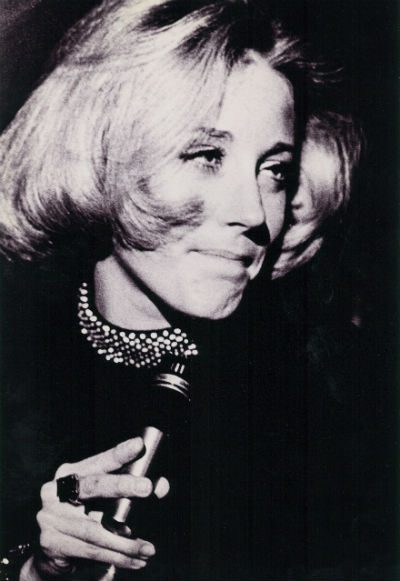

A personal tribute to the late pop star

One night in 1970, after dancing at one of the many gay bars in New York City at that time, two gorgeous young women are making their way home through Central Park, where they stop to have their first kiss.

They’re hot for each other, maybe even in love, but there are no thoughts that night of a future. They couldn’t know then that time would separate them and bring them back together to share their lives for 32 years. There are no thoughts that night of the dangers that lesbians often meet walking along the street together. There are no thoughts that night at all. Just two people in the throes of passion, made dizzy by that kiss, having a moment of reckless pleasure. A moment interrupted by sirens and the police who are about to haul them off to jail for the crime of being two women kissing. Until one of the officers recognizes one of the women. “You’re Lesley Gore! I love your music.” And he lets them go.

Not so accommodating is the owner of a club where Lesley has been booked to sing. After she finishes her set, he shows up with Dobermans and refuses to pay her because she is a lesbian. He threatens to sic the dogs on her if she ever comes back to town, calling her a “a big dyke!”

But, those incidents and injustices, which she would later fight against and march alongside others to change, had not yet happened to 16-year-old Lesley Gore, who was driving home from school one day in 1963 on the suburban streets of Teaneck, New Jersey. With the radio blasting. And the top down on her bottle green Jag XKE convertible. She’d already met Quincy Jones, the man who would change her life, as she would change his. And she’d just finished recording a demo for him called “It’s My Party.” What she didn’t know as she sang along to the radio, and whatever was popular that week, was something Quincy himself had just learned a few nights before—that another producer had just gotten “this great new song—It’s My Party” and was going to give it to his own well-known group, the Crystals. Without saying a word, Quincy went back to the studio, stayed up all night pressing copies of Lesley’s recording, and rushed them to 100 radio stations. When Lesley Gore, alone in her car and unaware of what was going on behind the scenes, suddenly heard her own voice boom out over the speakers, she started beeping her horn, stopping pedestrians and drivers in their tracks, yelling out, as if she herself couldn’t believe it, “That’s me. That’s me. I’m on the radio!”

I met Lesley Gore and Lois Sasson 20 years ago in New York City at a Town Hall Event for Women produced by Lois, Patty Goldstein, and the staff of W.E.D.O. I briefly shared the stage with luminaries like Bella Abzug, Lauren Bacall, and Betty Comden, reading an excerpt from my new play, My Left Breast. Having just emerged from my writer’s cave, and overwhelmed by the positive response, I went off to hide. They searched for me afterward. I was found. Embraced. And in an instant I was theirs.

They introduced me to Nela Wagman, the woman who would ultimately direct the play. They took me to dinner with the Broadway producer, Marty Richards, whom they hoped would produce it. Instead, he asked me to write his memoir. Said he’d set me up at his beach house. (I declined, fool that I am.) They wanted the best for me. Invited me to their place in the Hamptons. I got to see Lesley perform at Joe’s Pub. She donated generously to my web series about young lesbians. She asked me to collaborate on writing the book of a musical about her life. She sent me all her recordings. I listened to every cut as her journals and notes started arriving by messenger. We never made it happen, she and I.

Today, I’m standing at the door to Lois and Lesley’s apartment. Hesitating. I don’t want to cause Lois more pain by asking her to talk about Lesley when she’s just lost the love of her life. A dog barks. It’s Billie (named for Billie Holiday, of course), who’s blind and deaf and has also lost the love of her life. Lois hugs me. “Hi, baby. Come in.” And she opens the door to me and my questions. With the gift of her story. Their story.

In 1970, Lois Sasson and Lesley Gore, just kids, have an illicit affair. They break up. Lesley moves to California, and Lois continues her political work in New York, producing feminist theatre, like The Three Marias at Circle in the Square and later at the Public Theatre. Years pass. Then, in 1982, Lois gets a call: We need a singer for the SAGE Benefit. She doesn’t hesitate. “How about Lesley Gore?” After all this time, Lois calls Lesley. “You have to do me a favor and I’ll forgive you everything. Come do this. It’s time to be political.” And over an advocacy action, they were back together. “That was it,” Lois says. “Together till the end.”

“I’m Lesley Gore and I approve this message.” —You Don’t Own Me P.S.A.

