealizations onto mothers. In one passage a woman had been separated from her son because of a war and she said she would, ‘go to the ends of the earth to find him.’ It gave me chills. This happens so often and in my privileged position it really made me realize that this is not a story, this is a fact that has happened thousands of times over. It made me think about how motherhood is primal for most, and that you would really do anything you possibly could for your child. It is also an open-ended title in that I feel this way towards those I am deeply close to, not just family, or a partner, but also friends. It is a way to speak about the ways in which we will do anything for those that we love.

I find subversive humor in these images. For example, the pedicure obscured by a candlestick. A pot plant that covers a body. Three subjects eating bananas! Here, visual pleasure is rooted in discomfort and disruption. These are objects that seem both accidentally and intentionally symbolic-without commodifying desire. Is this a conscious objective for you, to subvert signification?

JEANETTE SPICER: I definitely try to subvert humor, and I am so glad that you experience this in the work! Many people don’t realize that I actually consider some of my work to be funny, because it is more formal, or serious if you will, but, yes, I think a lot about humor, more in line with my own, which is sarcastic, very tongue in cheek. I like to obscure parts of an image, and there are different reasons for why I do it. Sometimes it is for humor, sometimes it is so the viewer can concentrate on specific parts of the body. In terms of symbolism, I definitely think about that in terms of the banana, which is a good example. It is phallic and silly, but also something we all eat, right? I always make an effort to imply, suggest, subvert and do so in a subtle way. I want the audience to ask themselves questions, I don’t want to ask them loudly, and I certainly cannot answer them.

Wikipedia has invited you to write an entry on the Lesbian Gaze. How do you define it? What do you include?

JEANETTE SPICER: This is hilarious! Very much unique to each lesbian, but, for me, it is about unlearning male desire when it comes to how women are portrayed in art. It is also about creating new worlds and possibilities for all that I am, all that I see and those whom I love and respect.

Get Jeanette Spicer’s To the Ends of the Earth here.

Save the date for the next Curve Photo Contest. Submissions open March 2025.