When bell hooks (born Gloria Jean Watkins) died on December 15, 2021, she was only 69. There were many more years we–feminist, gay, lesbian, queer people–needed from her.

When asked about her sexual identity, hooks described herself as “queer-pas-gay,” exemplifying her insistence that no one define her but her. hooks asserted, “I will not have my life narrowed down. I will not bow down to somebody else’s whim or to someone else’s ignorance.”

Throughout Black History Month and Women’s History Month, mainstream and independent sites tend to focus on the same figures, time and time again. But, the voices of Black lesbians and queer women are too often missing from these commentaries and highlights.

Even at bell hooks’ death, her sexual identity was obscured, despite having written more provocatively about love, commitment and the philosophy of caring than nearly any writer in recent decades.

She was prolific, making up for lost time—not just for herself, but for Black women throughout history. In Remembered Rapture: The Writer at Work, hooks said, “No black woman writer in this culture can write ‘too much.’ Indeed, no woman writer can write ‘too much’ … No woman has ever written enough.”

As a member of our community, bell hooks is one of many Black and queer women, past and present, who have fought for their agency.

Here are some more:

Angelina Weld Grimké (February 27, 1880-June 10, 1958), of the abolitionist Grimké family, was the granddaughter of a white slave owner and a Black enslaved woman. Grimké wrote essays, short stories and poems often published in “The Crisis,” the NAACP’s newspaper, which was edited by W. E. B. Du Bois. A member of the Harlem Renaissance, Grimké was also the first woman of color to have a play, entitled Rachel, produced in the U.S.

At the age of 16, she wrote to a friend, Mary P. Burrill, 15: “I know you are too young now to become my wife, but I hope, darling, that in a few years you will come to me and be my love, my wife! How my brain whirls, how my pulse leaps with joy and madness when I think of these two words, ‘my wife’.”

Mary P. Burill (August 1881–March 13, 1946) would herself become a well-known Black playwright and writer , and educator who became the first Dean of Women at Howard University. Her best-known plays are The Other Wise Man (1905), They That Sit in Darkness (1919), and Aftermath (1919). She was an outspoken about the horrors of lynching and advocated for birth control, publishing plays in radical journals of the time including Margaret Sanger’s Birth Control Review and the socialist journal The Liberator. After her relationship with Grimké, she lived with Lucy Diggs Slowe (July 4, 1885-October 21, 1937) for 25 years and their home, The Slowe-Burrill House, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2020.

Mabel Hampton (May 2, 1902-October 26, 1989) was an early lesbian activist, a dancer during the Harlem Renaissance and a volunteer for both Black and lesbian/gay organizations. Throughout her adult life, Hampton cleaned houses for white families in New York City, which is how she met Joan Nestle (born May 12, 1940), co-founder of the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA).

Hampton’s careful and extensive collection of memorabilia, letters and other records are considered crucial ephemera documenting the lives of Black lesbians during the Harlem Renaissance. Hampton donated that collection to the LHA, along with her considerable lesbian pulp fiction collection.

Hampton lived with her partner Lillian Foster for over 40 years, until Foster’s death in 1978. Hampton spoke at the New York City Pride march in 1984, saying, “I, Mabel Hampton, have been a lesbian all my life, for eighty-two years, and I am proud of myself and my people. I would like all my people to be free in this country and all over the world, my gay people and my Black people.”

