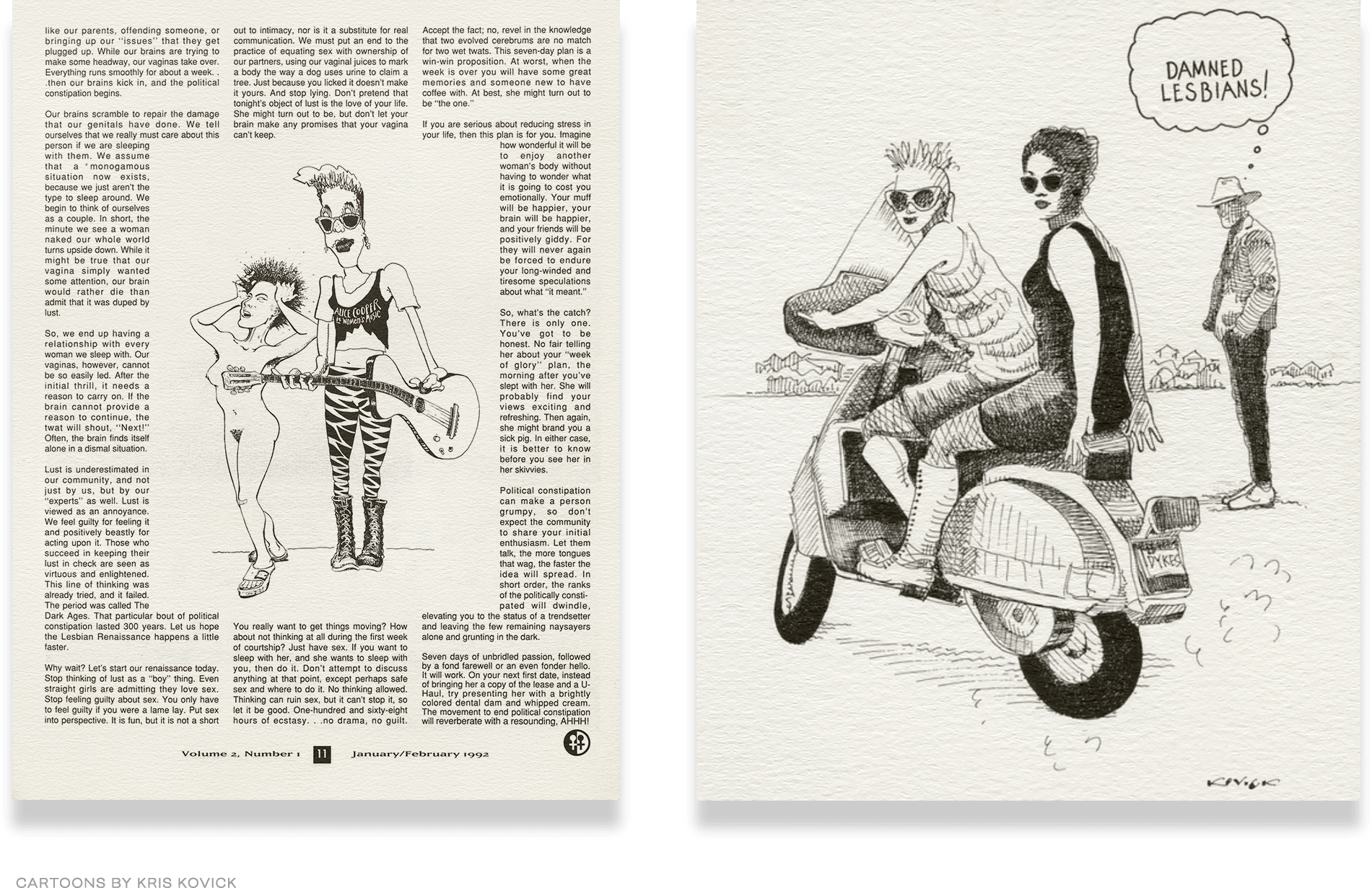

On Thursday, July 13, The Curve Foundation opened the exhibition, Curve Magazine Cartoons: A Dyke Strippers’ Retrospective at the GLBT Historical Society Museum in San Francisco. Curated by Julia Rosenzweig, the Archive and Outreach Manager at The Curve Foundation, the collection of works features cartoons published in 1991-1999 issues of Curve and Deneueve.

Hilarious and creative, publishing these images on a platform like Curve magazine allowed queer women to represent themselves and their culture through art. As there were few places lesbian artists could display works so unapologetically gay, A Dyke Strippers’ Retrospective celebrates Curve’s pioneering work to give lesbians another medium to see themselves in.

“The only places that would publish cartoons with ‘subversive’ topics in the 1990s were underground zines and alternative or indie publications,” Rosenzweig said. “It’s so important that the story of Curve magazine — a mainstream lesbian publication publishing this art — should be told.”

