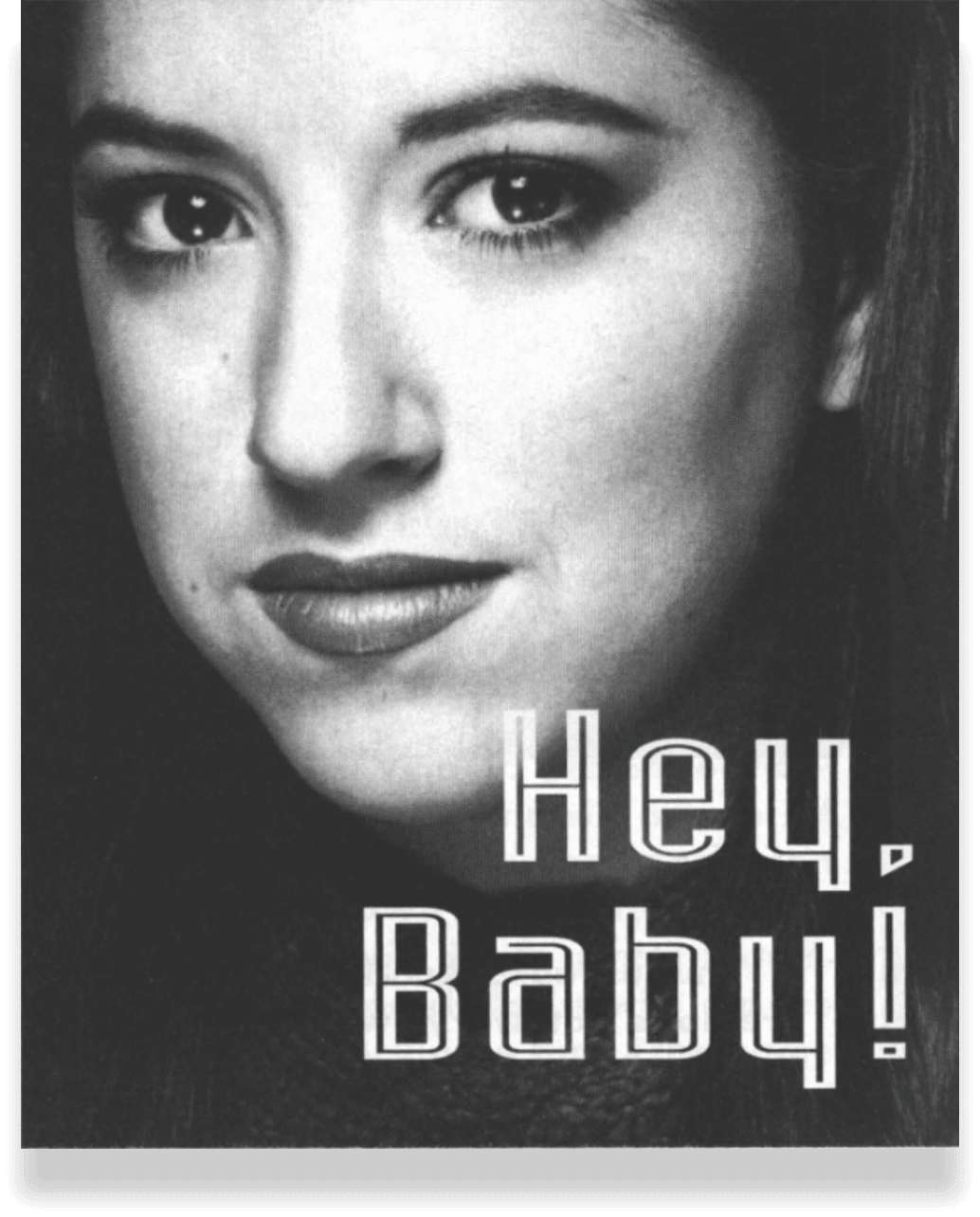

With America’s best-known newsstand magazine for lesbians being started by 23-year-old Frances Stevens, it made sense that the publication, among its regular departments, would have a column focused on lesbian youth. Reflecting back on the Hey Baby! column, which ran from 1993 to 2004, Stevens says, “One of the big points behind creating the column was that, before social media, the place where most lesbians and queer people met up was at the bars. If you were under 21, that left you alone on an island.”

While lesbians in their prime flocked to gay and lesbian bars, nightclubs, and of course The Dinah, younger lesbians didn’t have many ways to find each other or to discuss the issues that concerned them. And some of these issues were serious and urgent, such as coming out safely, gender identity, mental health, and how to navigate those first intense same-sex relationships.