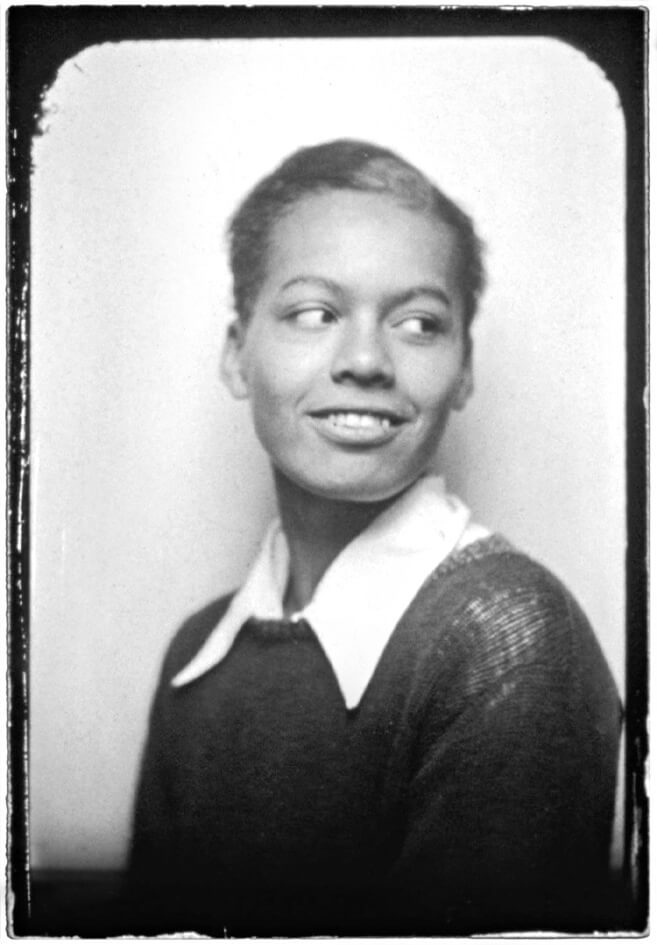

Pauli Murray (November 20, 1910-July 1, 1985) An iconoclastic socialist-leaning, gender-fluid feminist and Black Civil Rights activist, Murray broke barriers in every aspect of her life — a life of firsts: First Black woman law school graduate at Howard University, first Black person to earn a JSD (Doctor of the Science of Law) degree from Yale Law School, first Black woman ordained as an Episcopal priest.

Her legal writings were the predicate for Thurgood Marshall’s segregation-shattering 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case, Brown v. Topeka Board of Education. And her name was also listed as co-author on the brief argued by Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1971 in Reed v. Reed. Years later Ginsburg referred to Murray when she said, “We knew when we wrote that brief that we were standing on her shoulders.”

At various times, Murray identified as a man and dressed in androgynous clothing. As the Pauli Murray Center details, “Murray actively used the phrase ‘he/she personality,’ during the early years of her life. Later in journals, essays, letters and autobiographical works, Pauli employed ‘she/her/hers’ pronouns.”

Murray believed that “true community is based upon equality, mutuality, and reciprocity. It affirms the richness of individual diversity as well as the common human ties that bind us together.”

Audre Lorde (February 18, 1934-November 17, 1992). The writer, civil rights activist, lesbian activist and scholar described herself as “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” Lorde is perhaps the best-known and most-quoted Black lesbian writer. Her work–notably Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches–is considered one of the singular classics of lesbian literature and 20th century Black writing.

One of Lorde’s most famous quotes is, “Your silence will not protect you,” from her essay, “The Transformation of Silence into Language and Action.” In that essay Lorde explicates how Black women are manipulated into silence– and thus complicity–by a gaslighting culture that terrorizes them and leads them to believe that silence will keep them safe from attack from white, male patriarchal society.

Lorde’s extensive and explosive work–nine volumes of poetry, five works of prose and countless lectures, speeches and interviews–is also among the first to address disability and chronic illness as she wrote about her experience with metastatic breast cancer, which ultimately lead to her untimely death at the age of 58.

