Jasmine Sudarkasa is six feet tall with a star that’s been rising for some time.

She tells us she comes from “many generations of very tall, very strong, very dark-skinned Black women, and there’s a lot of power in that identity, but there’s also a lot of danger in that identity in these United States.”

Because Sudarkasa understands that danger, as part of her work with Girls Educational & Mentoring Services (GEMS) she trained more than 1,000 law enforcement officers, legal folk, and child welfare providers on best practices in serving commercially sexually exploited youth.

She then moved into philanthropy. As a program Fellow at the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, she contributed to effective philanthropy, consulting on grantmaking strategy and evaluation, organizational effectiveness and equitable practice. In 2020, she designed and led a $15 million anti-racist grantmaking effort, a personal and career highlight.

Jasmine also happens to be a queer cisgender woman who uses she/her pronouns.

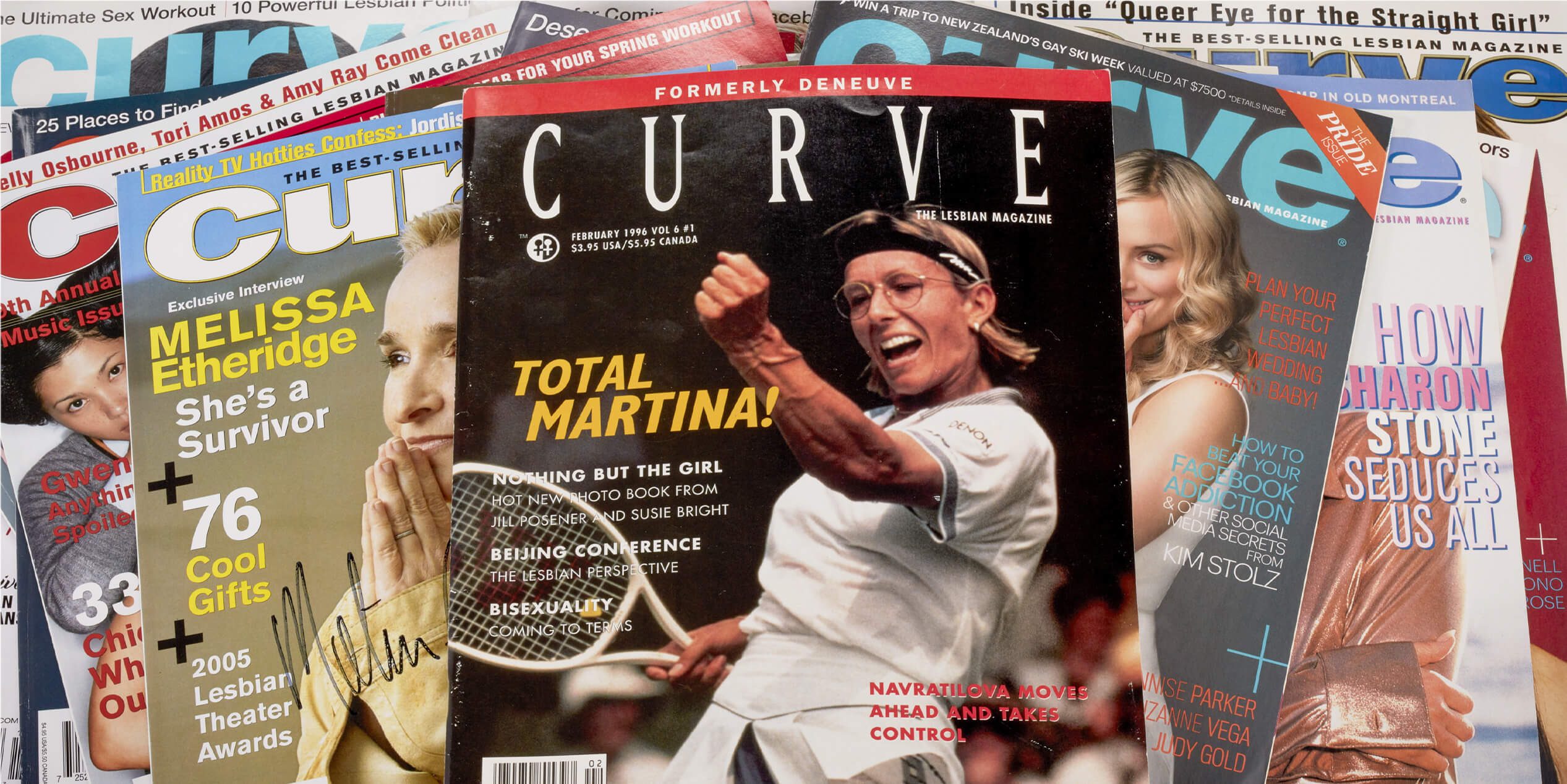

These biographical and professional details are important for the work that Sudarkasa is about to embark upon as the incoming Executive Director of The Curve Foundation: honoring, uplifting, and expanding 30 years of Curve magazine’s community legacy.