Studies have shown (and still do) that young LGBTQ+ folks suffer more bullying, harassment and mental health challenges than their heterosexual counterparts. In the 90s, when lesbian chic was starting to trend, who was listening to baby dykes?

“Baby dykes,” as young lesbians were called back then as a term of endearment, were a visible if silent part of our community, so shouldn’t a lesbian magazine also speak to them?

The Hey Baby! column was introduced in Curve magazine, formerly known as Deneuve, in 1993. It was a regular feature in most issues until 2004 when the columnists themselves aged out. The magazine then continued to address younger dykes as part of its general content. But the column, much like beloved regular columns “Fairy Butch” and “Lipstick & Dipstick,” homed in on the voices and needs of a niche lesbian demographic.

The column aimed to provide a safe space for young readers to express themselves and be heard. It encouraged self-reflection and acceptance. During its run, “Hey Baby!” had three writers, each with their unique perspective and writing style. They all shared a youthful energy and crafted content that catered to lesbian and queer minors and those starting their journey into the lesbian community.

The first writer, Bree Coven, 20 at the time, launched Hey Baby! by offering gay youth relationship advice and methods of finding communities of other gay kids. Expanding on these same themes, later authors Jen Louise Dunning and Gina Stella dell’Assunta transitioned to featuring and sharing Curve’s platform with inspirational queer youth.

“We wanted to highlight young females who were courageous to be out and expressing themselves creatively through activism, art, music, literature and politics,” Dunning said. “This was before the web, and this sweet and brave magazine gave queer women visibility and brought interesting, relevant articles to women all over the country.”

In the first Hey Baby! article from 1993, Coven rolls out the rainbow carpet. “Welcome to the new baby dyke column for, by, and about lesbians under 21. My name is Bree and I’ll be your hostess.” Coven then shares her coming out at 18 and her visit to a dyke bar as a “rite of passage.” She tries to enter using a borrowed ID and is stopped by “a big butch bouncer” who spots the ruse immediately. She is shown the door but Coven implores her: “Look, don’t you remember when you were 18 and you felt so alone and all you wanted was to go somewhere and meet other people like you? Maybe she did remember, just a little bit, because her face softened and she grumbled,’Oh, just go on in and get outta my sight.’ ”

Coven continues: “And so a baby dyke was born. But sometimes we can’t get in. And sometimes we don’t even want to. And sometimes we’d rather hang out with dykes our own age. I think we’re all aware that, as women and as lesbians, we face an unfortunate amount of prejudice in society. Add that to the fact that young people all over the world are considered second-class citizens, and we become triple minorities, the least visible of the gay community. This can be further compounded for those of us who are ethnic or religious minorities. That’s why I think it’s so important for us to find and use the resources available to us.”

Coven recalls of that time, “Connecting with my community was really rough.” Prior to the Internet or social media, magazines were our most powerful tool.

But while the Internet has helped many find communities of fellow queer youth, some teens report being unable to determine if an online source with information on LGBTQ+ identities is trustworthy.

“If you have someone to talk to that’s not on the Internet, you’re able to get a much more human response, or a more realistic and less radicalized, reliable one,” Sequoia High School Gender Sexuality Alliance (GSA) Co-President Ethan Thacker said. “I would have loved someone to actually talk to when I was younger instead of a BuzzFeed Quiz.”

Social media has many other downsides as well.

“There’s a lot of cyberbullying and a lot of misinformation perpetuated in this whole radical, right-wing idea of people hating and gathering online,” Sequoia GSA Co-President Zoraya King adds.

Today’s teens having more identities and labels to describe their sexuality, romantic attraction, and gender has also come with unexpected consequences.

In a 1993 Hey Baby! article titled “The Butch/Femme Dilemma”, Coven writes about the pressure on lesbians to choose between the dominant, masculine label “butch” or the submissive, feminine label “femme,” which were the only labels lesbians had access to at the time.

She later notes this affected her experience of coming out where she was met with resistance from her peers that she feels might have been lessened had the community had more labels to choose from.

“I came out as a femme, and all I knew was that everybody told me you don’t look like a lesbian, so you’re not,” Coven explains. “I came out into a vacuum with no words, and I thought there was something wrong with me.”

While LGBTQ+ kids now have more language to use when they come out, it may feel overwhelming and add to an already stressful time.

“It’s this pressure from society and peers around you that you need to come out as something even though you haven’t really discovered yourself, and, in turn, it can lead to discomfort,” Abel Chavez, secretary of Sequoia’s GSA, observes.

Even with the many differences that separate the experiences of being young and queer today and in the ’90s-2000s, there are universal struggles that LGBTQ+ youth of any era have, which can be alleviated with support from older generations.

One of these is navigating the challenges of a first same-sex relationship.