“It’s so important that the story of Curve magazine — a mainstream lesbian publication publishing this art — should be told.”

Julia Rosenzweig

Comic strips have been popular in the US for almost a century giving us Superman, Archie Comics, Garfield and many more. LGBTQ+ comics didn’t have the same notoriety due to general homophobia and self-censorship.

Riding on the wings of McCarthyism, a moral panic about the media’s effect on children claimed comics encouraged criminality. In 1954, The Comics Magazine Association of America was created and in response to the allegations, created the Comics Code Authority (CCA). If a comic had the CCA stamp of approval, it complied with a set of rules preventing criticism of law enforcement, crime and sexuality being represented. While LGBTQ+ characters weren’t directly prohibited, it was implied, and many publications were not willing to risk it.

Starting in the 1960s, many comics were published outside the mainstream in the underground Comix movement. As these were countercultural, LGBTQ+ artists began presenting their work.

In 1972, Trina Robbins illustrated “Sandy Comes Out,” which was featured in the all-women’s collection of comics, Wimmen’s Comix. While created by a straight woman and not considered to be the best lesbian representation, it is considered to be the first lesbian story told through comics.

Mary Wings created the first gay comic book, Come Out Comix, a year later about her journey coming out as a lesbian. As attitudes shifted and more alternative publications arose in the 1980s, gay artists had more opportunities to publish their work.

In 1983, Rupert Kinnard was able to publish in “Just Out” where he presented the first Black gay comic characters, The Brown Bomber and Diva Touché Flambé.

Beginning writing and illustrating in 1983, Alison Bechdel published her series “Dykes to Watch Out For” in many alternative publications during its run from 1983-2008. She would also create a graphic novel about her childhood and coming out story, Fun Home, in 2006, which would be adapted into a Broadway musical in 2013.

Displayed at A Dyke Stripper’s Retrospective, a 1993 issue of Curve (then titled Deneuve) included a feature on Bechdel where she touched on her passion for representing complex, gay women in comics.

“I want to draw real women with real bodies and feelings and ideas, women who are adorable, irritating and independent, committed and frazzled,” Bechdel said. “Mostly I want to draw women who are lovable and who love other women.”

According to Rosenzweig, Bechdel was not alone in her desire to see more realistic LGBTQ+ people.

“I think these cartoons were integral to lesbians seeing themselves reflected in popular culture, even if it was a fairly niche part of it,” Rosenzweig said. “I can speak to its impact on the community only through anecdotes that I heard from the cartoonists themselves, which is gratitude from readers for having created comics that displayed queer life at the time.”

A Dyke Strippers’ Retrospective highlighted work that not only included gay women but accurately represented gay sex and advocated for safe sex practices such as using latex barriers for oral sex.

Curve ensured these topics were illustrated in the ’90s as, in the previous decade, the AIDS crisis prompted more sex education to be offered.

The Retrospective not only focuses on work with an LGBTQ+ angle but showcases artists who spoke out about other social issues.

Cartoonist Jennifer Camper, a Lebanese-American, has three pieces in this collection critiquing traditional family values, sexism in medicine, and racism in America.

The exhibition also honors the aesthetic value the comics provided. A placard below a section with examples of Curve magazine pages that featured cartoons titled “How They Filled The Page” adds that the art served as page headers and accompanied advertisements as well.

Overall, Curve Magazine Cartoons: A Dyke Strippers’ Retrospective is able to examine both the historical significance of Curve magazine printing cartoons and the relevant messages LGBTQ+ artists included.

Along with “great” ticket sales, Rosenzweig adds that the event is succeeding in accomplishing its other goals.

“We created space for the community, got to share parts of Curve magazine’s history, showcased some amazing cartoons and artists, and displayed to folks what The Curve Foundation can achieve,” Rosenzweig said.

In 1994, Bechdel asked some interesting questions: “What happens when it’s more acceptable to be a lesbian in our culture, which it’s becoming more and more,” Bechdel said. “What happens to my strip? Will there still be a need for it?”

Present-day can provide answers. There appears to still be not only a “need,” but a desire for more LGBTQ+ art. The Curve Archive includes all other art published in Curve magazine that wasn’t displayed at the exhibition. In general, LGBTQ+ art and cartoons are still thriving today in part because of the contributions of artists and publications like Curve.

Cartoons: A Dyke Strippers’ Retrospective is now showing until the Fall at the GLBT Historical Society Museum in San Francisco.

Check out the Curve Archive and the The Curve Foundation website to browse all 30 years of Curve magazine and see what else we’re up to! And if you really want to nerd out on queer comics, check out the Queer Cartoonists Database and find your next favorite artist.