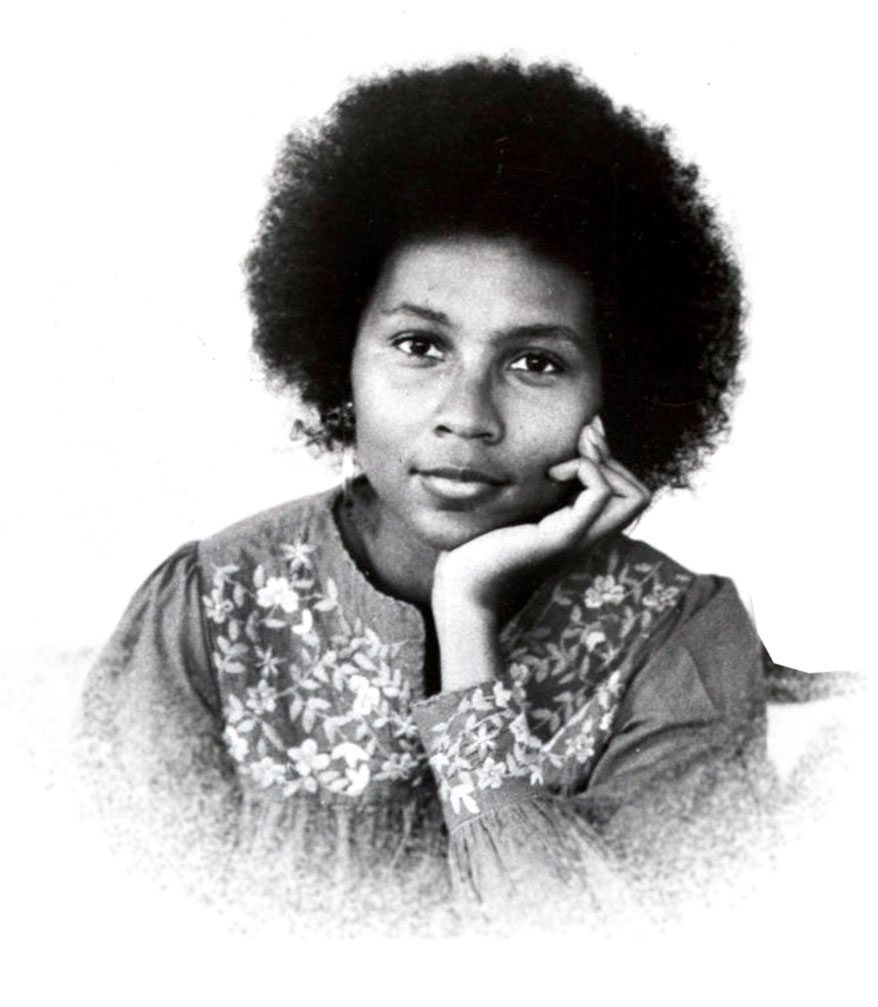

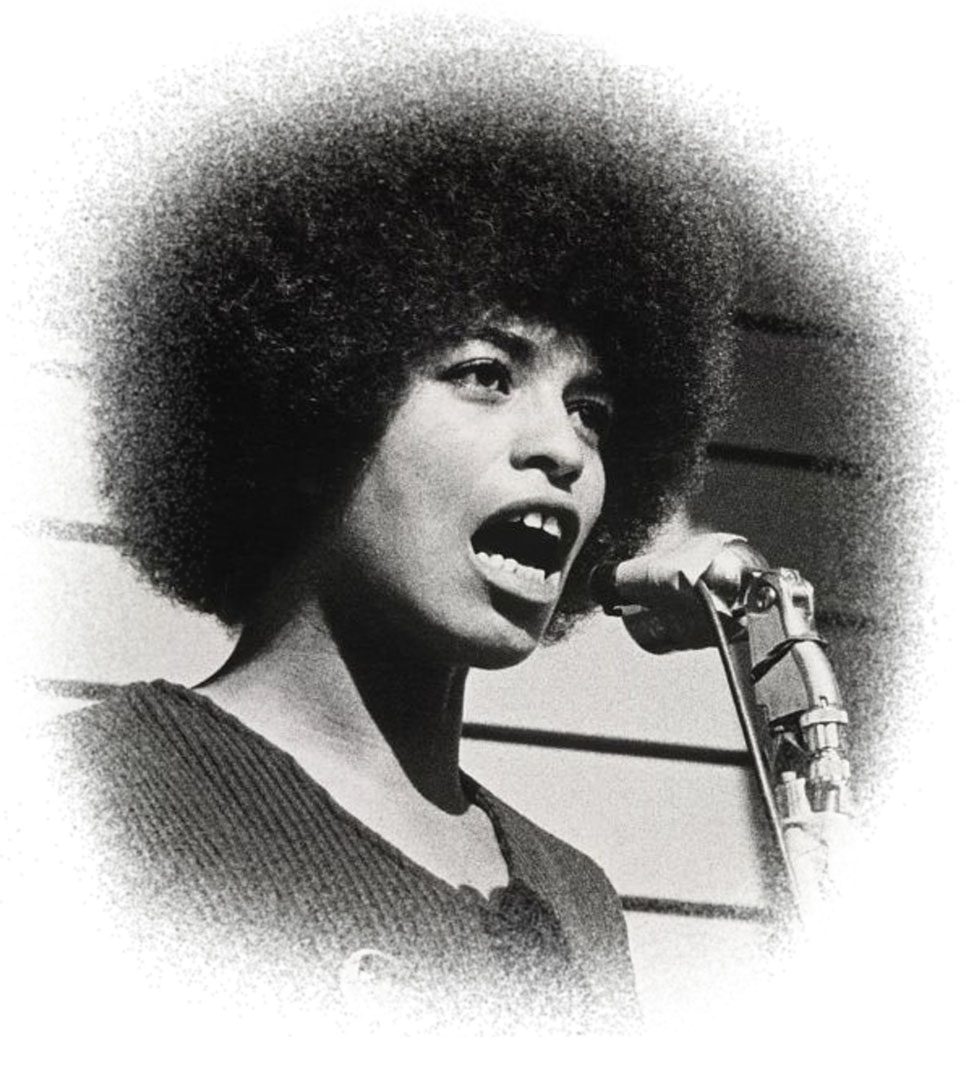

Angela Davis (born January 26, 1944) is a political activist, philosopher, academic, scholar, writer and the author of over ten books on class, feminism, race, and the U.S. prison system, of which she is one of the staunchest critics.

A radical political activist and theorist, a member of the Communist Party and the Black Panthers, Davis gained fame in the 1960s and 1970s as a leader in the Black Civil Rights, Black Power and Black and feminist liberation movements. Pivoting off the Serenity prayer, Davis’s most famous quote is the one that threads through all her activism: “I am no longer accepting the things I cannot change. I am changing the things I cannot accept.”

She wrote, “You have to act as if it were possible to radically transform the world. And you have to do it all the time.”

Davis came out formally as a lesbian in 1997 in an interview with Out magazine. Her life partner is fellow professor and scholar Gina Dent, with whom she has collaborated on several projects, most recently Abolition. Feminism. Now., published in January, 2022.

In many ways, Imani Rupert-Gordon (born April 16, 1979) continues the work of women such as Angela Davis. As the executive director of the National Center for Lesbian Rights (NCLR), a national legal organization committed to advancing the civil and human rights of LGBTQ people through litigation, legislation, policy and public education, Rupert-Gordon believes we must expand our political perspective and radical purpose as activists, and as a community.

“Racial justice is an LGBTQ issue, and so too are issues like police violence and accountability, creating true safe communities, over-incarceration, issues of poverty, decriminalizing sex work, fundamentally changing the child welfare system,” she said.

“As the first Black woman to lead NCLR, I want everyone in our community to feel recognized, especially those who aren’t used to seeing national organizations represent and champion their issues,” she said.

There are countless Black queer women who need to be supported and celebrated as they do the vital work to “radically transform the world,” to quote Lorde, refusing to have their lives narrowed down, in the spirit of bell hooks — but rather, as Pauli Murray envisioned, affirming diversity as well as the ties that bind us together. Curve honors them and carries their work forward.