In a 1994 Hey Baby! article titled “The Joys & Perils of Older Women,” Coven wrote about the common occurrence of young lesbians who have early relationships with older lesbians. She received many responses from women with similar experiences.

“I remember hearing from a young woman who didn’t know anyone else in that predicament [dating older women], and she felt like she couldn’t talk about it without being judged by regular straight society and by her own queer friends,” Coven recalls.

Although not with an older person, King also describes asking an older lesbian family friend for guidance on her first gay relationship.

“Having somebody to vent to that went through very similar experiences and getting to know [a trusted gay adult’s] story too helped me a lot,” King adds. “Especially when I was going through my first relationship and figuring out how women work and how they don’t work.”

Another hot topic: Coming out at home. Coven shared how her family disowned her after coming out as a teenager and found the experience understandably scary. “I didn’t have my family anymore, and I was on my own in New York City at seventeen,” Coven said.

Chavez has also experienced family members being unaccepting of their LGBTQ+ identities.

“My mom is supportive of my queer identity, but she does tell me to hide myself in front of my dad because he himself isn’t supportive,” Chavez adds. “It just taught me to hide.”

For many LGBTQ+ teens, facing homophobia or isolation at home or school is eased by seeking support from a trusted gay adult.

For those who grew up in the ’90s, Hey Baby! would have been a great source of support, and Coven offered it even in the inaugural column, highlighting vital organizations such as the Hetrick-Martin Institute in New York City, which offered services and shelter for LGBTQ+ youth.

Because she didn’t have Curve when she came out, after coming out and losing contact with her family, Coven received support from older gay people in her community. Her acting coach loaned her money for her first apartment, and a lesbian who knew Coven through theater invited her into a family of older lesbians.

“They all kind of mothered me — they taught me how to make an omelet, invited me to Christmas, and encouraged me to go back to school,” Coven adds. “It was vital for me.”

In a 1995 Hey Baby! Article, a 17-year-old lesbian, Molly Hendricks, was spotlighted and discussed how having an accepting teacher at her high school allowed her to come out.

“I found out my teacher was gay and I talked to her about it, and she helped by setting up a class to make it easier for me to come out there,” Hendricks said.

GSAs help bridge this gap. Members of Sequoia High School’s GSA are grateful for the many out LGBTQ+ teachers and staff members.

“Adults [in the Sequoia community] being able to express themselves freely now allows students like me who are trying to come to terms with their identity to find someone who they can look up to and someone who can help them throughout their journey,” Chavez adds.

Unlike gay teens who had Curve and Hey Baby!, and modern teens who attend LGBTQ+-friendly high schools, some LGBTQ+ youth have no access to any kind of accepting community.

“A lot of [LGBTQ+ teens] don’t have even one person that they can turn to, maybe not even a friend or a classmate,” King notes.

Dunning’s experience growing up was similar, as her suburb in Sacramento had no LGBTQ+ visibility. She describes how this affected her and others in similar situations.

“Anyone who starts to question their sexuality currently and identifies as something other than straight in a heteronormative society may struggle and may suffer from homophobia and/or transphobia and have feelings of being alone,” Dunning said.

Curve served LGBTQ+ teens who experienced this in the ’90s and 2000s and continues the work today for modern teens. The Curve Foundation has younger as well as older LGBTQ+ staff who provide resources for LGBTQ+ people of all ages. Continuing the practice of Hey Baby! articles, The Curve Foundation offers The Curve Award for Emerging Journalists for new LGBTQ+ journalists and created the Beyond the Rainbow project, which also encourages intergenerational conversations between LGBTQ+ people. Queer teens can also check out the Curve Archive where they can read all past issues of Curve/Deneuve, including Hey Baby!

Because of the ways the LGBTQ+ community has evolved, some of the advice or language in Hey Baby! articles doesn’t apply to current LGBTQ+ teens. Gender identity has overshadowed sexual expression and the issue of trans and non-binary identities as well as androgynous language has replaced the discussion of ‘roles’ such as “butch” and “femme,” labels that Coven wrote about in 1993. The word “dyke” or “baby dyke” as a label for a gay woman or young gay women is also not as popular today, although it is being reclaimed by some queer women.

However, much of the content rings true today and can help teens feel connected to their LGBTQ+ history. Spotlights about the social justice movements young gay people of the ‘90s were involved have a through-line to current work by and for LGBTQ+ youth. In a 2002 Hey Baby! article by Gina Stella dell’Assunta, 17-year-old Beatrice Sullivan speaks about her involvement in the Know Your Rights Project and her intersectional activism for Black lesbians. More than 21 years later, The Curve Foundation aims to carry on this work, especially with emerging journalists who are the voices of their generation.

Visit the Curve Archive and search for Hey Baby!