The director of Sisterhood” talks LGBTQ film representation of queer women in Asia.

Queer female representation in film is crucial for the cultivation of a more LGBTQ friendly, and accepting, world. While it is important for queer women living in the West, it is sometimes even more so for women living in countries that are yet to embrace queer diversity in such basic ways as communal acknowledgement and anti-discrimination legislation.

Tracy Choi is a lesbian filmmaker from Macau, whose cinematic work has been dedicated to uncovering and celebrating the queer communities and identities that exist in her home country, and around other parts of Asia. We were lucky enough to get to talk to Choi about her new film, Sisterhood, the state of LGBTQ representation and acceptance in Macau, and when social conservatism affects our understanding of our own relationships…

FYI, film spoilers ahead.

“Sisterhood” is about many things, but one of the core themes is how harrowing the effects of unconsummated, latent queerness can be. Sei and Ling’s relationship is incredibly intimate, but it never crosses the threshold. In your mind, what is it that stops them from taking their relationship further? And how is this hesitance to cross the threshold something that all queer viewers can relate to?

The things that stop them from taking their relationship further are very complicated. First of all, it’s because they were in 1990s. At that time, Macau was still a small town and did not usually interact with other international cities.

Also Sei and Ling are not well educated, and they are very hard working, just for making a living. They don’t really notice or know about LGBTQ issues in the other places.

For me, Sei never thinks of their relationship in that way. She just thinks that it’s very comfortable to be with Ling. I think it matters to all queer viewers that no matter how it is defined, it’s just love. No matter whether she knows her identity or not, love won’t change.

The homophobia thing I think is more related to Ling, as she notices it. But for me, Ling doesn’t take their relationship further mainly because she wants Sei to have a “normal” life. For Ling, she can’t see that the opportunity is even open for two girls to make a family.

In revisiting old memories, Sei uncovers the queerness that resides in herself, and the film is framed in a non-linear way, with extended flashbacks throughout. Honoring past memories and formative relationships is crucial to the queer experience. How do the structure and the form of the film add to its queerness?

I think the awakeness of Sei is very important. A non-linear way to tell the story is to let her think of the old time piece by piece.

Sei is incredibly detrimentally effected by her loss of Ling, and the life that they might have had. Sei’s husband has to deal with a lot, but he takes everything that comes with such grace.

Why was it important to you to depict his character as such a gentle soul, rather than as someone who would be angry about his wife’s deception or unhappiness with him?

I discussed with the screenwriter many several times about the husband. We thought that if the husband is a bad guy, that will make it too easy for Sei to escape to somewhere else. Sei would definitely try to go away if he were mean. However, if the husband is so gentle, that makes the point more that she still can’t feel anything for him. The love she felt for Ling will be more special and more real.

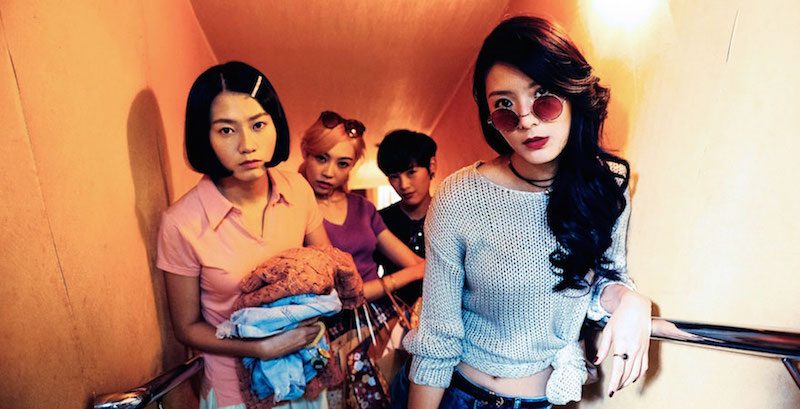

VIA QSFF

Some of the most joyous parts of the film are the scenes in which the young ‘sisters’ at the massage parlor are befriending each other. How significant was it to you to depict not just Sei and Ling’s relationship, but the power of female friendships more generally, too?

This part of female friendship is also very important to me. At the very beginning, when I first think of this story, it’s already a group of friends. It’s because I really know some of the massage girl who work in 1990s. And they really bond together. If some of them got into trouble, the others will help them without any doubt.

Macau itself is another protagonist in the film, and the city goes through character arcs as the women do – from small town atmosphere to holiday city for rich Chinese businessmen. Why was it critical for you to tell Macau’s story, too?

I grow up and born in Macau, so the changing of Macau is really a big deal for me. When I was a kid, Macau was still a small town. Everyone was so close to each other. However when I finished my college overseas and came back to Macau, I suddenly found that the Macau I knew was missing. I couldn’t find the old memory any more. So when we developed the story, I wanted to add this part in it.

Also the D.O.P. of the film is my friend from high school. We grew up together and went abroad to study film together. We tried to film some differences in Macau and tried to show it to the audience.

In the Wikipedia entry for LGBTIQ life in Macau, another film of yours, “I’m Here” is mentioned as one of the only visible LGBTIQ creative productions to have come out of Macau. Do you feel that you carry a heavy responsibility for the LGBTQI people of Macau?

I don’t think it’s a heavy responsibility. I think in Macau, our progress on LGBTQ issues is still very slow.

In your mind, how does queer, and especially queer female, representation in film and the arts, contribute to making the world a more accepting and diverse place?

It’s very important that we show some queer people, especially women, in the film. I think in the other side of the world, people are already doing a lot of things to make it happen. There’s a lot of films about queer people, and even TV shows have got more and more queer characters. But in Asia, the queer character is still missing. Young kids growing up in Asia find it hard to find someone that they can look up to in film and or television. And people still have a lot misunderstandings about people in the LGBTQ group. I think the image of queer characters needs to show up more often.

.jpg)