Why lesbian spaces are disappearing, and what can be done to preserve lesbian history?

In the past two years alone, many cities have seen their last or only lesbian bar close up shop forever. If you can believe it, London, England, only had one, Candy Bar, and it closed late last year. At the end of last summer, Philadelphia lost its well-known, multi-floor bar, Sisters, after losing the less well-known Roy’s Comfort Zone the year previous. And early this year it was announced that The Palms, the nearly 50-year-old bar in West Hollywood, was closing. More last call stories stretch from Portland, Oregon, to Houston, Texas, to Chicago, Illinois. And yet, Oklahoma City keeps two lesbian bars up and running.

Why is it that so many bars are closing, while a few have managed to hang on? And what are the future of other spaces where lesbians have frequently flocked, like feminist bookstores, art galleries, music festivals, women’s colleges, and long-standing institutions like the Lesbian Herstory Archives or the WOW Café Theater?

There aren’t clear-cut or easy answers to the question of why so many spaces are changing or closing. Part of it is definitely economic, as it was for the nearly 90 feminist bookstores in the U.S. that have closed in the past 20 years. In part it relates to political changes. As legislation gradually shifts to reduce LGBT discrimination around things like marriage or employment, it may be that many now feel more integrated into the larger culture and don’t see as much need for separate space or political activism. But for others, marriage wasn’t a goal and blending in was never something they wanted.

A more complicated change appears to be happening at a generational level. For some people, many of whom are under 40, there’s been a shift toward queer identities and politics that are born of a belief that gender and sexuality operate on a spectrum that doesn’t necessarily fit into male/female or straight/gay/bi paradigms. Others, still, prefer and believe in the need to create spaces that are more inclusive. Race, class, and ability can also play a big role for many people in choosing when and where to gather, both for those who identify as lesbian and those who identify otherwise.

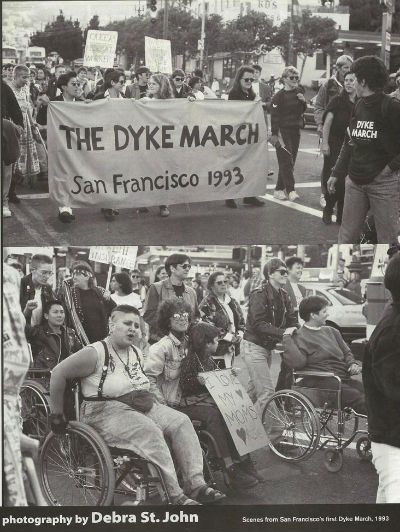

Queer sensibilities and inclusive communities seem to have extended out from the activism of people fighting misogyny, homophobia, and racism in the 1960s, ’70s, and ’80s, including lesbians like Audre Lorde, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Adrienne Rich, among countless others individuals and collectives.

At the same time many others are still drawn to and feel a strong need for specifically lesbian spaces. A number of separatist communities or “wimmin’s lands” remain in the U.S., and beyond separatism, I’ve spoken with lesbians from their 20s into their 70s who worry that inclusion often just ends up meaning that men, particularly white men, end up in charge or doing most of the talking.

So what spaces are there left for lesbians and queer women?

What new spaces are being created? And are there ways to resolve some of the tensions between those who feel that their history and culture is being erased yet again and those who feel they are following in the footsteps of the lesbians who came before them by continuing to push boundaries around gender and sexuality?

These are some of the questions I’ll be looking at in a documentary project I began shooting earlier this year titled The Unknown Play Project. For the documentary I’ll be traveling with a small crew to a handful of different cities across the U.S. to create portraits of some of the spaces that remain and also some that have just begun. To learn more about the project and where lesbian community exists today, visit unknownplayproject.org and please support the project if you can.