Lois tells me Lesley always felt guilty that as a teenager, because of pressure from her parents and her record label, she couldn’t be more visible in her political stances. But in her 20s she worked for Robert Kennedy. Rallied against Nixon. And one night, appearing on the Mike Douglas Show, after killing the crowd with her jazz rendition of “Sit Down, You’re Rockin’ the Boat,” she joined the host and his other guests, among them Barry Goldwater, a political conservative who was a staunch supporter of the Vietnam War, and without raising her voice or damaging her formidable vocal cords, she roundly put him in his place. “Lesley was smart as a whip,” says Lois. In 2001, Lesley joined other artists to perform at a conference sponsored by The N.Y. Coalition of Professional Women confronting the prejudices faced by women over 40 in the performing arts. And in 2011, she went on to make a public service video that went viral in support of women’s rights and getting out the vote, in which she’s joined by a chorus of women and girls of all ages (including Lena Dunham) lip-synching to her powerful rendition of “You Don’t Own Me.” When it comes to the lyric “Don’t say I can’t go with other boys,” one of the women holds up a handwritten sign that says “girls.” At the end of the song, Lesley appears on the roof of her building, addressing the camera. “I recorded ‘You Don’t Own Me’ in 1964. It’s hard for me to believe, but we’re still fighting for the same things we were then. Yes, ladies, we’ve got to come together and get out there and vote and protect our bodies. They’re ours.”

“We were always out as a couple.” —Lois Sasson

Was there a difference in how each of them felt about being out in the world? “Lesley was a very private person. She didn’t care that anyone knew she was gay. She was always out, even though whatever she did she might have done quietly. For her, it was a different experience. She felt her sexuality hurt her in show business. Her sexuality was brought up as a turn-on, a conquest. We were always out as a couple, but those early years were hard for her. So we had an underground life—the bars. I took her to all of them. The lesbians were usually hidden downstairs with the coat check, while the men and celebs partied upstairs. Boyfriends and parents would show up to try and get us out. But we had our own perfect world. And we looked terrific!”

Lois tells me that whenever she’d come home from college, while she was still living with her parents, she always left the house with two outfits. The one that didn’t betray her secret life and the one she always kept in the trunk of her car. (A used white ’61 T Bird convertible with red leather interior, by the way. No wonder she and Lesley fell in love!) “I’d stop and dress in a diner, changing into my black chinos to look more gay. But Lesley had to go completely cloaked. For her, as a public person, it was a different experience. There were many myths about her that the record company kept afloat, because they wanted to promote a certain picture of her life. She had a lot of fear, but a lot of courage, being on her own since the age of 16sixteen.”

I ask Lois if there’s a particular song of Lesley’s that holds special meaning for her. She answers “Out Here on My Own,” which was nominated for an Academy Award for the movie Fame. A lyric Lesley too often lived. And “We Just Can’t Walk Through Life,” which she wrote with Gloria Nissenson. For Lois, the songs are about “how you have to take responsibility. Everything is our problem. Charity is a negative word. True generosity is when you give what you need. It’s not your overflow. Action and responsibility. That was our life together. Lesley got letters from young people that broke her heart and frightened her, begging her to take them away form abusive homes, poverty, illness. All these requests from kids who thought because she had a hit record she could solve their problems. And she answered every one of them. It took a lot out of her, but it made her responsible. Her fame wasn’t all joy, but she realized she had a responsibility. The year before she passed, we did a gig on a ship. A rock and roll tour. One day a week, Lesley signed autographs and gave away her records. I saw all kinds of people telling her their life story, like she had magic, or healing power. For eight hours straight, signing and talking to people.”

“Last New Year’s Day, we had been to a party with friends. Lesley was radiant. She never looked better. She was happy, which was rare for her. She’d been having back pain. The next day, we decided she better go to the doctor, because this pain was unusual.” —Lois Sasson

“Being stereotyped as a certain type of singer got her down. Not being accepted when she sang something other. Finally she found a new agent, who ‘got’ it. Wayne Gmitter knew how to handle her large talents. He had recently gotten her 27 new bookings. And that was just the beginning.”

Except that it came too late. Lesley would not live long enough to perform at any of them.

After such an enduring relationship, I want to know what held them together.

“Listening. And being present. Making space. Forgiveness. Sacrifice. You sacrifice a mood, a story. Having friends. And our own friendship with each other. I was more social. Lesley wasn’t, because her life was filled with people. She hated to get dressed up. We were T-shirt and jeans girls. We were a committed couple in every sense of the word.”

I pet Billie, who’s sitting in Lois’s lap. I swear she knows who we’re talking about. “And dogs?”

“Dogs did help. They’re an extension. And you’re never angry with your dog.”

I have one more question. This is a hard one. Maybe even unfair. I don’t know how a person has words for it. But Lois will tell me, if she can’t do it. If she can’t find a way. I feel tender toward her, protective of what she’s been willing to share. Even stopping her when it’s something that as a friend I want to hear, but as a writer in the public arena I won’t allow her to reveal.

“How would you like Lesley to be remembered?”

“One of the best wits, one of the funniest women. A discriminating generosity, unlike me. She had to protect herself. A great talent. But stingy with her gifts, which came from people trying to keep her in a box. She didn’t know she was allowed out of the box. Life is rude. She was about to come out of this box by showing she was a great writer. As a writer, as a storyteller, she was cut off from realizing another part of herself before she died. I wish she’d had time to visit that and express that and let others know about that. I just wish she had felt safer in her persona to the world, so that more people would know who she really was. She never stopped amazing me. I hope I did that for her.”

I’m Lesley Gore and I approve this message.

I hope she does.