It seems fitting that Sudarkasa is the same age as Curve, because while her life in years spans its existence, she came to the publication “fairly late.”

“It was kind of like coming home to myself. When I was watching the documentary Ahead of the Curve, and looking at the Curve magazine archive, the subtle lines of communication and impromptu spaces that I’ve held with many people felt like they were present in that film and on those pages. Those secret conversations or the spaces that I didn’t believe exist in any kind of memorialized way — they live in this magazine. So accepting the position felt full circle for me.”

When Franco Stevens started the magazine 30 years ago, she was willing into existence a space and a service for an under-served and largely invisible demographic: lesbians and queer women. That effort has not been lost on Sudarkasa. In fact, it has run parallel to, and helped to confirm her identity.

“I spent a long time trying to figure out what I was. For many of us,there is that experience of knowing you fit somewhere, but it’s not here. And lesbians identified me. They saw me. They would connect with me. They would ask me questions about myself that I was not asking. It was such an unlocking of self. I think a lot of folks want that experience of being seen whether or not you are yourself a lesbian, but being truly seen, by your first partner or by whoever. It’s really powerful. And I think the magazine in its own way replicates that experience. You see yourself not just in the present, but in history. That’s so important. It was for me and I think it will be for those who we can expose to the magazine and the Foundation.”

Sudarkasa was partly inspired to apply for the job with the Curve Foundation because of the scene in Ahead of the Curve in which Franco asks a crowd at a large LGBTQ+ conference if the word lesbian matters anymore. The scene goes on to confirm that it does. Lesbian culture resonates with Sudarkasa and even though her lived experience is queer — and our community has evolved to include a plethora of self-identifying terms — in her view, this does not “disempower the political and historical salience of the term lesbian,” she says.

“And I don’t think it’s appropriate to erase women who are lesbians. Now that we have dozens of terms to effectively communicate gender identity and sexual identity, what I think these terms are about is affinity. So, if I see the word lesbian and I have an affinity with or respect for it, I may be drawn to that space even if I am not a lesbian. And I think the responsibility is on those of us who hold the space to make it a place where people can belong. I believe in the importance of the lesbian political, social, and romantic identity. It’s important to me to embody fluidity while holding deep respect for the historical significance of the term lesbian and using it as an invitation to those who may see themselves in what we’re trying to accomplish.”

And what she hopes to accomplish is a lot: to help turn a magazine that has touched and nurtured the lives of hundreds of thousands of queer women and lesbians over the last 30 years into a philanthropic endeavor that will do the same and more for another 30 years at least.

Those three decades of history are rich with “an incredible cross-generational dialog” that is in some ways unique to “those of us who have to seek spaces outside of our first families to find ourselves.”

“And so, my vision for the Foundation is that it can be that institutional home that reflects the community without perpetuating the injustices of traditional institutions. I want to create a home for some of this joy. I think what Curve will add to the cultural zeitgeist is a place to play and to share space, to bolster culture and build community, and most importantly, to do that across generations.”

The LGBTQ+ community has dramatically evolved in just a handful of years, particularly around gender identity and expression, about intersectionality, and systemic injustices around race, class and gender.

“There are conversations that we haven’t had the time to have as a community. I think this is the time,” says Sudarkasa.

If not for this, Frances Stevens and Jasmine Sudarkasa might not have met. And even if they did, let’s say in some iconic lesbian bar like Sue Ellen’s in Dallas or the Cubbyhole in New York, would they have crossed the space to speak to each other? Would it have been evident that they had anything in common? Those spaces, which are already coded along cultural, racial, class and generational lines have a limited function.

“This is exactly why the Foundation needs to exist,” says Sudarkasa. “I really see our role as connecting the dots. It’s going to take some legwork and I’m ready to do it.”